For the original article in Portuguese by Michel Silva published by Favela em Pauta, click here.

It hasn’t been easy to understand the polarization of Brazilian political debate in recent years. Recently, a friend from the favela said that he went to get a haircut at a barbershop—where all the barbers are black, favela residents, and evangelicals—and the clients were discussing who to vote for in the next presidential election. Within a minute of conversation, he discovered that they were all supporters of Jair Messias Bolsonaro (Social Liberal Party, or PSL). His attempt to present and explain the proposals of other candidates—such as Boulos (Socialism and Liberty Party, or PSOL) or Haddad (Worker’s Party, or PT)—was in vain. It’s hard to engage in dialogue with Bolsonaro supporters since most are informed through WhatsApp, a cradle of fake news.

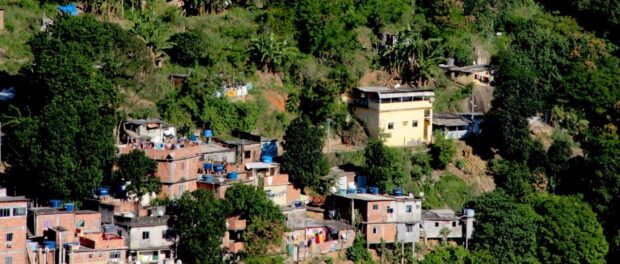

In March 2008, when former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva visited Rocinha to launch the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) public works in Rio’s favelas, residents raised a banner thanking the president for the project. A decade later, conservatism has advanced in favelas. Bolsonaro’s discourse has been gaining strength by way of moral issues. Lula is no longer the man of the hour. Fernando Haddad, Lula’s substitute, bears a huge responsibility. As he says in his slogan, “Haddad Is Lula.” He says he aims to “make the people happy again.” Nonetheless, Bolsonaro and Lula have something in common: both are populists.

Ten years ago, Lula was applauded for social investments in the country. Today, residents say that he has become tarred with the same brush. “He was swallowed up by the system’’ is the phrase I hear most commonly among Bolsonaro voters, including some who previously voted for Lula and Dilma. Conservative favela residents see the PSL candidate as a political outsider. Residents also recall the lack of self-criticism within the Workers’ Party: there was a lack of humility in failing to admit mistakes. But those who think that corruption in the country was born with the Workers’ Party are deceiving themselves. Corruption in Brazil has existed since colonial times.

But does the conservative wave in favelas stem from public insecurity in Rio de Janeiro? Or has the poor population turned against social policies?

Bolsa Família is a program that contributes to combating poverty and inequality in Brazil. Around 538,490 families are enrolled in the Unified Registry for Social Programs in the municipality of Rio de Janeiro. Of these families, 247,037 are beneficiaries of Bolsa Família. The average monthly benefit is R$170.88 (US$45) per family. Many families still need this benefit. Others believe that it is a sort of alms for the poor. However, conservatives are not clear on how we can reduce social inequality without social policies.

Former Army captain Bolsonaro is nostalgic for Brazil’s military dictatorship. And since our people have short-term memories, it’s worth recalling that during that period, the military carried out forced evictions—not to mention the militarized government presence in residents’ daily lives. Between 1962 and 1974, more than 140,000 people were removed from their homes—especially from wealthy areas such as Lagoa and Leblon, according to the report by the Rio de Janeiro Truth Commission. In 2018, we are experiencing a federal military intervention in Rio de Janeiro’s public security. The modus operandi remains the same: more and more military operations in favelas. Whether with Haddad or Bolsonaro, shootings will continue because the system is broken.

The PT didn’t know how to develop its grassroots policy in favelas and low-income neighborhoods over the years in which it was in power. The government’s inability to deal with poverty and violence allowed for the growth of evangelical churches in these territories. In addition to religious ideas, evangelism took advantage of the government’s absence and began to address social issues that people deal with every day. The fact that they offered education, security, and economic development helped to strengthen conservative thought. “I confess to you, it’s hard to understand—in the country of Carnival, people don’t even have food to eat,’’ sang MV Bill in the song “Only God Can Judge Me.”

Conservatism is not the only factor that bolstered Bolsonaro’s popularity. People are also desperate for a politician to bring something new. But again, Bolsonaro has nothing. He has been in the public sphere for twenty years and nobody knows what he has done for the state of Rio.

Nothing against moral debates—but our country is hungry. It’s impossible to live with the rise of unemployment, increasing poverty, cuts to Bolsa Família benefits, and the freeze on public spending for up to twenty years. With regard to the latter issue, Bolsonaro (belonging to the Social Christian Party at the time) voted in favor of making Brazil regress twenty years in two. Now, he presents himself as a solution for Brazilians.

Regardless of who will be next president of Brazil, we—the poor—must open our eyes and vote critically. Don’t let the anti-Workers’ Party sentiment lead us into a fascist scenario in which conservatives constantly speak of corruption and threats to the traditional family and to national values—but at the same time reproduce age-old political attitudes. Let’s be careful with whom we elect; otherwise, we’ll continue getting the short end of the stick.