This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and part of our partnership with The Rio Times. For the article as published in The Rio Times click here.

As the state of Rio de Janeiro climbs its way to becoming Brazil’s Covid-19 epicenter, favela residents find themselves fighting for their lives against the new coronavirus as well as an older, more familiar danger: the police.

The deadliest police force in Brazil, maybe in the world, Rio police are known for rushing armored trucks and helicopters into the favelas in what are described merely as “police operations.” Ostensibly targeted at local drug trafficking gangs, such operations often leave homes destroyed and black youth dead.

New evidence shows that such incursions have not only continued during the pandemic, they’ve actually increased in both frequency and lethality.

According to a new report by the Network of Security Observatories (ROS), a national monitoring body, Rio police operations increased 27.9% in April 2020 in comparison to April 2019. The number of civilians killed in these operations rose 57.9% in the same period. “The police are increasing violence,” said Pablo Nunes, research coordinator at the ROS, over WhatsApp. “They’re acting as though the favelas haven’t been left to fend for themselves during the pandemic.”

Official data from the state-operated Public Security Institute (ISP) for April 2020 regarding the total number of civilians killed by Rio police—a broader category than civilians killed during police operations—are yet to be released. However, in the likely chance that total police killings match ROS findings, April 2020 will be Rio police’s bloodiest April in history.

Rio 2019: A Most Violent Year

The jump in operations follows a year of record-level police violence. Encouraged by hardline rhetoric from the newly-elected Governor Wilson Witzel, Rio de Janeiro police killed 1810 civilians in 2019, the highest number since official records began in 1998, and nearly double the number killed by US police in the entire United States in 2019. 80% were black or brown.

On taking office, Witzel extinguished the state government’s security secretariat, the executive agency responsible for coordinating police activity. In its place, the state Civil Police and Military Police forces gained increased autonomy, with the two institutions earning their own secretariat-level offices. The combination of violent encouragement (Witzel suggested police snipers should shoot criminal targets “in their little heads”) and gutted oversight resulted in impunity for extrajudicial killings: a groundbreaking recent New York Times analysis concluded that Rio police “routinely gun down people without restraint, protected by their bosses and the knowledge that even if they are investigated for illegal killings, it will not keep them from going back out onto the beat.”

Preliminary statistics show that 2020, pandemic and all, may be following in 2019’s footsteps. The latest ISP data from January through end-March 2020 reveals little change: compared to the same period in 2019, police killings had dropped a mere 2%.

March 2020 had offered a glimpse of hope. Police killings dropped 14% in comparison to March 2019, in step with ROS findings on police operations for March 2020. As police shifted their efforts to enforce compliance with Covid-19 containment measures enacted March 16, the number of police operations plummeted, falling 74% in comparison to the first half of the month. The number of civilians killed in police operations in March 2020 dropped to 15, compared to 36 in March 2019.

However, this peace was short-lived. After the two-week reprieve, the slow in operations would end abruptly in early April, as police returned to cracking down on drug gangs, reducing attention given to Covid-19 containment. Nunes attributed this return to a loss of leadership in communicating and maintaining a common understanding of the gravity of the pandemic. “I think that this is over. This message isn’t echoed within the police corps anymore. Each is pursuing its own interests.”

Preliminary data indicate May may be no different. Between May 1 and May 19, police conducted an identical amount of operations as the same period last year, but killed 16.7% more civilians, according to the ROS report.

Interrupted Lives, Interrupted Donations

May’s figures provide further evidence for the startling amount of police violence favela residents and activists have faced over the last ten days, including:

- May 15, Complexo do Alemão, Rio’s North Zone. Thirteen are massacred in a police operation in the favelas of Nova Brasilia and Fazendinha.

- May 18, Acari, North Zone. 21-year-old Iago César dos Reis Gonzaga is allegedly tortured during a police operation. He is taken away in a police vehicle and found at a police morgue the next day.

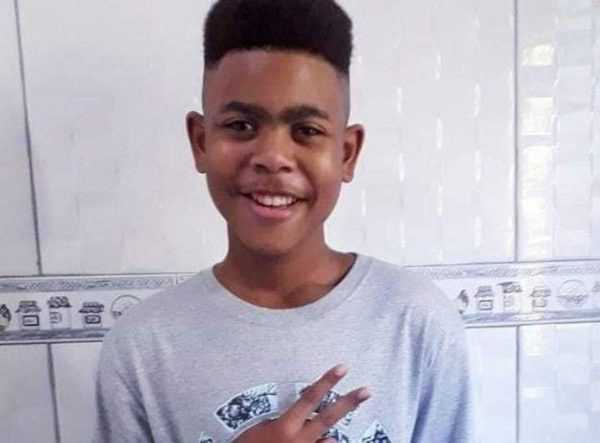

- May 18, Complexo do Salgueiro, São Gonçalo, Greater Rio. 14-year-old João Pedro Pinto Matos is shot in the stomach as police invade a relative’s house. He is taken away in a police helicopter and found at a police morgue the next day.

- May 20, City of God, West Zone. 18-year-old João Vitor Gomes da Rocha is shot during a police operation. Rocha is taken in an armored truck to a West Zone hospital and pronounced dead minutes later.

- May 21, Morro da Providência, downtown Rio. 19-year-old Rodrigo Cerqueira is shot during a police operation. He is taken to a nearby hospital and pronounced dead on arrival.

If the deaths themselves weren’t enough, police operations have directly impeded community efforts to mitigate the effects of Covid-19. Of the operations listed above, those in Acari, City of God, and Morro da Providência all coincided with vital food parcel distributions to those most in need who had lost income due to quarantine measures, and thus their livelihoods, in the favelas. Between March 13 and May 22, the Fogo Cruzado crossfire monitoring platform counted eight separate instances in which community food parcel distributions were interrupted by shootouts. All eight involved the presence of the police.

Meanwhile, in official documents, the only justification given for the operations by police is to “repress the drug trade,” with no further word on why it might be justified to increase operations at this current moment, amidst a surge in Covid-19 deaths in favelas.

“These initiatives that seek to feed the population that is suffering the most during the pandemic, they’ve been violently impeded by police operations,” affirmed Nunes, recalling the stated mission of the Military Police is to “Serve and Protect.”

In response to public outcry, Witzel held a May 22 videoconference with Rio state deputies, police chiefs, and civil society members—including City of God resident and CDD Covid-19 Response Front member Rodrigo Felha, founder of the Os Arteiros youth theater group—urging police to improve dialogue with community leaders and avoid undertaking police operations during Covid-19 relief campaigns.

“I think we can foster this integration, so that we can create greater communication and avoid that, in the moment that there is a need for a police search and arrest operation or an intelligence action, that there are people providing humanitarian services in these areas,” said Witzel.

Regardless, simply curbing operations during food distributions will do little to address the more lasting impact of State violence. Following the Friday May 15 massacre in Complexo do Alemão, local youth boxing gym and social program Abraço Campeão canceled its food and hygiene kit distributions through the rest of the weekend, citing continued police presence and a potential for more shootouts.

“We’re literally taking food to families here in Complexo do Alemão that are dying from hunger,” said founder Alan Duarte in a WhatsApp audio. Referring to the local moto-taxi volunteers that have helped the program distribute food kits, he added, “We have to prioritize their safety. It’s challenging because you don’t know whether you should protect yourself from bullets or from a virus.”

Speaking from the favela of Acari, site of the May 18 killing that interrupted food parcel deliveries, lifelong resident, sociologist and Fala Akari media collective member Buba Aguiar summarized: “It seems as though death is closer and closer to us, at the very moment that we are trying to keep our own from dying.”