On Tuesday, July 4, Mayor Marcelo Crivella, in office since January, made public his proposal for the 2017-2020 Strategic Plan for municipal management, a few days late. There are four major thematic dimensions: Economy, Social, Urban-Environmental, and Governance, covered by 65 strategic initiatives and 101 goals. The Plan is much more robust than the previous government program of candidate Crivella, which had only 50 goals and did not even mention the word “favela,” where at least 23% of the city’s population lives. In the Plan, there are 13 mentions, although it is possible to argue that the definitions used reinforce stigmas, seeing favelas as a problem to be solved, an approach that by its nature limits the potential to find solutions based on the existing assets of these areas. This is the case of the terms “precarious informal settlements” and “poor communities” used in the plan, and the one-sided definition of favela assumed in the Strategic Plan:

“Predominantly residential area, characterized by clandestine occupations and low-income, precarious urban infrastructure and public services, narrow roads and irregular alignment, lack of formal installations and property links and unlicensed buildings, in disagreement with current legal standards. “(Supplementary Law nº 111 of 1/2/2011)

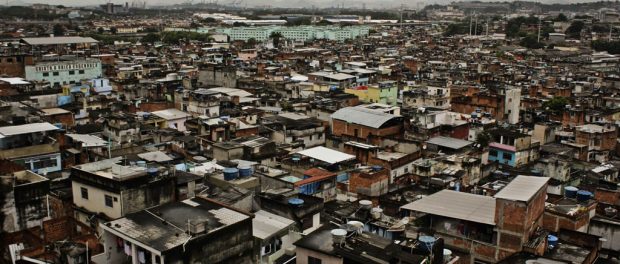

Nevertheless, the Strategic Plan recognizes that the city has “acute differences of income and quality of life within its neighborhoods, divided between the formal city and low-income communities,” whose proximity leads to the rare simultaneous experience of both coexistence and segregation. It also points out that the growth of favelas can be attributed to “a historical absence of policies and financing of low-income housing” and that, over time, there has been a lack of political will to resolve issues such as “land regularization and social and productive integration from the favela to the city.”

The moment now is for citizens, technicians and civil society organizations to discuss the goals set out in the Plan and to contribute to its review over the next three months, on an online platform or at thematic workshops to be announced by City Hall. Next, we seek to bring input to these debates, highlighting some points of the Plan that have direct impacts on favelas, and others in which the impact on favelas was not directly considered.

Favelas in the Strategic Plan

Mentions of Favela territories are concentrated in the Urban-Environmental Theme, especially with regards to the following three strategic initiatives:

More Houses

The plan for “More Houses” will aim to reduce the housing deficit, especially of families with incomes of up to R$1,800 in areas considered at risk or extremely precarious. To this end, the municipality commits to the disposal of municipal land and production of homes, incentivizing programs to build housing of social interest and encourage the contracting of My House My Life housing program units, among others. Specifically, it commits to the implementation of the Port Region‘s Social Interest Housing Plan (including housing units, social rent and land tenure regularization) and to “Produce Housing Units of Public Interest in the Jacarezinho favela.” The criteria for selecting Jacarezinho were not disclosed, nor what it means that they described the housing units as being of “public interest” rather than of “social interest.”

Integrated Territories

“Integrated Territories” will include actions that contribute to the “urban, social, economic and cultural integration of residents of precarious informal settlements in the city,” including “upgrading and implementing infrastructure in precarious settlements,” the development of “studies aimed at the requalification of the communities of Rio das Pedras and Maré,” “urbanistic and land regularization through the approval of Alignment and Allotment Projects and the recognition of stream names in Areas of Special Social Interest (AEIS),” the provision of “digital information, through SIURB, referring to infrastructure projects for initially 50 favelas,” and the “recovery of precarious housing and the rehabilitation of housing complexes,” among others.

Central Rio

“Central Rio” will promote the approval of new housing units in the central area and the occupation or revitalization of empty and underutilized properties to strengthen the housing potential of downtown and alleviate the housing deficit in the rest of the city.

These three strategic initiatives–More Houses, Integrated Territories, and Central Rio–are aligned with the Plan’s following goals regarding favelas:

- M73: Benefit 21 favelas in Areas of Special Social Interest (AEIS), upgrading them by 2020. Its inclusion represents an advance, but raises issues that are not covered in the Plan of how this upgrading will be done. Will it involve the population in its planning and execution? Will it be done through previously studied and existing programs, such as Morar Carioca, or new programs? Will it involve public-private partnerships? What are the criteria for choosing these favelas? How has this number been defined and how many families will be impacted?

- M74: Complete studies for the urban revitalization of Rio das Pedras until 2018. Crivella also announced in the campaign that he would use concessions and public-private partnerships to solve the housing shortage in Rio das Pedras, focusing on verticalization. This strategy has already been adopted by vigilante off-duty police militia speculators who build unlicensed buildings there now. Infrastructure problems go beyond the housing issue, including sanitation problems, which also need to be covered by the study.

- M75: To benefit 100,000 households with upgrading and land regularization (titling) procedures by 2020. Simplifying the debate, the advantages and disadvantages of land titling in favelas includes, on the one hand, access to credit and the possibility of sale in the formal market and, on the other hand, the rise of prohibitive taxation for those who want to remain in the favela and the insertion of the land in the formal housing market, opening space for gentrification. In the specific case of Rio, where titled favelas such as Vila Autódromo can run the same risk of removal as untitled, the title is not synonymous with a guarantee of permanence.

- M76: Ensure that 14,204 dwellings will not be in an area of high geological-geotechnical risk in the Tijuca Massif by 2020. The Plan states that there are 20,664 families in areas at risk of landslides around the Tijuca Massif and in both the Alemão and Penha Complexes, but the goal is restricted to the Tijuca Massif. This goal will be measured by the “cumulative number of houses removed from high-risk areas.” This opens space for two interpretations: homes ceasing to be at risk by carrying out necessary infrastructure works that reduce risks, or the eviction of residents from these areas, which is worrying. Will infrastructure projects be prioritized so as not to disrupt the social fabric of communities by resettlement in remote areas? Or is the risk discourse being appropriated to justify violent removals? It is important to analyze these data better because there is a history of Rio’s geotechnical agency, GEO-Rio, compounding the risks in some favelas apparently to justify forced removal. It is necessary to have a clear action plan, built in a participatory way, and based on both the physical risk and on the strength and importance of the sense of belonging of the residents.

- M77: Build 20,000 Housing Units of Social Interest until December 2020. It is necessary to know the criteria of geographical distribution of these units. It is desirable that they be located in underutilized central areas, promoting mixed use, than in distant and disarticulated locations in terms of transport, as is often the case.

In relation to the Economy section of the Plan, some goals and initiatives speak of the decentralization of employment to the North and West Zones, the training of young people from vulnerable areas and more susceptible to informality and the prioritization of purchases by the municipality of activities carried out in the most vulnerable regions of the city. (Which will be called the Social Free Trade Zone). The Plan also includes an online platform, called the Integrated Community Network, to connect local offers and demands, whose pilot project will be implemented in the Maré communities. In the Urban-Environmental section, the “environmental readjustment of rivers near poor communities,” as part of the Rios Cariocas program, could lead to evictions based on the environmental argument. In addition, one can question the restriction of the program to rivers near “poor communities,” instead of bringing an environmental justification as a criterion.

On the other hand, the Social section of the Plan encompasses issues of health, public safety, education and culture, among others. In the area of health, the expansion of the Family Health Program is foreseen, in addition to the expansion in the number of beds, polyclinics and surgical procedures. For education, the Plan proposes the opening of 40,000 spots in daycare centers, 15,000 in pre-schools and 45% of public school students in full-day educational programs. The plan is still committed to the renovation and reopening of cultural facilities, many of which are located in favelas (such as the Manguinhos Library, closed last year due to lack of funds) despite not foreseeing the creation of new ones.

Favelas left out of the plan

We believe that some points raised in the Plan should have been considered based on the territory in which they would unfold, given their potential impact on favelas. These include but are not limited to the following initiatives:

“Rio de Janeiro a Janeiro”

The “Rio de Janeiro a Janeiro” initiative is aimed at promoting cultural and artistic events, as well as encouraging tourism, but does not mention cultural and touristic activities developed in favelas at any time. These activities generate employment and income within the community, reinforce security and stimulate self-esteem, but by not recognizing these cultural expressions, nor the need to encourage them, the Plan does not provide a guarantee against the barriers imposed against community events by the UPP police command, among others.

Citizen Security / Incentive Policies

The public security initiatives in the Plan make no mention of policies and actions directed at favelas, which are the most lethal areas in the municipality. This could be attributed to the limited performance of Rio’s City Council on the subject due to its non-interference with the state Military Police, but there is a goal aimed at reducing non-violent crimes in the beachfront neighborhoods, raising the question of what the goals would be for the rest of the city, non-touristy areas that are less well-off.

In addition, these initiatives deal with the requalification of the Municipal Guard and the increase of the proximity policing program. The work of the Guard will be based on “community policing and ostensive surveillance,” through more “proactive” actions, which raises concerns as to who will be protected and against whom, especially given the current intention of City Hall to arm the Municipal Guards. Thus, two important questions arise: what will be the areas of the city that will have this policing, and against whom will this ostensive surveillance be carried out?

“Payment of bonuses to state and municipal public security agents is also planned,” which would include the Military Police, even though they are not within the scope of the city government, but rather a State body. Encouraging so-called ostensive surveillance and paying for undefined “crime reduction” targets risks leading to the authorization of already common practices of aggressive and racist action by security forces.

Related goals:

- M43: Reduce non-violent crime rates in the beachfront neighborhoods of Rio de Janeiro by 50%, by 2020.

- M44: Assign 80% of on-duty Municipal Guards to community policing and ostensive city surveillance on a daily basis through 2020.

- M46: Create the Special Fund for Public Order (FEOP), by 2018, adding to Rio’s Proximity Guard Policy.

Human Rights

The initiative aims to create human rights centers in each of the city’s five Planning Areas (APs), “to promote permanent dialogue on human rights, providing an analysis of the local reality in light of the themes advocated.” Despite the territorial dimension mentioned, there is a lack of a more specific mention of favelas, both in terms of the territories served by these human rights centers and the sorts of violations they will address. How can one speak about human rights in Rio de Janeiro without mentioning violations that include evictions, home invasions, false imprisonment, disproportionate and skewed police violence?

Expansion of Sanitation

The initiative focuses only on the expansion of sanitation in AP4 (Barra da Tijuca and Jacarepaguá), which will be done through private concessions, not taking into account that sanitation infrastructure is the number one demand in favela territories across the city.

And now?

In terms of governance, the Plan states that it aims to promote transparency and participation of the population in public policies, seeking decentralized governance closer to the population, in order to reduce regional inequalities. To this end, the City government has committed to publish the dates of the workshops for consultation about the Plan, as well as an online platform where public contributions can be sent. Once consolidated, the City commits itself to providing semi-annual and annual reports to evaluate the progress of the Plan, as well as monitoring and social control platforms.

Now it is up to the population to assess the adequacy of the goals set and what is missing from the Plan, and to propose changes or additions and, later, the monitoring of the targets and of their implementation. We will post the City’s agenda of public consultations and the channels available for participation as soon as they have been scheduled by the City.