A show with singer Elza Soares and rapper Flávio Renegado marked the birthday celebrations for Marielle Franco, who would have turned 41 on Monday, July 27. The livestreamed concert “Elza for Marielle,” held on Sunday, July 26, was broadcast on the channel of the Marielle Franco Institute, an organization established by the lawmaker’s family to fight for justice, grow her legacy, and preserve her memory.

“We are leading several campaigns with many black women, because the Institute’s focus, beyond wielding Mari’s name, which is no easy task, is incorporating and inspiring other black women,” explained Anielle Franco, the councilwoman’s sister and executive director of the Marielle Franco Institute. In addition to Anielle, Marielle’s parents Marinete Silva and Antônio Francisco, her daughter Luyara Franco, and two of her nieces participated in the event.

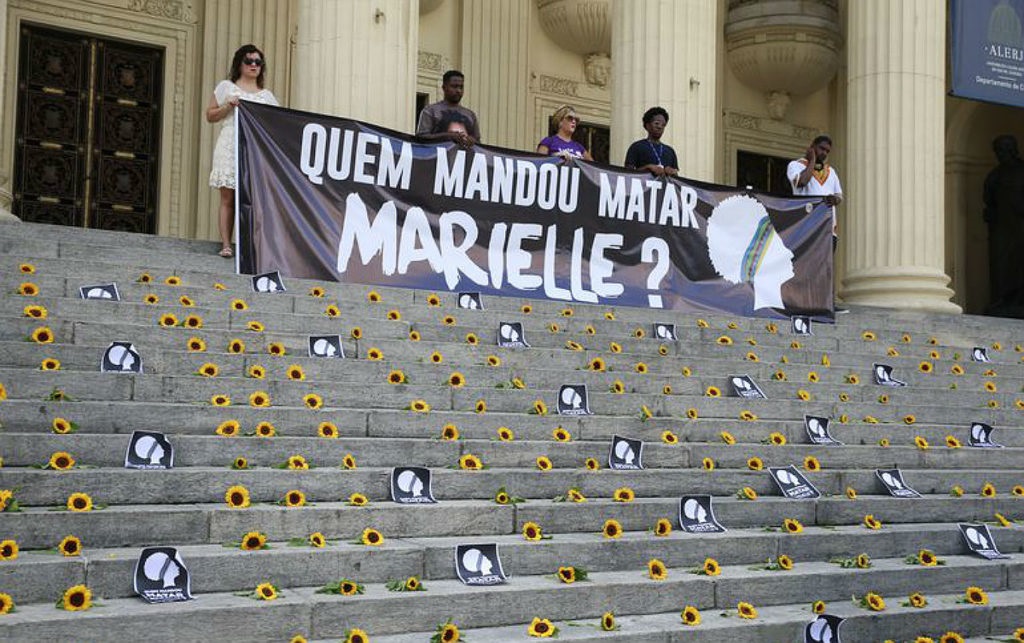

“Who ordered Marielle’s murder? Today is a day for celebrating the life of this great woman, but this question needs an answer: who ordered the murders of Marielle Franco and Anderson Gomes?” asked Elza Soares, who turned 90 last month. Both on- and offstage, the singer is a powerful voice against racism, sexism, and other forms of oppression. Soares and Renegado sung against gender-based violence and the genocide of black people, themes deeply present in Marielle Franco’s fight.

“It is very sad to see our people’s stories ending so early, so young. Like her, many, so many young people have their lives exterminated before they even begin. It’s a very unfair course of events. Because of this, it is necessary for Brazilians to understand that it isn’t enough to not be racist. It is extremely important and urgent that we be antiracist,” Renegado emphasized.

The show, which had nearly 7,000 people watching at once, was also among the ten most-discussed topics on Brazilian Twitter. In addition to celebrating the councilwoman’s life, the show raised funds for the Marielle Franco Institute’s projects.

Marielle’s Fight Lives On

If she were alive, Councilwoman Marielle Franco would finish her first term this year. Of the four years that democracy guarantees to elected officials, Marielle and the team that composed her collective mandate worked together for 15 months, a little over a year. With Marielle, black women, people from Rio’s peripheries, and the LGBTQI+ community made it to the Rio de Janeiro City Council, with the power to propose public policies that directly affected the existence of their bodies and their territories.

A little more than two years after the councilwoman’s assassination, the Marielle Franco Institute works to plant new seeds. With the launch of the Antiracist Electoral Platform (PANE) this month, the institution began a series of actions to support the candidacies of black women in the next municipal elections, which will be the first following Marielle’s death. In the 2016 elections, black or brown women made up only 5% of elected councilmembers nationwide. Marielle’s victory, with the fifth-most votes in the city, brought the only black woman to the current session of City Council.

The seeds planted by Marielle blossomed in the 2018 elections, when three of her former aides were elected to the state legislature, where they are now the only three black women. Throughout Brazil, the number of black candidates, especially women, grew, but it remains a long road to changing the typical profile of a legislator. According to the Superior Electoral Court (TSE), in the last elections, black men and women made up only 4% of elected candidates across Brazil.

PANE arose with a mission to change the structure of Brazil’s political system, mobilizing society to pressure political parties and the TSE to adopt policies that guarantee greater equity in elections. The platform aims to promote more black women into positions of power, where they can change the structures that historically have kept away and violated black, peripheral, and LGBTQI+ communities. In doing so, they keep Marielle Franco’s struggle and memory alive.

Raised in Complexo da Maré in Rio’s North Zone, the councilwoman fought for the right to life, especially that of black and peripheral youth, as her primary political issue. Marielle began her activism in human rights after enrolling in a community-based college entrance exam preparatory course and losing a friend, victim to a stray bullet during a shootout in Maré. Publicly, she positioned herself against police operations in favelas.

On the day before she was assassinated, in response to the death of yet another young black person at the hands of the police, she asked on Twitter: “How many more will need to die for this war to end?”

Mais um homicídio de um jovem que pode estar entrando para a conta da PM. Matheus Melo estava saindo da igreja. Quantos mais vão precisar morrer para que essa guerra acabe?

— Marielle Franco (@mariellefranco) March 13, 2018

In Brazil, the chances of being a homicide victim are directly related to the color of your skin. Data from the Institute of Public Security show that police killings in the state of Rio reached a new record in 2019. The Inequality Map produced by Casa Fluminense revealed that 81% of the people killed by the state were black. This number goes up to 100% in the cities of Petrópolis, Seropédica, Guapimirim, Cachoeiras de Macacu, and Rio Bonito.

The results of the war on drugs and of increasingly militarized security policies were part of Marielle’s daily life. During the time she worked as an aide to the State government’s Human Rights Commission, alongside Marcelo Freixo, Marielle supported family members of victims of violence, including the relatives of police officers. She criticized the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) program, which was the topic of her master’s thesis.

Among the bills she proposed to Rio’s City Council were proposals to promote and guarantee rights for women, black people, favela residents, and the LGBTQI+ community. In a little over a year, 20 of her bills were presented, some after her assassination.

One of her bills that was approved by the City Council addresses the legalization of the profession of motorcycle taxi drivers, a very common means of transportation in Rio’s favelas. The text, signed by Marielle and others, became a law in June 2019. The creation of the Women’s Dossier of Rio de Janeiro, which facilitates data collection about support given to women who are victims of violence, was also approved. The bill was presented to the Council and approved after Marielle’s death.

As president of the Commission for the Defense of Women’s Rights, the councilwoman presented plans for the expansion of access to legal abortions, nighttime nurseries for working mothers, humanized birth and prevention of maternal mortality, and combatting harassment on public transit, with all of the aforementioned being signed into law. She also presented a bill that would include Lesbian Visibility Day in the city’s calendar, a proposal that was rejected.

Marielle believed it was necessary to bring visibility to this topic so that actions could be carried out at the institutional level. In Brazil, between 2015 and 2017, at least 126 women were killed just for being lesbian. This statistic is part of an unprecedented study carried out by the Nucleus of Social Inclusion at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. The actual numbers would of course be even higher, however, as there are no specific official records about hate crimes against lesbian or bisexual women in Brazil.

Who Ordered Marielle Franco’s Murder?

After over two years and four months, Marielle Franco’s family continues to tirelessly demand that the authorities respond to the crime. The attack against the councilwoman’s car on March 14, 2018, in the North Zone neighborhood of Estácio, also resulted in the death of driver Anderson Gomes. Since then, family members of the victims, Marielle’s party, the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), and a wide range of human rights organizations are fighting for the identification of the people who ordered the crime.

As investigations move forward, indications of a possible relation between state agents and organized crime have appeared. As of now, a retired sergeant and a former military police officer have been arrested under suspicion of having fired the shots at the car. In June 2020, a fire-fighter was also arrested, suspected of having participated. However, questions about the motivations of the crime and the identity of who ordered the assassination remain unsolved.