On April 24, a public meeting was held at the Rio Public Defenders Office with the title “Houses Invaded, Lives Violated and Other Police Abuses in Complexo do Alemão.” The meeting focused on police invasions of residents’ houses–to be used as police bases–and went on to cover the larger debate around arbitrary and violent police actions experienced in the favela.

Given the current tensions in the favela, the atmosphere of the meeting was highly intense, emotionally charged and at times combative, despite efforts of the panel to moderate. The panel included representatives from the Public Defenders’ Office, the Human Rights Committee of the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly, the Public Security and Health Secretariats and leaders of the Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), as well as representatives from social movements within Complexo do Alemão. The initial aim of the meeting was a conciliatory one–to open up a channel of dialogue between residents and police. State representative Marcelo Freixo, in his role as president of the Rio Legislative Assembly’s Human Rights Commission, stated that “We need to stop wanting to know which side [the residents or the police] has the higher body count. There’s no winner.”

People shouted from the audience in response to Freixo’s attempt to create a mutual identification among both police and residents as equal victims of the same failed public security policies: “But there is a side A and a side B!” Incidentally there was a spatial division in the room: the uniformed policemen present, numbering around 30, sat together on one side while residents, carrying placards, occupied the other half of the room.

“The police talk about the war on drugs, but really it’s a war on residents. Stray bullets only hit residents. The police enter the favela and use people’s houses as bases. They kicked an elderly couple out of their house violently, peed on a resident’s television, stole a child’s yoghurt while pointing a gun at her and saying ‘If you don’t shut up, I’ll make you shut you up.’ I’m not defending criminals, but no drug dealer has ever thrown people out of their houses like this,” said Cleonice Madalena, Alemão resident and volunteer for the FavelArte project. Pastor Jorge Felix spoke about having to move to a different favela: “My house became a strategic point for the Military Police, which uses my roof space as a place for handing over shifts. They claim that these are war conditions and they have permission from their superiors to be there.”

From the panel, Lieutenant Colonel Marcos Borges, UPP sub-captain, tried to justify the invasion of houses in the Praça do Samba area as a temporary measure, given the lack of a military base for police to use to protect themselves.

“A house in Complexo do Alemão has to be respected just as much as a house in Leblon [in Rio’s wealthy South Zone],” said Freixo.

The establishment of UPP bases in Alemão has caused controversy before: previous locations used as UPP bases have included part of the grounds of a school and a sports ground. These actions have restricted children’s access to education and leisure, illustrating the hierarchal nature of public policies created by the State: such basic services are subordinate to police needs.

Some of the occupied houses in Alemão have been occupied since January, but the recent history of terror in Alemão can be traced back to the occupations of 2010, when the armed forces invaded the favela complex and the Military Police hoisted a flag at the top of the cable car network as a symbol of a takeover of territory. Panelist Raull Santiago, activist from the collective Juntos pelo Complexo (Together for the Complexo) said that “These operations function through the logic of fear. In 2010 they came with a different kind of discourse and repeated the mistake–or maybe it was intentional–and reaffirmed policing as the only type of public policy that reaches the favela. Police were sent to prevent the reoccupation of the little Skol favela, but today the police occupy three homes at the top of Alvorada and nobody talks about [the right to] property, because property belonging to poor people is worth nothing.”

Ever since UPPs were first installed in Complexo do Alemão, the same story has been repeating itself: in recent weeks, just as in 2014 and 2015, the reality for residents has consisted of a high number of deaths resulting from police operations, followed by protests for peace and mobilization on social networks, as well as events like this public meeting, which recommended the end of the UPP presence in the community. The meeting ended with a lot of tension and the exchanging of accusations. This often repeated story does however go back a long way: as shown by a video at the beginning of the public meeting, this is the fruit of a way of thinking of security policy as a war between victims and villains. The video showed a timeline of police operations in the favela, reminding those present of the policies that predominated in the 1990s, like awarding bonuses to police for engaging in shootouts that resulted in deaths and continuing up to the 2010 occupation, reinforcing an idea that was repeated by several residents during the public meeting: “The State normalizes death,” especially the deaths of poor, black people and those living on the city’s periphery.

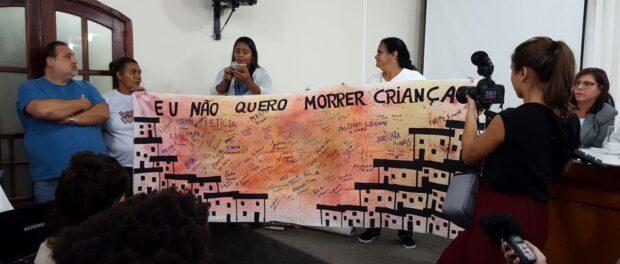

“Rather than getting the police out of our homes, what we want most is to save people’s lives,” said Alan Brum, Alemão resident and activist from the NGO Raízes em Movimento (Roots in Movement). In this vein, the meeting went on to remember some of those who have lost their lives or their liberty during the ongoing conflict in Alemão. Lots of the residents, after taking the mic, began by shouting “Eduardo, present!” or “Freedom for Rafael Braga,” as a way of honoring such people. Terezinha, the mother of Eduardo [the ten-year-old boy shot by police in 2015], used her opportunity to speak to reiterate the community’s lack of confidence in the police.

Dalva, another mother whose son was killed by police in Borel favela, said that the criminalization of the favela means that “the war is not against drugs, but against people.” Raull spoke of other police killings: “Bruno died when he was shot in his home, Gustavo when he was going to work. Today marks one year since the funeral of Shrek, the moto-taxi driver. The police opened fire on him before asking questions, a typical police response.”

The absence of Rio;s governor or a representative of the State government’s office–responsible for public security policies and the management of the Military Police–did not go unnoticed. Other notable absences included representatives from the secretariats of education and culture–entities which are essential for thinking of a human and integrated approach to public policy in favelas. Another notable absence was that of Rio Mayor Marcelo Crivella, since some of the actions of the mayor’s office, such as recently proposed infrastructure projects, could mitigate or reinforce a feeling of insecurity. “I wish Crivella could show up here for me to ask him if, as well as bullet-proofing schools, he’s also going to bullet-proof our houses or even our children, since they are fired on while on their way to school. This is a cheap form of demagogy,” Cleonice said.

The main source of disagreement during the meeting started when a policeman asked to take the mic to refute some residents’ accusations of a genocidal police force. “In a war, we need to choose a side,” he said, defending the idea that, since residents are learning how to film police actions (a right guaranteed by the law) they should also film drug dealers’ action. His comment was met with hisses from the audience, with some audience members shouting that they weren’t there to do the job of the police. The policeman’s commentary also showed a certain insensitivity on his part, since he was essentially asking residents to place their safety and physical integrity at risk by proposing they position themselves face to face with drug traffickers. Filming the police and filming traffickers shouldn’t be seen as equal activities, since filming police activity should not be seen as a risk if residents are working within the law and the police have a mandate to protect citizens. Accusations thrown around during the meeting included “assassins” [for the police] and “accomplices of traffickers” [for the residents].

When members of the police left the room, this was also followed by the media (heavily present for the meeting) making their exit too.

At a moment when residents were taking the mic to tell their experiences, all cameras and microphones were turned to Captain Zuma, head of the Alemão UPP, who was showing photos of armed traffickers, while insisting that only one previously-abandoned house had been occupied by police, even though the Public Defenders’ Office has identified at least five occupied houses. In an attempt to justify the occupation, Zuma claimed that in the Praça do Samba area “there was a large marijuana selling point” and several abandoned houses, riddled with bullets. He claimed to have put his career at risk to protect the life of his colleagues, who were being attacked by traffickers and avoided answering a question repeated by lots residents in attendance: “Were you acting within the law?”

At a moment when residents were taking the mic to tell their experiences, all cameras and microphones were turned to Captain Zuma, head of the Alemão UPP, who was showing photos of armed traffickers, while insisting that only one previously-abandoned house had been occupied by police, even though the Public Defenders’ Office has identified at least five occupied houses. In an attempt to justify the occupation, Zuma claimed that in the Praça do Samba area “there was a large marijuana selling point” and several abandoned houses, riddled with bullets. He claimed to have put his career at risk to protect the life of his colleagues, who were being attacked by traffickers and avoided answering a question repeated by lots residents in attendance: “Were you acting within the law?”

The residents recount a different version of events, vouched for by Dr. Lívia Casseres, representative of the Public Defenders’ office on the panel. She told of how in January the Defense Nucleus of the Public Defenders’ Office was sought out by families that claimed to have had padlocks to their homes broken and accused the police of constantly using their roof space. Aerial images and the presence of household appliances suggest that the houses in the area were not lying abandoned and, even if they were, Brazilian law does not allow them to be occupied. At the end of the public meeting, the Public Defenders’ Office recommended that the police stop the occupation and damages be paid to victims, including for damaged electrical appliances.

Residents argued that the sub-captain of the UPPs in Alemão be arrested, since he had admitted that the house occupations took place–which is against the law. Lieutenant Colonel Marcos said that the UPPs’ aim to “promote peace and preserve life” had to be abandoned. “The rise of criminality required a change in attitude,” he said. Marcos agreed with Zuma’s claim that the occupation of residents’ houses was to protect the police. The police are already preparing to leave the houses but–surprisingly, considering the way they took over the houses in the first place–this needs to be done in a planned way. “We were going to leave the houses today, but it rained a lot over the weekend,” was the justification given at the meeting.

Marcos said that the police force have a committee to reevaluate the future of UPPs and to deal with police abuses. On hearing this Mariluce Mariá, coordinator of FavelArte, retorted “Is it in this committee that you lot decide if we live or die, colonel? If so let me know where this committee takes place.”

The idea that residents can be expected to denounce police actions to the police themselves is a bit illogical, given the lack of confidence the community has in the police to carry out an investigation, or due to fear that denunciation would lead to police retaliation. One of the residents on the line-up to speak, whose house had been occupied by the police, backed out of speaking, due to the police presence at the meeting. Leonardo Souza, an Alemão resident and activist in Ocupa Alemão, questioned the police’s presence at the public meeting: “For me, the presence of the police in a meeting where the police is being accused of breaking the law only leads to one thing: coercion of residents.” In his opinion, the public meeting should not serve a conciliatory function, but should instead provide a space for making allegations: “Weapons and drugs come into Alemão because of police corruption.”

Fransérgio Goulart, activist from the Youth Forum said that nothing had happened after other public meetings of a similar nature in 2015 and 2016. “The only change is that the number of deaths is now higher,” Raull added. “These meetings are not resolving anything, but there is one positive aspect which is that it provides a therapeutic space. The community comes here and yells and shouts and the police have to sit quietly and listen to us. You’re not going to kill me here,” said Fransérgio.

While the public meeting was taking place, the Facebook page of the Coletivo Papo Reto (Straight Talk Collective) denounced the presence of Military Police and BOPE (Special Operations Battalion) in Alemão–alleging that they had closed one of the main streets in Alvorada in order to construct a police base. The ensuing police operation resulted in two police officers being shot, one resident being killed and at least one house occupied by police. The resident who was killed, 13-year-old Paulo Henrique, is another name to add to the list of recent victims, which includes 17-year-old Gustavo and 22-year-old Bruno, killed on Friday April 21, and Dona Bernadete, 68 years old, who fell from her roof, frightened by a shootout.

On the day after the public meeting, residents organized a march with the theme of “Favela Lives Matter.” On the same day, more than 4,000 children went without school due to a police operation, that killed another young resident, Felipe Farias. On Thursday April 27, shootouts on the street caused teachers to run to bring children inside school buildings while they were on their way to school–an event which backs up a criticism made during the public meeting that many police operations take place at the same time as children are arriving at and leaving school.

Just after the public meeting, Mariluce asked her friends on Facebook “If you could, would you leave the community?“–to which the vast majority of commenters replied explaining their affection for their community, while at the same time saying they’d either already left or they would leave if they had the opportunity, due to the difficulties they experienced from the feeling of insecurity and a lack of trust in institutions. Some people disagreed. For example, Elilton Moreira commented saying “I will never give in to this failed state with its murderous and corrupt police.”

At the end of the public meeting, some residents said they were scared to leave, given the police presence at the entrance of the building and at home too, since they’d been hearing via social media that shootouts were taking place at that moment in Alemão.

Some of the recommendations made by residents during the meeting included: the end of police operations during periods where lots of people are on the street; the end of the use of heavily armored vehicles and arbitrary searches of residents; house occupations only when preceded by a search warrant; the removal of police officers under investigation of police killings alleged to be in self-defense; the construction of a memorial for the victims of police violence and the end of judicial complicity with police violence.

Despite some doubts about the meeting’s conciliatory aims, it was effective in attracting the attention of large media organizations to police abuses taking place in Alemão, and succeeded in getting a public (and therefore open to scrutiny) promise from the sub-captain of the UPP to remove police from occupied houses before the following Tuesday (a promise that residents alleged had not been honored on Thursday). And on Friday April 28, in a historic ruling, judge Roseli Nalin ruled in favor of the Public Defenders Office’s recommendation that police leave the occupied houses immediately. As well as all this, the public meeting showed the political strength of a group of residents who will not keep quiet in the face of police violence and that gets organized to film, denounce and claim their rights.