This article is the latest contribution to our year-long reporting project, “Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas: Deconstructing Social Narratives About Racism in Rio de Janeiro.” Follow our Rooting Anti-Racism in the Favelas series here.

“Baby, I feel ready to welcome you, to love you and care for you!!! May God bless us! My bliss has a name: Maya or Zayon,” posted Kathlen Romeu on social media a week ago.

Ver essa foto no Instagram

13 weeks and 3 days with the love of my life…

I confess they’ve been quite different! Something new happens all the time! Sometimes, I wake up startled, thinking this isn’t real but, then, a roaring hunger hits me, a headache, a drowsiness that just won’t quit, uncontrollable nausea and heartburn… that I guess only Jesus can save me from! At times I think my burps will get me arrested! Yeah, that’s what it’s been like, and then I remember: I’M PREGNANT!

And despite it all, as I write this text today, I feel extremely happy and fulfilled. I feel that I now have an even bigger reason to be the greatest ass-kicker of all time! You know that girl/woman that everyone admires and is proud of?! Now she just wants to be more and more!!! And everything for this little being I’m carrying in here!

I’m discovering myself as a mother and it scares me to think of how it’s going to be… I laugh out loud, I cry and I get scared. It’s a mixture of feelings. Maybe the craziest in the world, but I’ll laugh at all of this later on… thank you Lord for blessing my womb and allowing me to carry THE LOVE OF MY LIFE!!!

Baby, I feel ready to welcome you, to love you and care for you!!! May God bless us!My bliss has a name: Maya or Zayon

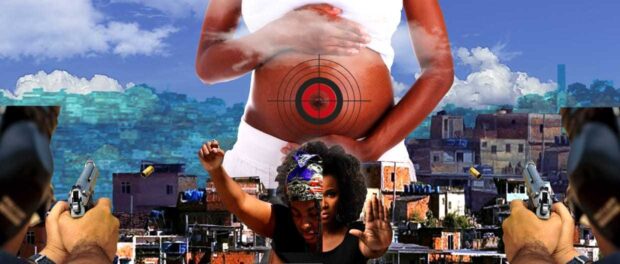

Interior designer Kathlen Romeu, 24, a smiling, young, pregnant woman, and her baby, were killed while walking beside her grandmother during what was, supposedly, a shootout between the police and drug traffickers in Complexo do Lins, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, on June 8, 2021. The Military Police denies there was a police operation happening at the time, and claims that a patrol car passing by the spot reacted to shots fired by traffickers, a version refuted by family and witnesses who, on June 8, saw one more black family add members of its ranks to an interminable list of young favela resident victims of the State, shot to death during a police operation. Romeu’s grandmother and mother describe how the police invaded the home of a resident and hid there until they saw what were, allegedly, drug traffickers and began shooting from within the house. While the family suffers this unbearable loss, the spokesman for the Military Police defends its officers’ actions in the media and echoes his version of events across social media.

Na tarde de hoje, policiais militares da #UPPLins foram atacados a tiros durante patrulhamento na localidade conhecida como “Beco da 14”. Após cessarem os disparos, os agentes encontraram uma mulher ferida e a socorreram ao Hospital Salgado Filho, no Méier. #PMERJ pic.twitter.com/v3laTFa9jv

— @pmerj (@PMERJ) June 8, 2021

This afternoon, military police officers from the Lins Pacifying Police Unit were shot at while patrolling the spot known as “Beco da 14.” Once the shooting stopped, the agents found a wounded woman and offered assistance, taking her to the Salgado Filho Hospital, in Méier.

A survey compiled with data taken from shootout monitoring platform Fogo Cruzado shows that almost 700 women were shot in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region from 2017 to today. The study included victims of stray bullets and homicides. In these four years, of the 681 women hit by gunfire, 258 died. 15 of those shot were pregnant, eight of whom perished. Ten babies were shot in their mothers’ wombs and a single one survived. In addition, there is a growing trend of police lethality, which has increased even during the pandemic and despite social isolation.

After emblematic cases, such as the murder of 14-year-old João Pedro by Civil Police officers during an operation in Complexo do Salgueiro, and considering the substantial growth of State-perpetrated violence, the Rio de Janeiro Public Defenders’ Office, Educafro, Global Justice, Maré Development Networks, Conectas Human Rights, The Unified Black Movement, ISER, the Right to Memory and Racial Justice Initiative, Straight Talk Collective, Fala Akari Collective, Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence, and Mothers of Manguinhos went to the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) to officially question the necropolitics that currently prevails in the state of Rio de Janeiro. The STF demanded explanations from the state government and, on June 5 2020, a temporary decision was issued affirming the Claim of Non-Compliance with a Fundamental Precept 635 (ADPF 635), which became known as the “ADPF of the favelas.” ADPF 635 was issued by Supreme Court Justice Edson Fachin suspending police operations in the favelas of Rio during the pandemic, except in “absolutely exceptional” circumstances.

Complexo do Lins is made up of 12 to 14 favelas. What happened there is yet another explicit violation of the ADPF, maintaining the historic trend of murders committed in favelas and the structural racism exhibited by the lethality of police operations.

On Wednesday, June 9, the day after Kathlen was murdered, black and favela movements organized a protest in the designer’s memory, joined by community leaders from Complexo do Lins who had already been rallying supporters through social media for a march leaving from the Light electricity utility’s substation on Rua Lins de Vasconcelos, at 4pm. The destination was the spot where Kathlen was murdered. The young woman and her baby were buried at the Catumbi Cemetery that same afternoon. Meanwhile, throughout Lins, police roadblocks targeted moto-taxis taking residents to the rally’s meeting point.

Gradually, five police vehicles and approximately 25 officers took position, slightly removed from the protesters who were beginning to convene and spread out signs on the ground. Local leaders agreed ahead of time on the route to be followed with a major from the Military Police. The group took off a little before 5pm towards Rua Lins do Vasconcelos, chanting. Calling for “the abolition of the Military Police!” and chanting “Kathlen, present!”, along with “black and favela lives matter!” Some protesters tried to close off both lanes of traffic but were stopped by police, who restricted the crowd to a single lane.

Followed by TV helicopters, there was no ignoring the voices that called for justice and peace in the neighborhood and across the city’s favelas. There were tears, shouts, and anger but, above all, raised fists in memory of the two lives that were violently interrupted. Some looked out their windows, from buildings. Others spread out white banners and shouted slogans, while drivers honked and clapped, even if many others paid no attention or gave no importance to the march for the right to life and in memory of Kathlen.

When the protest arrived at the place of the murder, one minute of silence was observed, followed by residents’ shouts for the march to continue to the entrance of the Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) headquarters, two streets away. According to some organizers, there was no point in walking all that way without, in the end, letting the police involved in the shooting hear what residents had to say. By this point, practically only residents were still marching, with most people from outside Complexo do Lins having remained at the crime scene or having left. The act ended at the UPP, while the police listened, motionless, with faces covered and weapons drawn, listening to the residents’ shouts.

According to Lins resident Cristiane Martins, a social worker, researcher and writer for community newspaper A Voz do Lins, there is an urgent need to analyze data related to the territory to engender productive public policies. “There is nothing here in terms of health, education, income generation and employment. Complexo do Lins has its community leaders, but almost nothing as far as the State is concerned, not even NGOs. This results in the marginalization of people, and violence in our surroundings. Education is the main thing [we need].”

Martins says that “Lins seems to have been forgotten, lacking in public policies. We have no security, there have been several other cases of residents who were victims of this same violence. Often you don’t hear about it, and then nothing happens. For how much longer?”

Residents feel that when people from outside the community join a protest, the police have no option, they follow the crowd and listen to the shouts for change. And that was what happened. However, when only residents are present, as in the case, for instance, of the protest that happened on the evening of June 8 on Estrada Grajaú-Jacarepaguá, things end with a severe police response including fire, stones and bombs. In these cases, the police tend to act with violence, abuses, and no dialogue. The Wednesday act was important because it reflected the voice of the community where Kathlen grew up and lived in up to month before she was murdered.

For decades, public security policy for favela territories has been carried out in an extremely abusive, barbaric, and arbitrary manner and with an undeniably racist bias. One month before Kahtlen’s death, there was the Jacarezinho Massacre, where 28 people were killed as a result of a police intervention—the biggest massacre in the history of the city. How can a nine-year-old child, resident of Jacarezinho, live her life normally after watching a policeman execute a drug trafficker with a rifle, shooting him twice, point-blank inside her own bedroom, right next to her bed? How can this child keep going to school, when the notebook she uses is smeared with the blood that drained from that slain black body? So many people, most of them young, have had their lives interrupted, despite having so much life left to live. This savagery that takes away the lives of favela residents in the name of the war on drugs. This war against the poor has got to end!

During the protest, mourning became a verb in memory of Kathlen and of so many other mothers, parents, daughters and sons killed by the State. Márcia Jacinto, mother of Henry, killed at 16 by the police, unburdens the pain of all the mothers of victims of the State, of victims of the black genocide. When one mother cries, all mothers cry:

Ver essa foto no Instagram

An Act for Kathlen – Marcia cries from the heart: When one mother cries, all mothers cry

Kathlen Romeu, 24, a black woman who was four months pregnant, was murdered in Complexo do Lins, in Rio’s North Zone. The young woman, who had moved away from the favela due to the constant police confrontations, came back to the community on Tuesday, June 8, to visit her grandmother. Kathlen’s family, and many witnesses, blame the police for her death. This version is denied by the Military Police, who claim to have assisted the victim. Kathlen’s grandmother, who was with the young woman when she was hit, says the police only offered aid after she begged for help and assistance.

The black and favela movements organized a protest for this Wednesday, June 9 in Lins, the day after Kathlen’s death. Mourning becomes a verb of remembrance and Márcia Jacinto, mother of Henry, killed at 16, pours out the pain felt by every mother of a victim of the State, of victims of the black genocide. When one mother cries, all mothers cry.

#JusticeForKathlen@Alecerqueiraa

The mothers and children of Rio demand peace! Why don’t the mothers and the children of Rio’s favelas have the right to live?

About the author: A resident of Lins, in Rio’s North Zone, Alexandre Cerqueira has a degree in International Relations and develops primary education projects in favelas using photography and video production as language tools.

About the artist: Born and raised in Complexo do Alemão, David Amen is co-founder and communication producer of the Roots in Movement Institute, a journalist, a graffiti artist, and an illustrator.