This is our latest article on Covid-19 as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas.

Stories marked by successes, survival, struggles, and resistance are experienced by thousands of members of the LGBTI+ community who live in Rio’s favelas and in urban peripheries across Brazil. During the pandemic, we hear from various LGBTI+ activists and artists on important issues in the journey towards a more tolerant and inclusive society.

Violence and Survival

A reference organization on LGBTI+ issues in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro, the Conexão G LGBT Citizenship in Favelas Group completed 14 years of work in the Complexo da Maré favelas in March 2020. Its leader Gilmara Cunha, 36, who describes herself as a black trans favela woman, says the group was created to support a community that feels marginalized: “Society was designed for the middle and upper classes, and public policies are not geared towards the poor. We came up with a pilot project in Maré to transform the area. Now I understand that we were creating a survival strategy, because we understood that the policies would never reach us here and that we needed to keep our population alive.”

This feeling is shared by Carol Flávia Esteves, a trans woman born and raised in City of God. “I suffered all sorts of violations inside and outside my home. It was a massive struggle to get here, to the age of 43, alive. There were episodes where I had stones thrown at me, beatings, all sorts of LGBTphobia, but I made it.” She shares that early on she began mediating conflicts in the favela—or “untangling the mess,” as she prefers to describe it—with issues related to the LGBTI+ community. After she participated in the documentary Favela Gay, directed by Rodrigo Felha, it all finally sank in. “The film really opened my mind and helped me meet other people, activists from other favelas. That was when I noticed that I was already an activist, without ever having realized that,” she explains.

This feeling is shared by Carol Flávia Esteves, a trans woman born and raised in City of God. “I suffered all sorts of violations inside and outside my home. It was a massive struggle to get here, to the age of 43, alive. There were episodes where I had stones thrown at me, beatings, all sorts of LGBTphobia, but I made it.” She shares that early on she began mediating conflicts in the favela—or “untangling the mess,” as she prefers to describe it—with issues related to the LGBTI+ community. After she participated in the documentary Favela Gay, directed by Rodrigo Felha, it all finally sank in. “The film really opened my mind and helped me meet other people, activists from other favelas. That was when I noticed that I was already an activist, without ever having realized that,” she explains.

Another consideration shared by interviewees is that even important public policies, such as the criminalization of LGBTphobia in 2019, have had a lesser impact in the favelas because these policies fail to take the particularities of these territories into account. “We had a victory in the Supreme Court with the criminalization of homophobia, but I can guarantee with absolute certainty that this law will not be applicable to favela territories. The aggressor lives three houses down from mine. Where are we going to put this family after reporting them?” asks Cunha. She also stresses the social abyss that the measure exposes and remarked on the use of prison sentences, which could hurt favela residents even more: “My understanding is that this measure will not apply to society as a whole. The rich, who hold prejudices, will not go to prison. The poor, the black, and the favela population will be the ones to keep getting imprisoned. It will be another mass incarceration policy. How can we best think about guaranteeing life for this population in the favelas?”

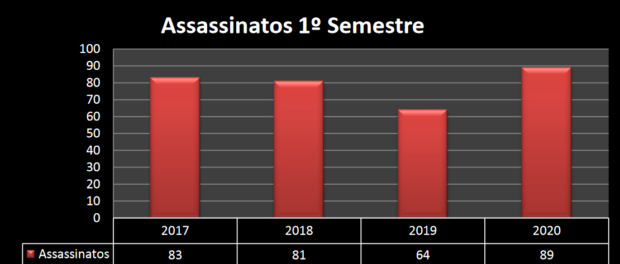

According to the latest report from the National Association of Transvestites and Transsexuals (ANTRA), published in June, 89 trans people were murdered in Brazil in the first six months of 2020, an increase of 39% from the same period of the previous year. The lack of consistent data from federal and state governments on violence against the LGBTI+ population shows that, in most cases, there is no permanent state policy to address this, but rather policies linked to individual administrations that may cease to exist when new leaders are elected.

Julio Pinheiro Cardia, former coordinator of the Office for the Promotion of LGBT Rights at Brazil’s Ministry of Human Rights and current director of the Brasília LGBTS+ Center, explains the problem: “Even with the available violence-related data, which is very little, we have no baseline for comparison when we collect the data. They are deaths in relation to what? How many people? How many LGBTIs? We need to have a better idea of the data universe to be able to start working with a clearer picture of our population.” To address part of the problem, the Brasília LGBTS+ Center is leading a campaign called “I Exist,” which seeks to include sexual orientation and gender identity in the 2021 census.

Coronavirus in the Favelas

During the coronavirus pandemic, transvestites and transsexuals who live in favelas are suffering more than usual. Esteves leads the efforts to support them in City of God. “We know that most of them [transvestites and transsexuals] leave home at night and many are ashamed of exposing themselves during the day, due to the prejudice they might suffer from standing in a line, for example.” For this reason, so that they can receive basic food baskets and hygiene kits, Esteves created an alternative option to receive these supplies at pre-scheduled dates and times, thus avoiding lines and exposure.

In Complexo da Maré, supporters of Conexão G are working from home and also making deliveries of basic food baskets. “Other projects have been paused, as there was no way to continue. We are seeking donations, raising funds. The trans population is very vulnerable. They can’t stop working because they pay rent. We don’t even have that, the privilege to stay at home and protect ourselves as people,” reflects Cunha.

In the state of Rio de Janeiro, the State Secretary of Social Development and Human Rights continues to provide services during the pandemic at its eight LGBTI+ Citizen Centers. They offer shelter as well as social, psychological, and legal assistance to these groups, and have expanded the number of cases taken in. In total, the centers recorded 2,611 services for clients from January to May 2020, while for the same period in 2019 there were 1,283. However, only one of the centers is located in Rio de Janeiro proper, which is insufficient for its over 6 million inhabitants.

Education and Empowerment

Heading the Grupo Pantera theater group are artists Gabriel Horsth, 23, and Paulo Victor Lino, 25, who have worked in the past as actors, producers, and directors. Both were raised in Nova Holanda, one of the favelas in Complexo da Maré, and staged the show Questão de Gosto (A Matter of Taste) in partnership with the leisure and cultural center SESC Madureira, which took the show to nine schools. They explore the theme of cyberbullying and gay dating apps. They are now moving on to a second phase in their research to update the show and include other groups from the LGBTI+ community. “We’ve noticed that we had very little research on the other groups, about how transsexuals, lesbians, and bisexuals use the apps, and so we’re rethinking the show with some new ideas we put together during quarantine,” reveals Lino.

Horsth highlights the importance of exchanges between groups from different communities. “We’re always trying to establish these links with other favelas. This is important to keep the work alive. When we first put together Questão de Gosto, we were in touch with Ponto Chic, a group from Nova Iguaçu, which is far from the central area of Rio. This dialogue was crucial for those young people to understand themselves as LGBTIs. Nova Iguaçu is an ultra-Christian municipality, with many churches. You could see there were a lot of issues among that group of young people. This dialogue broke barriers and reinforced our work.” He also explains how they have been working during the pandemic. “There has been a lot of discussion on what to produce during this quarantine period. With these virtual tools, we’re increasingly able to better connect these narratives, as well as study and work on productions.”

Horsth highlights the importance of exchanges between groups from different communities. “We’re always trying to establish these links with other favelas. This is important to keep the work alive. When we first put together Questão de Gosto, we were in touch with Ponto Chic, a group from Nova Iguaçu, which is far from the central area of Rio. This dialogue was crucial for those young people to understand themselves as LGBTIs. Nova Iguaçu is an ultra-Christian municipality, with many churches. You could see there were a lot of issues among that group of young people. This dialogue broke barriers and reinforced our work.” He also explains how they have been working during the pandemic. “There has been a lot of discussion on what to produce during this quarantine period. With these virtual tools, we’re increasingly able to better connect these narratives, as well as study and work on productions.”

Lino recalls that during the production of the show Questão de Gosto, they received threats from students at the schools where they were presenting the show, especially from those who support President Jair Bolsonaro. On the other hand, LGBTI+ students were able to see themselves portrayed for the first time in a work of art inside their own school, places which often lack such opportunities for dialogue about gender and sexual orientation. Lino also emphasizes that reality is different for favela residents: “Every day is about survival—surviving the government, surviving the coronavirus, surviving the state government, both how it serves the favelas and how it has been serving them during this pandemic. There is a different reality here in the favela, like a city within another city. It’s so crazy, but I think we’ve tried to find each other and create art to become stronger.”

Regarding the LGBTI+ pride commemorative events for June, Esteves says that all events that would have been in-person were cancelled due to the pandemic to avoid crowds. “People already live in crowded conditions here, so there’s no way to hold an event like a parade. There were some livestreams and posts on social media to celebrate LGBTI+ pride month.”

In Complexo da Maré, Conexão G organizes educational activities throughout the year, creating a space for reflection so that the cisgender and heterosexual residents can understand the reality of the LGBTI+ population, based on the idea that many of them there have shared experiences. “It’s a chain: the oppressor was at some point oppressed, and the violence is then unconsciously perpetuated. Many black cisgender males are prejudiced against the LGBTI+ population, holding the mentality of white people in a racial hierarchy, except they themselves are also oppressed all the time without realizing it,” argues Cunha.

Successes

“There has been significant improvement in the favelas in terms of prejudice,” says Esteves, from City of God. “The favela is a mother figure, it embraces people. However much your family casts you out, there will always be some family in the community that will support you. This is the warmth, affection, and love for each other in the favela.” Cunha also highlighted important advances in Complexo da Maré: “My victory is to see the LGBTI+ population on the street carrying out this transformation and this work of helping each other. There’s nothing better. This victory of being able to move around, to have the right to come and go within your own community, is very important.”

Horsth sees that many spaces were historically denied to the LGBTI+ population, but believes that joint work with the NGOs and support networks in the communities is a way to combat the prejudice through dialogue. “I think first we have to celebrate the fact that we’re alive, more than anything. And to also be proud of what you are and how you identify. This was an election where we elected the highest number of LGBTI+ representatives. Our LGBTI+ friends in the favelas are getting into universities, which we also need to celebrate. I try to stay positive with the good news and with the changes we are creating,” he concludes.