For the original article in Portuguese by Mariana Assis published by Voz das Comunidades click here.

I’ve always been fascinated by words. Very much because of this, I made them my trade. Words allow one to narrate the world, to understand the dimension of things. In high school, my Portuguese teacher would always shout in class: “Words have power, do you hear?” Admittedly, I would usually laugh. It was kind of funny to see her emphasizing this so forcefully and expressively. Today, I see the importance of her incisive and necessary point: once we understand the words and everything they are capable of describing, we realize the real meaning of what is being said.

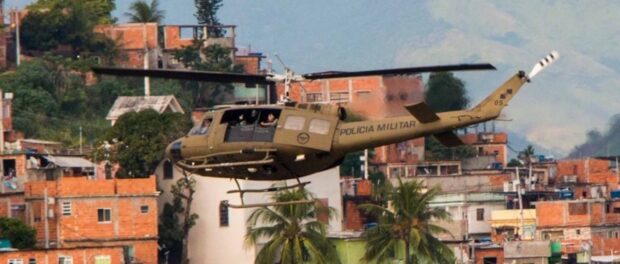

This reflection stems from concern over how cases of violence in Rio de Janeiro have been reported. In the first quarter of this year alone, Rio’s Institute of Public Security (ISP) recorded 434 deaths caused by the Military Police and Civil Police. This is equivalent to nearly five (4.82) deaths per day—a 21-year record since data collection began in 1998. Between Friday, May 3 and Monday, May 6, at least 13 people were killed by the police: four in Morro do Borel, one in Rocinha, and eight in Complexo da Maré.

Although it has been on the roof of the Uerê School in the Complexo da Maré favelas since July 2016, it was only last week that images of the above sign reading “School. Don’t Shoot” went viral on social media. The sign is an attempt to prevent the school from being targeted during police operations such to avoid the fate that befell Maria Eduarda, killed inside her high school in 2017.

Uerê has been assisting children with cognitive and emotional problems caused by violence-related trauma since 1998. Among other activities, the school trains students on how to handle situations of risk. That is: when they could be taking math, Portuguese, theater, and geography classes, students are trained in security procedures. This bears repeating: children are being trained in security procedures so they can protect themselves in situations of armed conflict. And yet, headlines state that shootouts “frighten residents,” provoking “yet another exchange of gunfire in so-and-so favela.”

Try to picture yourself in the same situation: you are in class at school. You begin to hear gunshots and your teacher interrupts the lesson. Students are instructed to get down on the ground. The bursts of gunfire intensify. The noise gets closer. The electricity cuts out. The messages popping up via WhatsApp are firm: everyone, stay put. There is no way to suppress it: tears begin to flow down your terror-stricken face. It’s horrific and yet banal. Two hours later and the tension hasn’t let up. A cell phone rings: the father of one of the kids in your class has just been shot. They’re dead. Would this frighten you?

‘Lost’ Bullets That Always Find the Same Bodies

This reporting method, hardly informative and rarely committed, continues to prevail even as mortality rates reach alarming levels. When the press normalizes the fact that one part of the city is huddling and dodging bullets while another is celebrating that public security policies to take on the “drug war” are “finally” underway, it ends up reporting on the situation with little clarity, rigor, commitment, or responsibility. The line “Stray Bullet Kills a Resident of Favela x” is as predictable [see the latest case here] as the final destination of that same bullet: it always finds the bodies of poor, black favela residents. Shocking.

The reduction of the meaning of the murder, machine-gunning, execution, or attack of people in favelas points not only to the selective importance attributed to certain lives through a perspective that deprives these individuals of their basic rights, but also to the non-accountability of those that pull the trigger, sustaining, producing, and supporting this discourse: “[The favela] is a violent place. They were going to die one way or another.” The irresponsibility of the press in portraying cases of violence in Rio is disorienting, inefficient, and desensitizing. It is important to emphasize that the media, as a powerful form of social communication, builds narratives that permeate society and informs public debate. Does “fright” account for the 434 deaths between January and March?

Beyond the context of Rio de Janeiro, across the country, according to the 2018 Atlas of Violence—a publication* of the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA) and the Brazilian Forum on Public Security—the number of people killed in Brazil is akin to that of countries at war, such as Syria in the Middle East. According to the study’s authors, this is because Brazil recorded 553,000 murders in the past 11 years. In Syria, which has been facing armed conflict for eight years, more than 550,000 have been killed, according to United Nations estimates released in 2018.

Efforts to normalize this violence tend to materialize in the reinforcement of subhuman stereotypes, justifying public policies skewed by gender, race, geography, and social class. The right to complete human development and a dignified, healthy life is also violated by the power of words—those same words that my teacher spoke of. Oftentimes, the reality is distorted amid shouts, cries, and demands for respect: “Stop killing us. Our lives matter.”

*2019 edition available here