The end and beginning of a new year, besides being a time for festivities, is also the moment in which many mothers and fathers in Brazil pay the most attention to their children’s education, whether congratulating them if they have passed the school year, without worry about their learning process, or worrying because their child has failed. Children fail for different reasons: too many days missed, low grades or other school performance issues. This is a very common scenario in public schools in low-income neighborhoods. In the Manguinhos favela, parents, students, and teachers are all too familiar with this drama.

To better understand the situation, I, Edilano Cavalcante, coordinator of the community communication agency Fala Manguinhos! (Speak Up Manguinhos!), interviewed the principal of a state school that is located in the neighborhood.

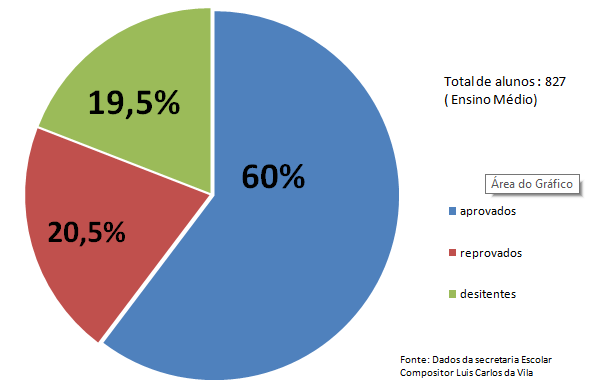

I visited the Composer Luiz Carlos da Vila State School to talk to Michelle Nascimento, who has been the school’s principal for one year. We talked about a variety of subjects, from student learning to public education policies and the parent-school relationship, and we were given access to data on passes, fails, and dropouts for the 2017 school year for high school students. The data are worrying.

The Composer Luiz Carlos da Vila State School is located in the Praça do Depósito de Suprimentos do Exército (Army Supply Depot Plaza—DESUP), or ‘Praça da Cidadania’ (Citizenship Plaza), as it was baptized by former governor Sérgio Cabral during the years of the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC). In a visit to the neighborhood, Sérgio Cabral and former president Lula promised residents that the high school would be a model of quality education, culture, and public participation, as part of a public-private partnership between the State and Odebrecht.

In the beginning the school received all the support promised and was viewed by Manguinhos residents as a jewel, but within a short time investments were reduced and the activities that made the school stand out were put on hold, to the point at which the teachers went on strike due to unpaid wages and a lack of resources. During the strike, the students had to occupy the school for more than a month and demand that the Secretary of Education resume the supply of resources in order to keep the school functioning. During this process of closure and struggle, the school suffered various blows to its infrastructure, with even the electrical wiring and windows, among other items, being stolen.

It was in this period of resistance on the part of the students, when no one wanted to take responsibility for the management of the school, that Nascimento decided to come to Manguinhos to fight with the students to keep the school open and guarantee their right to a basic education.

EC: What has your experience been like in your first year leading the school?

Nascimento: I consider it a good year, productive with a lot of progress. Despite all the incidents of desecration, we have been able to restore the school with the help of the residents and local partners. One example is the school library, which will reopen at the beginning of 2018. Another is our sports field which is in the process of being repaired, an important environment for activities and recreation, as well as other important spaces for our school.

In terms of management, the staff are very good, however the team is incomplete. Previously we did not have all the teachers—now we do, but we’re still lacking administration professionals and we don’t have educational counselors, among other professionals. And even with a great team, we’re all performing multiple roles at the same time and obviously can’t handle it. This ends up overwhelming everyone to the point where people need to take medical leave a few times a year.

EC: In terms of the end of the 2017 school year, what were the pass, fail, and dropout rates for the high school students? In your opinion, what explains the results?

Nascimento: The numbers are troubling and it’s very important that everyone understands the gravity of what this means both now and in the long term. Let’s look at them:

- Passed = 60% (500 of 827 total)

- Failed = 20.5% (169 of 827 total)

- Dropped out = 19% (158 of 827 total)

Broken down by high school grade level, the numbers are as follows:

- 1st year – 41% passed (114 of 280 students), 35% failed (99 or 280), and 24% dropped out (67 of 280)

- 2nd year – 65% passed (100 of 154 students), 17.5% failed (27 of 154), and 17.5% dropped out (27 of 154)

- 3rd year – 91% passed (119 of 131 students), 6% failed (8 of 131), and 3% dropped out (4 of 131)

It is important to emphasize that our greatest concern is with the 1st year of high school, since this reflects the problems in primary education, reflecting a structural problem in terms of very poor quality education in Brazil. There are many causes, but the worst of all is the archaic and outdated approach with which the federal government, through the Ministry of Education (MEC), continues to guide education in Brazil. When it comes to public education, this approach is marked by neglect, low investment, and disrespect for teachers, managers, students, and their families.

EC: Why is the school dropout rate so high in high school? How does this affect family life?

Nascimento: The dropout issue has always been and continues to be a problem in high school, first because up to the 9th grade, parents are required by law to keep their children in school, and the Conselho Tutelar (equivalent to Child Protective Services) has a careful monitoring process to ensure this happens. When students enter high school, however, the Conselho Tutelar no longer monitors these young people with the same attention. Another factor is the need to work to supplement family income, especially among boys. Many leave school to take up informal work with long hours and tiring work. And another large portion of the dropouts occurs because of a genuine lack of interest in going to school, because the students do not see it as advantageous to be trapped in classrooms in an outdated learning environment. They prefer to leave their house and hang out in the squares or in the schoolyard with other young people.

EC: What public policies are needed so that schools are seen as attractive sites for collective learning? What is the State currently doing?

Nascimento: This question of attractiveness is something that has been a matter of debate for a long time, with efforts to change the way students are ‘educated,’ with new methodologies that are better connected to the current world and with new perspectives, instead of this 18th century style with chairs in rows and a ‘teacher who knows everything’ and a ‘student who knows nothing.’

In the last six years a new approach towards high school has been growing based on the combination of high school and technical colleges, which gave school and the aim of education a new look. But with this crisis and Rio’s public coffers being robbed, the resources were gone before we could do a mid-term analysis. This most recent government has increasingly reduced the resources for education and once more this shortage falls most heavily on those who need the resources most.

EC: What is the relationship between parents and the school and how does this impact student learning?

Nascimento: The relationship of dialogue with parents is very complicated, especially when it comes to high school students. Most of the time, parents don’t even come to the school to find out if their son or daughter is attending or not, and when we contact them, most of them say they are unable to interfere with their children’s choices, they say that they don’t have time to take care of the issue and that they can’t force their children to go to school. We also can’t rely on the Conselho Tutelar, as we know that it doesn’t have the capacity to respond to needs of high schools. So the student leaves school and we can’t do anything, because it is a systematic problem, the result of multiple factors that neither I, as principal, nor the teachers can fix, although every day we strive to solve this problem.

As we have seen, the Composer Luiz Carlos da Vila State School is no longer a model high school for quality teaching. Instead, it has become an example of public neglect and disrespect for the education of children and young people who need public education. Unfortunately, this reality extends beyond schools in Manguinhos. It is something that permeates the entire history of public education in Brazil.

These dropout numbers are tantamount to a large share of poor and marginalized Brazilians that the country makes a point of maintaining in their historical, political, social, and cultural context. For how long will constitutional rights be nothing more than beautiful words written in a book for the majority of Brazil’s marginalized and peripheral population?

This article was written by Edilano Cavalcante and produced in partnership between RioOnWatch and Fala Manguinhos! (Speak Up Manguinhos!). Cavalcante is coordinator of Fala Manguinhos!, a community communication initiative produced by and for Manguinhos, and set up to defend human and environmental rights in the favela, and to promote citizenship and health with the direct participation of residents in the decisions that involve the Community Communication Agency of Manguinhos, from the meetings of the communication group and the Community Council. Follow Fala Manguinhos on Facebook here.