December 15th–I had taken just a few steps down Rua Asa Branca when Bezerra’s familiar voice rang out. The Resident Association’s inimitable president was sitting in a barbershop, his face covered in shaving foam, being spruced up ahead of a landmark event in the community’s history. Over recent months this favela of about three and a half thousand people in Rio’s rapidly developing West Zone had received a range of urban upgrading works. It was the first meaningful act of state intervention since the community was established in 1986 and Mayor Eduardo Paes himself would be coming to inaugurate the works.

When I had first visited Asa Branca a couple of months before the work was just getting underway and so I had been able to see some of the original dirt roads. The transformation was impressive. The roads had been covered over with smooth concrete, dotted with drains and bordered by attractive sidewalks. The latter, although too narrow for more than one person to use at a time, are a symbol of ‘formality’ that is clearly prized by local residents. Although rain from the previous night had left some large puddles at points where the road was uneven, the curbs and drains together should prevent any larger build-up of water, which has been a common problem in the past. The community had solidly backed the incumbent Paes in the recent mayoral elections and the improvements were taken as proof that their faith had been justified. The sentiment among residents gathering outside the association building for the inauguration was a mixture of gratitude and renewed pride in their community.

When I had first visited Asa Branca a couple of months before the work was just getting underway and so I had been able to see some of the original dirt roads. The transformation was impressive. The roads had been covered over with smooth concrete, dotted with drains and bordered by attractive sidewalks. The latter, although too narrow for more than one person to use at a time, are a symbol of ‘formality’ that is clearly prized by local residents. Although rain from the previous night had left some large puddles at points where the road was uneven, the curbs and drains together should prevent any larger build-up of water, which has been a common problem in the past. The community had solidly backed the incumbent Paes in the recent mayoral elections and the improvements were taken as proof that their faith had been justified. The sentiment among residents gathering outside the association building for the inauguration was a mixture of gratitude and renewed pride in their community.

However, the state’s presence in Asa Branca remains uneven. The Rua do Canal at the edge of the favela has also mostly been paved, but somehow life there feels more precarious. This is the poorest and most recently settled area, lying on the bank of a contaminated stream that is strewn with litter. The Prefeitura has promised to clean it, but there is no sign yet of this happening and in fact the construction work nearby has added to the degradation. From here another transformation comes into view that is likely to affect Asa Branca as much as its internal upgrading. Looking south, dozens of enormous apartment buildings stretch far into the distance. This is the frontier of Rio’s elite expansion, welcoming those priced out of the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca, as well as speculators expecting a rapid rise in property values after the arrival of new transport systems and the construction of the nearby Olympic Park.

However, the state’s presence in Asa Branca remains uneven. The Rua do Canal at the edge of the favela has also mostly been paved, but somehow life there feels more precarious. This is the poorest and most recently settled area, lying on the bank of a contaminated stream that is strewn with litter. The Prefeitura has promised to clean it, but there is no sign yet of this happening and in fact the construction work nearby has added to the degradation. From here another transformation comes into view that is likely to affect Asa Branca as much as its internal upgrading. Looking south, dozens of enormous apartment buildings stretch far into the distance. This is the frontier of Rio’s elite expansion, welcoming those priced out of the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca, as well as speculators expecting a rapid rise in property values after the arrival of new transport systems and the construction of the nearby Olympic Park.

At the back of Asa Branca, facing the wall that marks the border between these two worlds, lies a group of four houses that seem to have been overlooked by the urban upgrading altogether. “We’ve received nothing,” said Antonio, the owner of one of the houses. The paving had ended twenty metres earlier, as had the new drains and street lamps. Even worse, he and the others claimed the works had interrupted their rudimentary sewage system, causing it to overflow so that dirty water had built up in their collective alleyway. “I’ve been crying all week,” said Maria. “Ninety per cent of the residents have received improvements, but we are the ten per cent,” Antonio declared, “and for us it’s got worse.” As Hélio, an elderly, disabled resident, emerged on crutches from the last of the four houses, Antonio asked rhetorically “Is this a dignified way for a disabled citizen like this to be treated?” I asked why they thought they had been left out, but nobody knew. A road connecting the condos to the new highway on the other side of Asa Branca is likely to be routed through here. Will the area surrounding these houses be urbanised then? Or have they been marked for removal? No one here knows.

At the back of Asa Branca, facing the wall that marks the border between these two worlds, lies a group of four houses that seem to have been overlooked by the urban upgrading altogether. “We’ve received nothing,” said Antonio, the owner of one of the houses. The paving had ended twenty metres earlier, as had the new drains and street lamps. Even worse, he and the others claimed the works had interrupted their rudimentary sewage system, causing it to overflow so that dirty water had built up in their collective alleyway. “I’ve been crying all week,” said Maria. “Ninety per cent of the residents have received improvements, but we are the ten per cent,” Antonio declared, “and for us it’s got worse.” As Hélio, an elderly, disabled resident, emerged on crutches from the last of the four houses, Antonio asked rhetorically “Is this a dignified way for a disabled citizen like this to be treated?” I asked why they thought they had been left out, but nobody knew. A road connecting the condos to the new highway on the other side of Asa Branca is likely to be routed through here. Will the area surrounding these houses be urbanised then? Or have they been marked for removal? No one here knows.

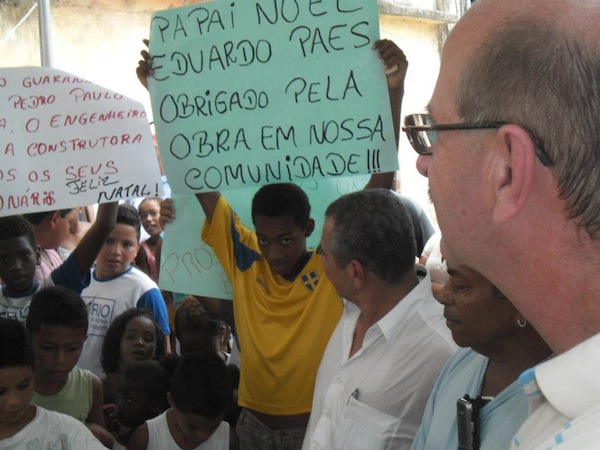

Back at the Residents’ Association a canopy, film crew and microphone had been set up, and by now a large crowd was eagerly anticipating the arrival of the Mayor. They were to be disappointed. After about an hour-and-a-half and several announcements predicting his imminent arrival, Bezerra was forced to tell the crowd that Paes had been held up inaugurating the TransOlímpica highway in distant Ilha do Governador, and would not be able to make it. A hum spread through the crowd, but quickly died down as Thiago Mohamed, Subprefeito of Barra da Tijuca and Jacarepaguá, took the stand in the Mayor’s place. He emphasised that Paes wished he could be there and that the works were evidence of his administration’s commitment to helping those in the city who most need it. Bezerra reiterated this point and read out, from placards held up by local children, a series of messages to the Mayor in absentia. One read “Santa Claus Eduardo Paes thank you for the works in our community!!!”

Back at the Residents’ Association a canopy, film crew and microphone had been set up, and by now a large crowd was eagerly anticipating the arrival of the Mayor. They were to be disappointed. After about an hour-and-a-half and several announcements predicting his imminent arrival, Bezerra was forced to tell the crowd that Paes had been held up inaugurating the TransOlímpica highway in distant Ilha do Governador, and would not be able to make it. A hum spread through the crowd, but quickly died down as Thiago Mohamed, Subprefeito of Barra da Tijuca and Jacarepaguá, took the stand in the Mayor’s place. He emphasised that Paes wished he could be there and that the works were evidence of his administration’s commitment to helping those in the city who most need it. Bezerra reiterated this point and read out, from placards held up by local children, a series of messages to the Mayor in absentia. One read “Santa Claus Eduardo Paes thank you for the works in our community!!!”

The French social theorist Michel de Certeau distinguished between the ‘strategies’ of governments and the ‘tactics’ of dominated groups, in particular with regard to the construction and use of urban space. ‘Strategies’ are long-term plans, purportedly based on grounds of universalism and scientific rationality, but all too often reflecting the narrow perspectives of political and economic elites. ‘Tactics’ are the practical solutions developed by those on the receiving end, finding ways to make them relevant, minimise the damage they inflict and maximise their benefits. The less wealth and political influence people possess, the more constrained is their potential for tactical action. In this context communities like Asa Branca are regularly forced to make difficult decisions, sacrificing some entirely legitimate demands in exchange for the realisation of others, and even tolerating the neglect of some of its members as a kind of collateral damage.

The French social theorist Michel de Certeau distinguished between the ‘strategies’ of governments and the ‘tactics’ of dominated groups, in particular with regard to the construction and use of urban space. ‘Strategies’ are long-term plans, purportedly based on grounds of universalism and scientific rationality, but all too often reflecting the narrow perspectives of political and economic elites. ‘Tactics’ are the practical solutions developed by those on the receiving end, finding ways to make them relevant, minimise the damage they inflict and maximise their benefits. The less wealth and political influence people possess, the more constrained is their potential for tactical action. In this context communities like Asa Branca are regularly forced to make difficult decisions, sacrificing some entirely legitimate demands in exchange for the realisation of others, and even tolerating the neglect of some of its members as a kind of collateral damage.

In a system where policies can change overnight without warning and where social gains are at constant risk of being overwhelmed by the financial imperatives of a runaway property market, the formulation of tactics is that much more difficult. The Morar Carioca programme, currently underway in Asa Branca and seven neighboring favelas in this part of the city, invites resident participation in identifying key areas for upgrading actions and will result in a much more comprehensive upgrade than those completed haphazardly and unilaterally by Rio’s Secretary of Public Works last week. However, with the threat of removal looming over other favelas in the area, new questions are raised. Are the works delivered in Asa Branca this past Saturday an attempt to bypass the comprehensive participatory program and weaken the collective strength of the historically closely-allied Curicica communities?

In a system where policies can change overnight without warning and where social gains are at constant risk of being overwhelmed by the financial imperatives of a runaway property market, the formulation of tactics is that much more difficult. The Morar Carioca programme, currently underway in Asa Branca and seven neighboring favelas in this part of the city, invites resident participation in identifying key areas for upgrading actions and will result in a much more comprehensive upgrade than those completed haphazardly and unilaterally by Rio’s Secretary of Public Works last week. However, with the threat of removal looming over other favelas in the area, new questions are raised. Are the works delivered in Asa Branca this past Saturday an attempt to bypass the comprehensive participatory program and weaken the collective strength of the historically closely-allied Curicica communities?

Tactical action is also exhausting for those responsible. Fifteen or twenty minutes after Bezerra and the Subprefeito had jointly unveiled a plaque declaring Asa Branca’s upgrading complete, the visiting dignitaries had gone and the crowd had dispersed. The freshly shaven Bezerra sat alone on a plastic chair looking pensive. I congratulated him on an achievement that he more than anyone else had made possible, and asked him how he felt. “I’m tired,” he replied. He would go and stay with his brother for a few weeks, rest up and enjoy the holidays. Then in January he would return and work would resume: “A luta continua.” The battle continues.