For the original article by Jefferson Puff in Portuguese published by BBC Brasil click here.

“In the favela you can’t kiss or walk holding hands. Gays, lesbians and transexuals living in favelas have not benefited from the advances that LGBT people have been seeing across the country. We’re not fighting to be able to adopt children. We are still fighting to survive.”

This was the response given by Gilmara Cunha, a transexual activist based in Complexo da Maré in Rio’s North Zone, when questioned on the differences between being LGBT in the formal city (“the asphalt”) of the South Zone and in favelas.

“There [in formal neighborhoods] they can report prejudice or aggressions and there’s even a chance of the aggressor being punished. That doesn’t happen here. We’re in a lawless land. Our reality is a different one, the risks are different,” says the 31-year-old Rio resident, who in December 2015 became the first transexual to receive the Tiradentes Medal, the most prestigious title in Rio de Janeiro, awarded by the State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) for her services to the community.

Speaking in session, State Representative Flávio Serafini said that the medal represented recognition of the activist’s work. “Gilmara gives a voice to the LGBT population in favelas, which is such a hidden one. And she demands actions and respect for this population from the different spheres of the public sector,” said Serafini.

In an interview with BBC Brasil, Cunha spoke a little about her personal history, which mixes both activism and the maturing of LGBT issues in favelas. Born in Complexo do Alemão and resident of Complexo da Maré since the age of six, she was an altar boy and spent her adolescence in a Catholic church fraternity in Marília, in the State of São Paulo, until coming out as homosexual and later as transexual.

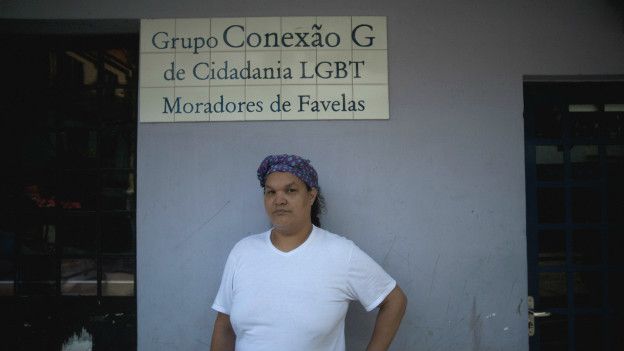

Gilmara began gaining visibility in 2006 as part of Conexão G, the first NGO founded for the LGBT cause in Brazil’s favelas. Today she is a national youth advisor, participates in state and municipal bodies and is often invited to speak at public panel discussions and to give speeches across the country and even in the USA and Argentina.

In Maré she has organized six LGBT pride events, which have brought together up to 30,000 people. She is constantly active, supporting initiatives with different groups founded in different favelas across Rio and has already received a prize from the Ministry of Health for her work.

For Gilmara, who describes herself as “poor, black, from the favela, and proud of it,” LGBT people in favelas are “far from being included” by public policies as well as “being remembered” by campaigns and anti-homophobia centers or health-promotion centers.

“Gays and lesbians in favelas are not the priority. And transvestites and transexuals are even less of a priority,” she says.

Excerpts from Gilmara’s interview with BBC Brasil:

“My family was always a very humble one, and I have one brother and one sister. When I was about 13 years old I started to become aware of my homosexuality, which led me towards the Catholic Church since I thought my feelings were to do with sin.

I was born in a chauvinist, heteronormative environment, and when I started to show characteristics considered to be more feminine, I kept hearing that I need to ‘be a man.’ The Church was a form of trying to crush this desire that was somehow starting to appear in me, but I didn’t know from where or why it was appearing.

I was an altar boy in a church in Maré and later moved to the Toca de Assis Fraternity where I stayed until the age of 21 when I quit studying to be a monk and returned to the favela.

Some two months later I took part in a project about gender equality and slowly started to understand better who I was and what homosexuality was.

Bit by bit the idea emerged to set up a group inside the Maré favela to work on reducing homophobia, because we know that even though it is never going to disappear altogether, we can reduce it through campaigning and actions that get through to people in their daily lives.

The NGO Conexão G was founded in 2008 with that idea in mind. I founded it along with five other young gay people. That same year I went to give a speech in the USA and I was offered resources to fund a degree in psychology here in Rio. I have two years of my degree left to go. I stopped my studies to focus on the NGO.

Conexão G was the first favela-based LGBT group in Brazil. Now more groups are emerging and I’m pleased to know that my choice to prioritize the NGO over my studies worked out well. It’s gratifying to see the results and to see that we are motivating other people.

At the beginning we weren’t really aware that we were getting involved in politics. We suffered prejudice and daily aggressions. People cursed us, threw onions and stones at us. We realized that we needed to do something with concrete results as quickly as possible, in order to create a better quality of life for this population living in favelas.

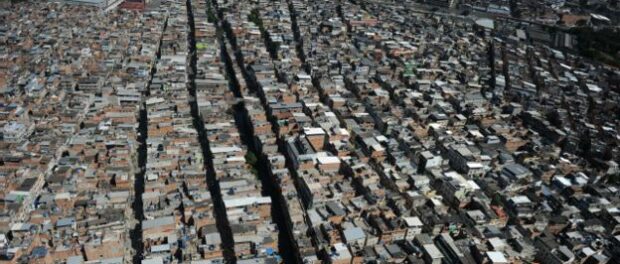

Given that people already consider Rio to be a divided city, with favela residents worse off, as gays living in the favela we were even more vulnerable. We were poor, from the favela and homosexual. There were leisure spaces in the community, for example, that we couldn’t go to, because people would mock us and laugh at us.

In the beginning it was really difficult. It was really bad.

There are lots of issues in favelas and one of them is to do with the power of the drug gangs. Power in the favela is chauvinist, sexist, homophobic and transphobic. I had to put my head on the line many times in order for our work to gain some credibility. We also worked alongside another established NGO in order to earn respect.

Another factor is evangelical churches. The absence of the State in favelas has created favorable conditions for the proliferation of churches, which have definitely contributed to homophobia and to violence against LGBT people in favelas.

But slowly things started to change and we began to win over families. Our aim was quite simply to break down prejudices, so we would do shows and performances in the middle of the street, not in closed spaces. We were breaking down people’s fears that all the children would become transvestites or homosexual if they came into contact with us.

We conquered people through our joyfulness. Even though our joy was a facade, because we didn’t feel very joyful. We were using a strategy to achieve respectability within the community.

Did it work? Obviously it did, you only need to see that today we can manage to organize a LGBT pride march with a mobile music stage and 30,000 people inside the favela to see that. It worked so well that I’d say it was the perfect recipe for success.

We started from a reality where we defined ourselves with the phrase “let me exist,” and now I think this is being achieved, despite a lot of challenges remaining. Today the motto that defines us is “I am gay, I am lesbian, I am a transvestite, but I am equal to you and I demand respect.”

Our fight has expanded and we have been calling attention to the lack of public policies for LGBT people in favelas.

Our governmental bodies don’t mobilize when people talk about homophobia in favelas. Today, if something happens in Ipanema or Leblon [in Rio’s South Zone], the reaction is different because those neighborhoods are a kind of ‘showcase.’ In the case of people in favelas stereotypes of marginalization and violence dominate perceptions of residents, whether they are straight or gay.

Gay people in favelas are still very much forgotten about on all sides. Anti homophobia campaigns and groups engage a lot with the middle class but very little with the favelas.

To go inside the Center for the Prevention of Homophobia in downtown Rio you need to be wearing a certain type of clothing and have the right documents. Favela residents can find it harder to access this center to file a statement or complaint and there are no such centers inside the favela.

Have there been advances in the LBGT cause in the country as a whole? Of course, but we [favela residents] have not enjoyed these advances. Civil partnerships, gay marriage, adoption rights. In the favela we are still fighting for something much more basic: for our lives. The preservation of life.

Walking holding hands and kissing? I would say that this is still almost impossible for an LGBT person inside the favela. It could happen, but there will certainly be repression, which could take the form of a bad look or a curse. Personally I don’t walk hand-in-hand with my husband.

And of course for transvestites and transexuals prejudice is always worse than against gays and lesbians. You can now see transvestites as deans of universities, holding important positions, but even so we are still simply within the sphere of showing we are here and we exist. We’re still not seeing a real increase in rights and more respectability.

As we are a very vulnerable population, many transexuals are killed in Brazil. Deep down, people think that the killing of a transvestite won’t come to anything, maybe because of this negative stereotype that exists of transvestites as attackers, robbers, marginal people. In reality, society approves of people who kill transvestites. Transexuals are being wiped out and society doesn’t care.

What do I think about the medal and the future? For me this medal represents the fact that it’s no longer acceptable to ignore LGBT people from favelas.

I always present myself as a favela resident. I go to bed and wake up with the word favela in my mouth. I consider myself to live in a favela, not a community, because community is an academic term. Calling where I live a community and not a favela will not minimize what my life is like in the favela, so I prefer to call myself a favela resident. Poor, black, from the favela, and proud of it.

My dream is to create a community center in Complexo da Maré, offering all kinds of activities, advice, services and healthcare, and with a space to report homophobia. With training for staff too, so we can create a network. I’m working towards this goal.

What about my future? I got married four years ago and my family, the first people to repress me, now accepts me to the point that we live together. It was difficult in the beginning, but now we live side by side, me, my family and my husband, and we have created a healthy environment for us all.”