For the original article in Portuguese by Bruno Alfano published by Extra click here.

“The reopening [of the library] is politics, we know this. It’s an election year after all. But we have the right to culture, reading, and education. We’re not going to trade this library reopening for votes. They, the state government, are doing no more than their obligation.” – Daiana Ferreira de Oliveira

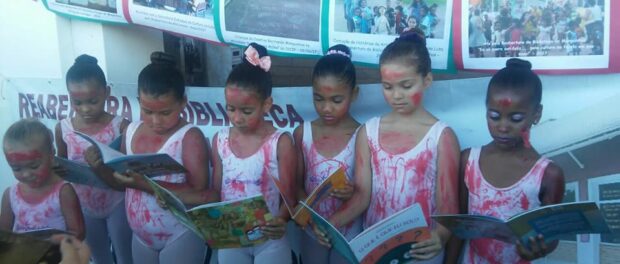

On March 29 a group of seven ballet dancers wearing baby pink leotards splattered with blood-red paint embarrassed Governor Luiz Fernando Pezão at the reopening of the Manguinhos Park Library (renamed the Marielle Franco Park Library in honor of the recently assassinated Rio city councillor). The ballet dancers lay on the floor, playing dead, with books in their hands. In front of the girls stood the director of the Ballet Manguinhos program, Daiana Ferreira de Oliveira, 29, who reminded those present of the 16 months during which the library had been closed by the state. But the site had not been abandoned: Oliveira and the girls took great pains to look after the cultural space throughout this period.

“If the library closes again after the election we’ll come back again. And we won’t leave,” promised Oliveira. “You can get up now, girls. You’re not really dead. This is just a reminder of how we are bleeding each day.”

Over the last year and four months Oliveira has become a sort of mayor of the library. In January 2017, one month after the library’s closure, Oliveira, pregnant with her first child, forced her way into the library. From that point onward she took care of the space. She was the one who kept the keys to the new padlock and the newly-fixed locks. She taught ballet classes there four times a week for the 200 girls from Ballet Manguinhos (financed by the Fiocruz Workers’ Union) and on Fridays she encouraged events like group discussions. She looked after the maintenance, painting, cleaning, archive conservation, and physical structure of the library. She only gave it all back to the state government one week before the official reopening, during which she gave a speech as part of the Ballet Manguinhos presentation.

The greatest challenge was to keep the building intact. Manguinhos’ library is surrounded by abandonment. Behind the library is a drug dealing spot inside an old National Supply Company (Conab) silo that has been invaded by drug users. In front of the building is the old Women’s House—a small building made of bricks where the State used to care for domestic abuse victims and offer skills training for women living in the region. The Women’s House was stripped of everything after it stopped functioning: the doors, windows, and all the equipment were stolen.

Without state support, the way to get by was to look to the parallel state. During the library’s reopening ceremony Oliveira revealed to Governor Pezão that she had had to ask the head of the Manguinhos drug traffic to prohibit any damage to the library building. A warning was sent out across the favela.

Oliveira is from a family of strong women. Her mother Rosali, 53, is a former cleaner who left formal education after primary school. Passionate about reading, Rosali is known as the best story-teller in the favela and she got her three daughters to do as many free courses as possible. The family lived in a house without a toilet until 2003. Even so, all three daughters went to university, with support from Prouni, a federal government program that gives study grants for private universities. The oldest daughter, 30, became disenchanted with her course in International Relations and instead became a “top make-up artist,” in Daiana Oliveira’s words. The youngest daughter, 22, is studying Social Communication and getting ready for an exchange program in Canada. Daiana Oliveira herself studied Physical Education, learned to dance through social projects, and now transforms the lives of other young people from the favela.

“Our method here is Russian ballet. We do very technical work,” says Oliveira, who has participated in several dance companies that, like her, offer free classes for children from favelas. “All our teachers came through social projects. One teacher from here [in Manguinhos] and three from Maré.”