This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.

This piece presents the results of a study carried out in the field, on the structure of electric power and access to electricity in the Morro do Sereno favela in Complexo da Penha, North Zone of Rio de Janeiro. This article will present relevant information on electricity in public thoroughfares and in private residences, and more broadly acros the city’s favelas and peripheries.

Electric Bills and Public Lighting in Rio de Janeiro

The Municipal Energy and Lighting Utility, RioLuz, is part of the Municipal Secretariat of Conservation and Environment, responsible for the planning, expansion, maintenance, and modernization of the city’s public lighting system. The Fund for the Public Lighting of Municipalities (COSIP) contributes to the improvement of lighting on public thoroughfares such as squares, viaducts, and roads; only religious temples and homes with a monthly consumption of up to 100kWh (kilowatt-hour) are exempt from this charge. Transfers from private electricity providers, such as Light, in the case of the city of Rio de Janeiro, to the municipal governments, are realized monthly for the operation, maintenance, and expansion of public lighting networks, such as the change of light bulbs, installation and maintenance of utility poles, etc.

The monthly consumption of homes is calculated through the reading of an electric meter to know how many kWh have been consumed. The final amount charged is calculated by multiplying that month’s consumption in kWh by the price per unit (which already includes taxes), and adding to this a public lighting fee. The National Electricity Agency (ANEEL) defines the base rate and price per unit. Taxes (ICMS—tax on goods and services; and PIS/PASEP and COFINS—taxes that promote public welfare programs) are added on to the final price and vary between regions. According to Article 149-A of the National Tax System, each municipality is authorized to collect the fee, which is mandatory.

The monthly consumption of homes is calculated through the reading of an electric meter to know how many kWh have been consumed. The final amount charged is calculated by multiplying that month’s consumption in kWh by the price per unit (which already includes taxes), and adding to this a public lighting fee. The National Electricity Agency (ANEEL) defines the base rate and price per unit. Taxes (ICMS—tax on goods and services; and PIS/PASEP and COFINS—taxes that promote public welfare programs) are added on to the final price and vary between regions. According to Article 149-A of the National Tax System, each municipality is authorized to collect the fee, which is mandatory.

Calculation of an electric bill in a Morro do Sereno favela home:

Monthly consumption: 259 kWh

Price per unit: R$0.921

Amount consumed: 259 kWh X 0.921 = R$238.53

Public Lighting Fee: R$12.42Total owed: R$238.53 + R$12.42 = R$250.95 (US$49.28)

“The country’s economic scenario does not help families meet the rising costs of electricity, especially during the pandemic,” says Tatiana da Souza, 30, a resident of Morro do Sereno. In Penha Circular, the neighborhood in which Morro do Sereno is situated, for example, most of the streets are upgraded with buildings, shops, and churches, and have a large flow of people and cars, which demands a lot of electricity and public lighting, as well as frequent maintenance. On the streets, the concern is with maintenance and with light bulbs being changed. Inside homes, the concern is with access, with the grid’s safety, and rising prices.

Another constant worry for families is to avoid energy waste and the unnecessary expense that results from it. In the public sphere, RioLuz is responsible for keeping streetlights lit and avoiding waste. 2021 marks ten years of an agreement signed between the city of Rio, Light, and Banco do Brasil to finance the Reluz program. Reluz aims to promote and encourage the development of efficient energy systems, since favelas still have very old utility poles with mercury light bulbs.

After a decade of the public-private partnership signed by the Rio municipal government, the Reluz program is receiving new boosts with the aim of modernizing the city’s entire lighting system by 2022, with the installation of 450,000 LED light points across the city. “The plan is to substitute 35,000 metal or concrete lampposts with fiber ones. This substitution with new materials will bring benefits, which include the intelligent management of the public lighting network, lower environmental impact and a 60% reduction in energy consumption. The [historic] metal, colonial lampposts not replaced will be painted with electrical insulating paint,” states RioLuz on its website. The operation’s objective is energy efficiency, putting into practice the conservation of non-renewable resources, conscious consumption of energy and measures against waste. By next year, the Luz Maravilha program aims to have reached the entire city and is already beginning to be implemented in the favelas.

“I believe that it could improve things significantly. In fact, they’ve been putting up LED lights in Complexo do Alemão,” says Caroline Mara Vieira, 27, who is a receptionist in a residential condominium and lives in what is called Área Cinco of Complexo do Alemão, in Rio’s North Zone.

On the 1746 mobile app, the Rio municipal government’s call center, it is possible to request the installation of public lighting, as well as of lampposts, the relocation of utility poles, and maintenance services. However, feedback from users does not encourage other clients to download the app. “Terrible experience. I’ve been requesting you change the lamppost and light bulb in front of my house for 15 days, but no one has turned up to carry out the repairs and you send me a message saying the repairs have been made,” writes Edson Ferreira.

High Rates as a Barrier to Electricity Access for Low-Income Residents

Favela residents complain about abusive rates despite the poor quality of services delivered. That is the case of Natalha Sant’Anna Gomes, 23, a biology undergraduate at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) who lives in the neighborhood of Bonsuccesso, on the edge of Avenida Brasil. “Bills have been increasing and this interferes with my family’s income. With the price variations, we have stopped buying certain things, and have an income equivalent to one and a half minimum wages.”

despite the poor quality of services delivered. That is the case of Natalha Sant’Anna Gomes, 23, a biology undergraduate at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) who lives in the neighborhood of Bonsuccesso, on the edge of Avenida Brasil. “Bills have been increasing and this interferes with my family’s income. With the price variations, we have stopped buying certain things, and have an income equivalent to one and a half minimum wages.”

Precarious public lighting and bad electric service for homes determine people’s lives in unthinkable ways. Natalha, for example, has chosen to attend classes in the morning instead of the evening, a choice made to protect herself from the dangers that the dark streets represent, particularly for women. Not that men don’t feel unsafe in the dark, but they fear being robbed, whereas women fear being assaulted or raped.

Since they almost never receive visits from Rio’s electric utility, Light, to resolve issues in their area, Natalha and her neighbors have seen their problems add up. According to Natalha, “it’s only when a truck brings down the wiring [as the wires are low and the truck drives into them] that maintenance takes place. But now this almost never happens because we put a pole up here at home.” Self-construction and self-organization are the immediate solutions which many residents resort to as a way of guaranteeing their access to electricity with a minimum level of quality, security, and dignity.

“The night lighting in our city is terrible. You can’t see anything with that pinkish light, and I’m scared to walk down the streets, especially as a woman walking alone! I think that a brighter bulb would be the main improvement to public lighting,” says Natalha.

In favelas, infrequent repairs weaken the electricity system, contribute to its scarcity, and consequently lead to the expected use of “gatos,” clandestine electrical connections associated with inadequate formal distribution of energy. Energy providers calculate how much has been siphoned by these clandestine connections and distribute the amount amongst paying consumers. The costs get shared out, but the grid does not.

The Electrical Grid in Data: Structure and Access to Electricity in Morro do Sereno

Things are no different in Morro do Sereno: residents complain about exorbitant prices, the lack of infrastructure for the distribution of electricity, and public lighting. The community has approximately 3,500 residents, according to the Morro do Sereno Residents’ Association, and around 1,500 homes distributed in 16 streets and 20 alleys. To service this number of residents, there are 200 lampposts, of which five do not currently work. In the higher part of the favela, some families live in precarious conditions due to the lack of expansion of the electrical grid. In this area, some houses live with “single-phase” power and suffer from constant blackouts and intermittent electricity, known as “blinking lights,” since the voltage is weak, with the grid sometimes functioning at half capacity.

The following quantitative research project was carried out by and with residents, and presents a panorama of access to electricity in Morro do Sereno. As with most favelas in Rio, there is a data blackout on Sereno. This renders invisible much of the social reality of these areas and makes it harder to develop and implement efficient public policies. It is in resistance to this policy of active ignorance that this study made itself necessary.

This statistical work was carried out by a local resident, with local residents, about local residents and for local residents, but also for society in general and public authorities. From the very start, the study benefited from the help and guidance of Conceição Barbosa, president of the Morro do Sereno Residents’ Association. In the absence of official data, the data on estimated population and number of homes produced by the Residents’ Association are the most reliable. The project also received special help from Cristine Germano, 50, known as “Titi,” who works tirelessly as a Social and Cultural Change Agent in Morro do Sereno. As well as these two women, the entire process was supported by local activists and leaders, family health officers and networks of friends and families to get a better understanding of the area itself. All helped put together this study, also from a methodological point of view and regarding each one of its phases.

Following conversations and interactions with the actors listed above, the data analyzed below were collected during the month of June 2021, both in person and remotely. In-person interviews and questionnaires were all realized in accordance with coronavirus protection protocols. Through the questionnaires, it was possible to outline a framework with populational information, including socio-economic profile, access to infrastructure, to the electrical grid, and government subsidies. It was possible to get a sense of the local perception of the services delivered by the electricity provider and the level of community self-organization necessary to guarantee access to electricity, as well as the neighborhood’s feelings about public lighting on streets and alleys. The research also aims to find out if there is a connection between public lighting and public security in the view of both residents and public security officers who work in the area. The statistics of Morro do Sereno speak for themselves.

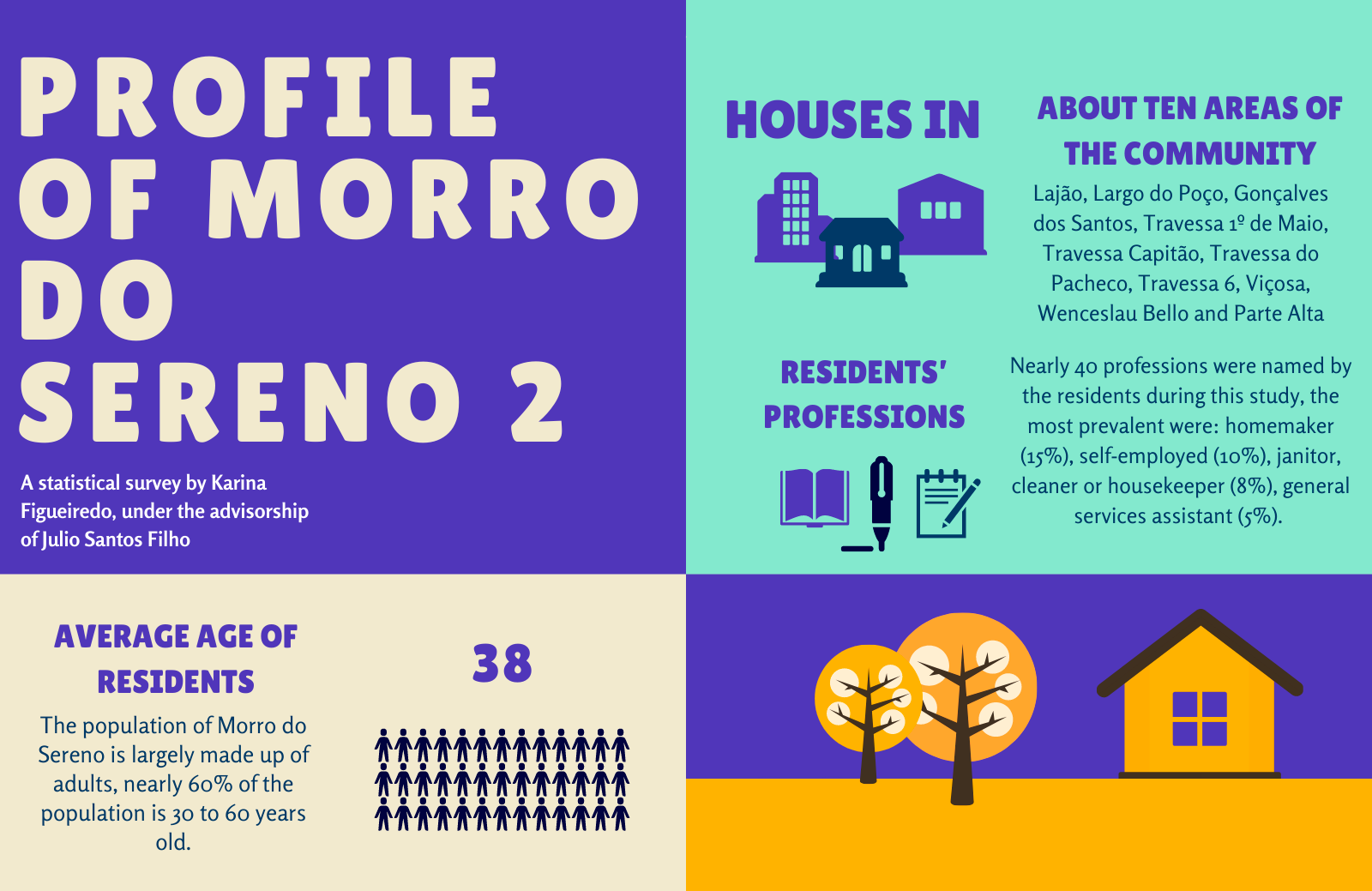

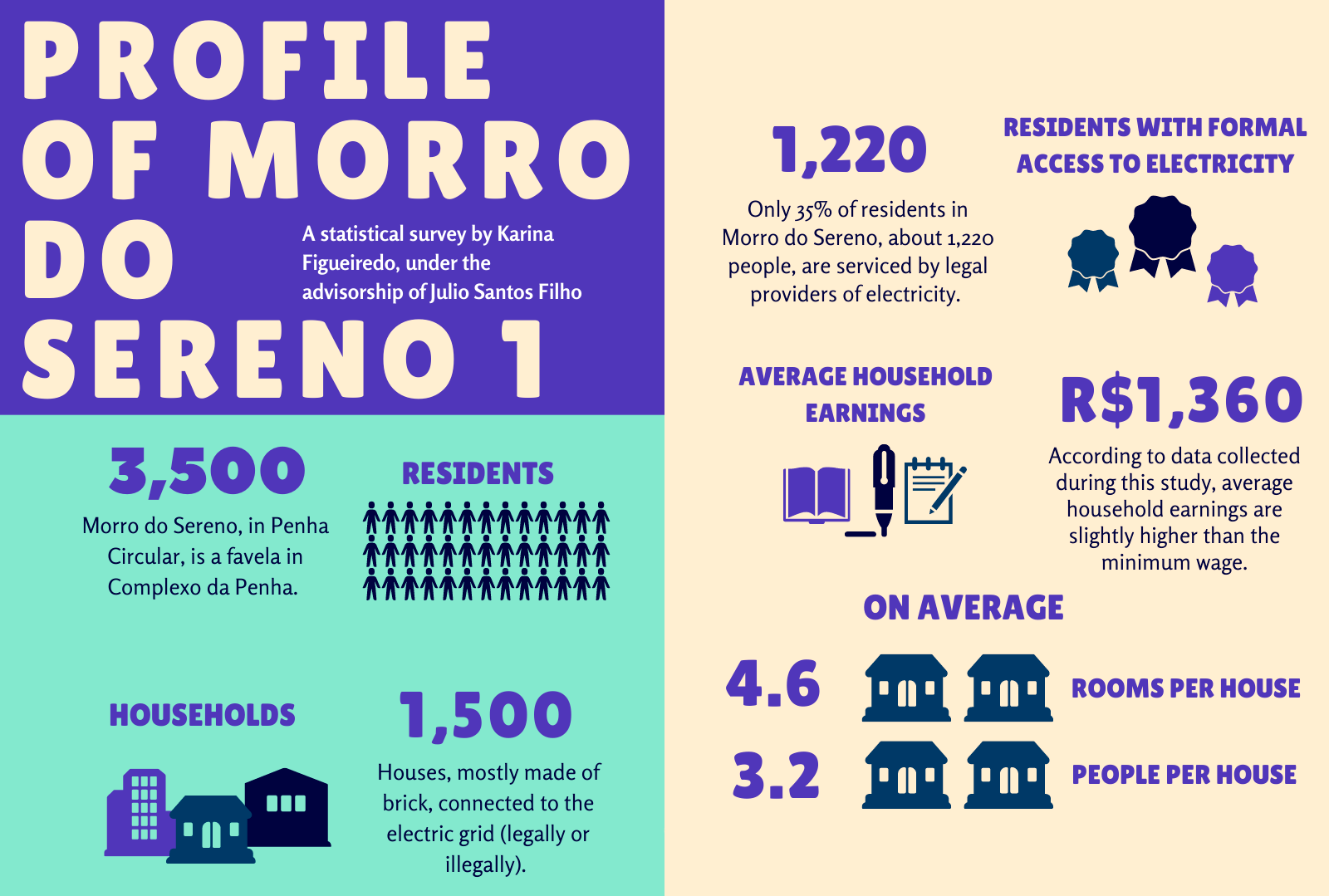

Bearing in mind that there are 3,500 residents, this study is based on replies from 96 Morro do Sereno inhabitants, a figure representing a 95% rate of statistical confidence. By listening to residents from diverse localities within the favela—Lajão, Largo do Poço, Gonçalves dos Santos, Travessa 1º de Maio, Travessa Capitão, Travessa do Pacheco, Travessa 6, Viçosa, Wenceslau Bello and Parte Alta—data found that there are, on average, 3.2 residents per house, the average size of which is 4.6 rooms. It can be said that, including a bathroom and a kitchen, most houses in Sereno have a living room and one or two bedrooms. In 28.1% of the houses, there are five rooms; 16.7% have three rooms; and 9.4%, six rooms. In its vast majority, the neighborhood is made of brick houses, connected—whether formally or informally—to the water and electricity networks but which depict the families’ humble standard of living. In the highest part of the favela, ending on the edge of the Atlantic Forest, it is possible to come across houses made of wood, wattle and daube, some of them connected to single-phase power, some without electricity.

Morro do Sereno is a relatively small favela, with a small population. It covers approximately 4.5km² of one of the mountainsides on which Complexo da Penha is situated, facing the neighborhoods of Penha Circular and Brás de Pina. It is not a densely populated favela, with around 780 inhabitants per km².

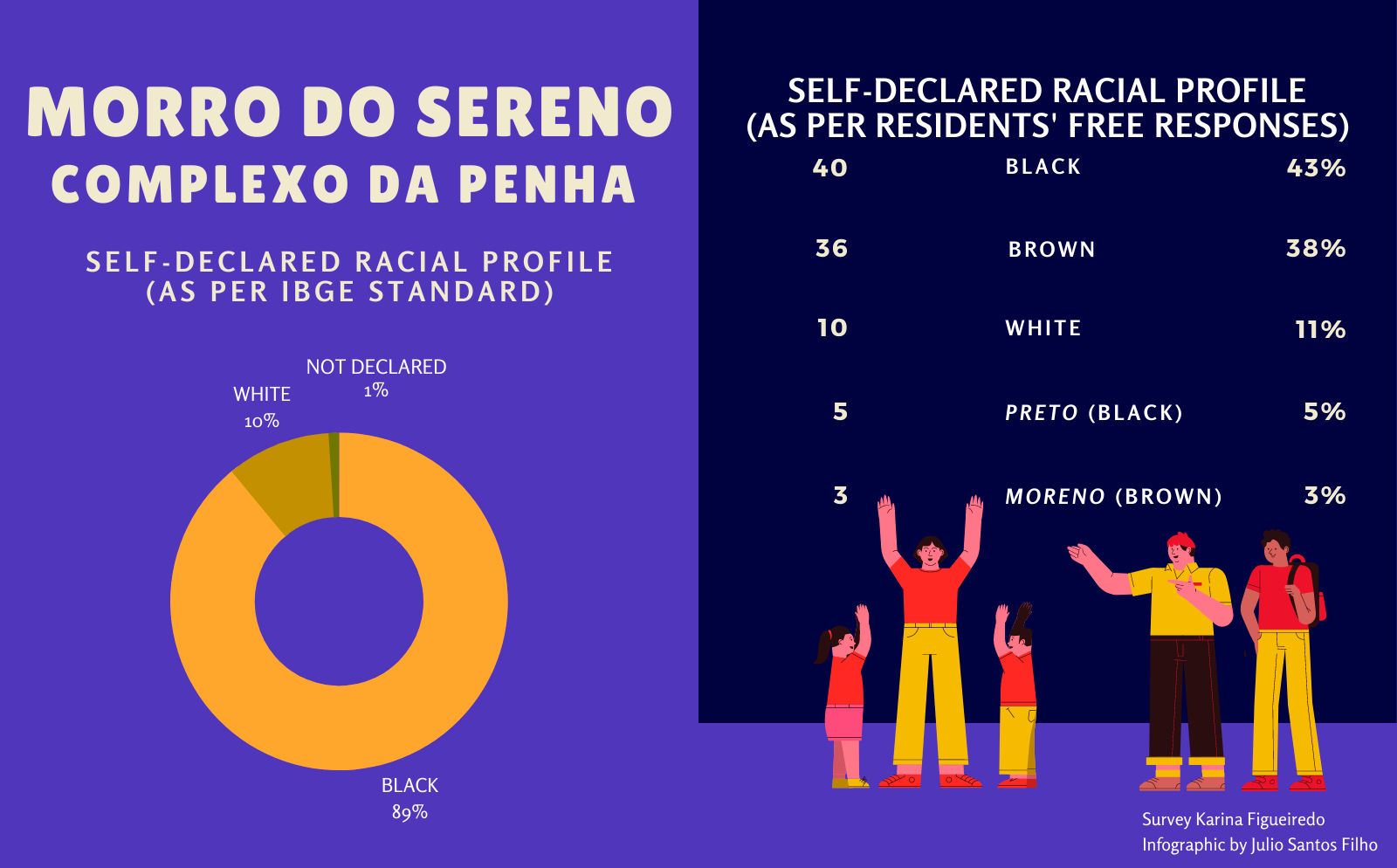

Primarily black, 89% of the population of Sereno declares itself to be black or brown (including both pardo and moreno); just 10% replied white and 1% “declined to say.” And its profile is not young: the average age of interviewees is 38 years old, almost 10 years above the national average of 29.5 years old for favela residents in Brazil. The majority of interviewees said they were employed or active in some capacity (95%). The most commonly cited professions were homemaker (14.7%), self-employed (9.5%), cleaner, housekeeper, or day worker (8.4%), and general services assistant (5.3%).

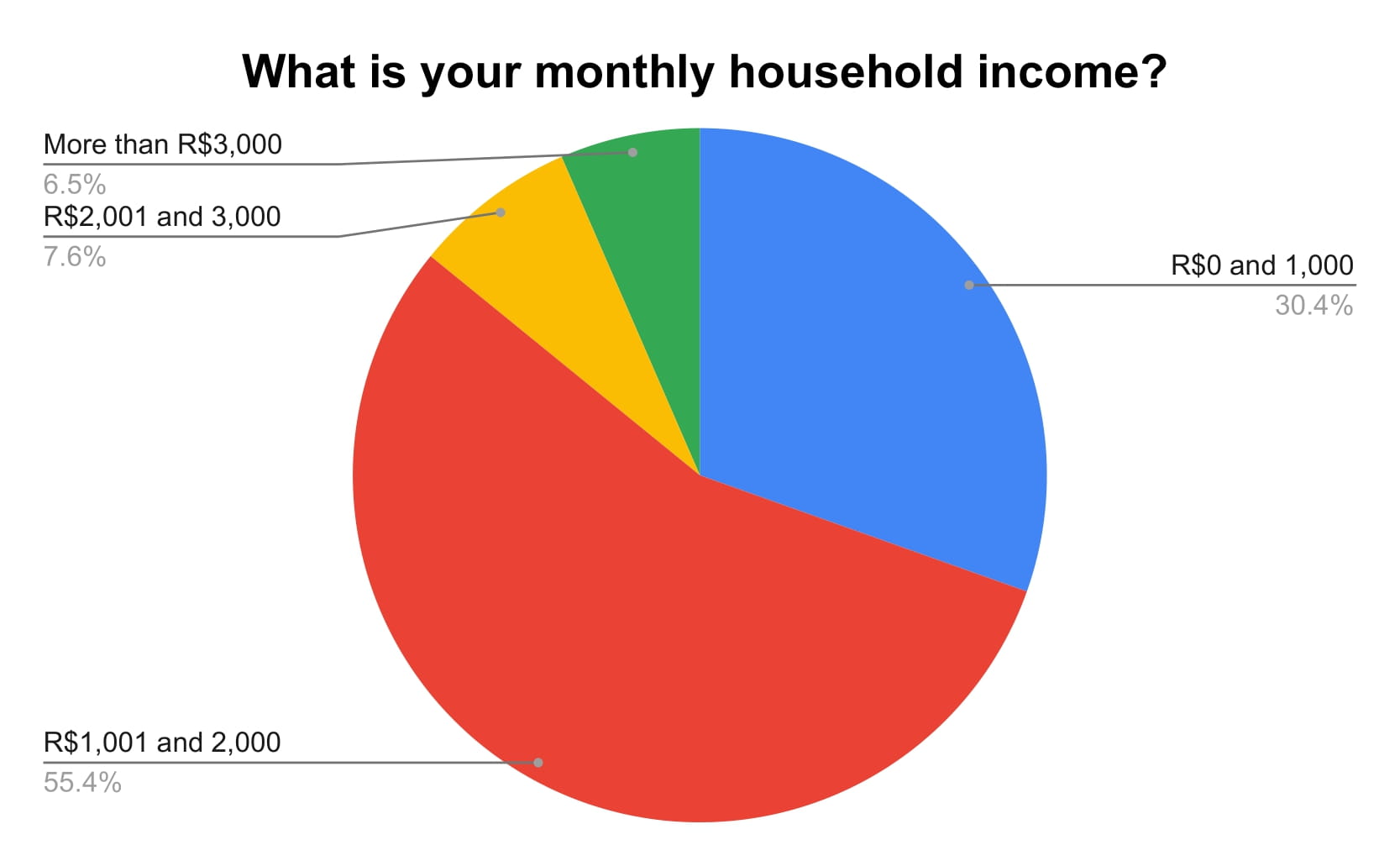

Another figure included in this analysis is the average income which, in Sereno, stands at around R$1,360 (US$257) per household per month. This is slightly above one Brazilian minimum wage, to support, on average, 3.2 people per month, coming out to R$425 (U$80) per resident per month. Only 5% of the population interviewed for the study declared themselves idle. Idle or not, the current state of economic, social, and food insecurity is undeniable, with family budgets also affected by growing inflation.

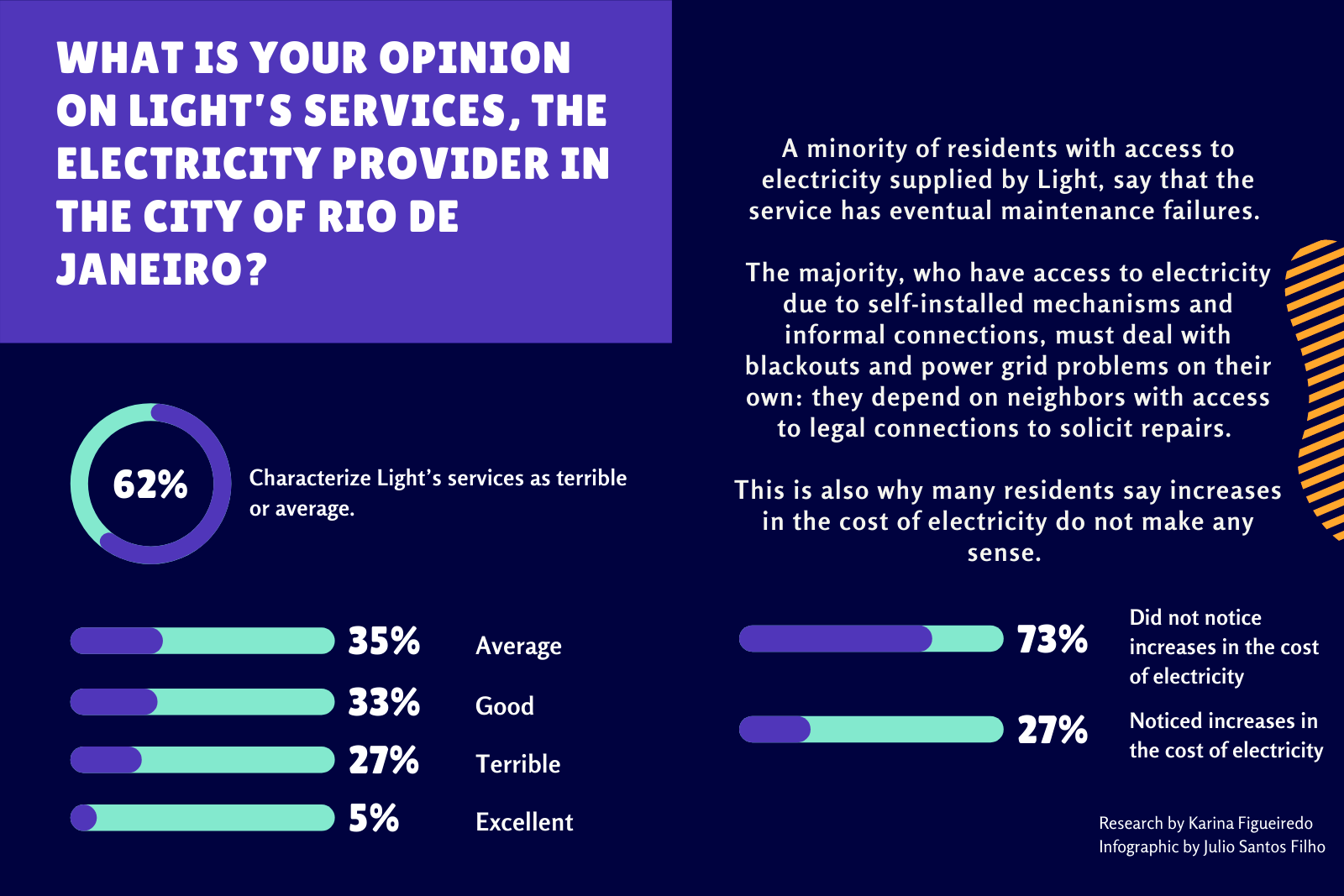

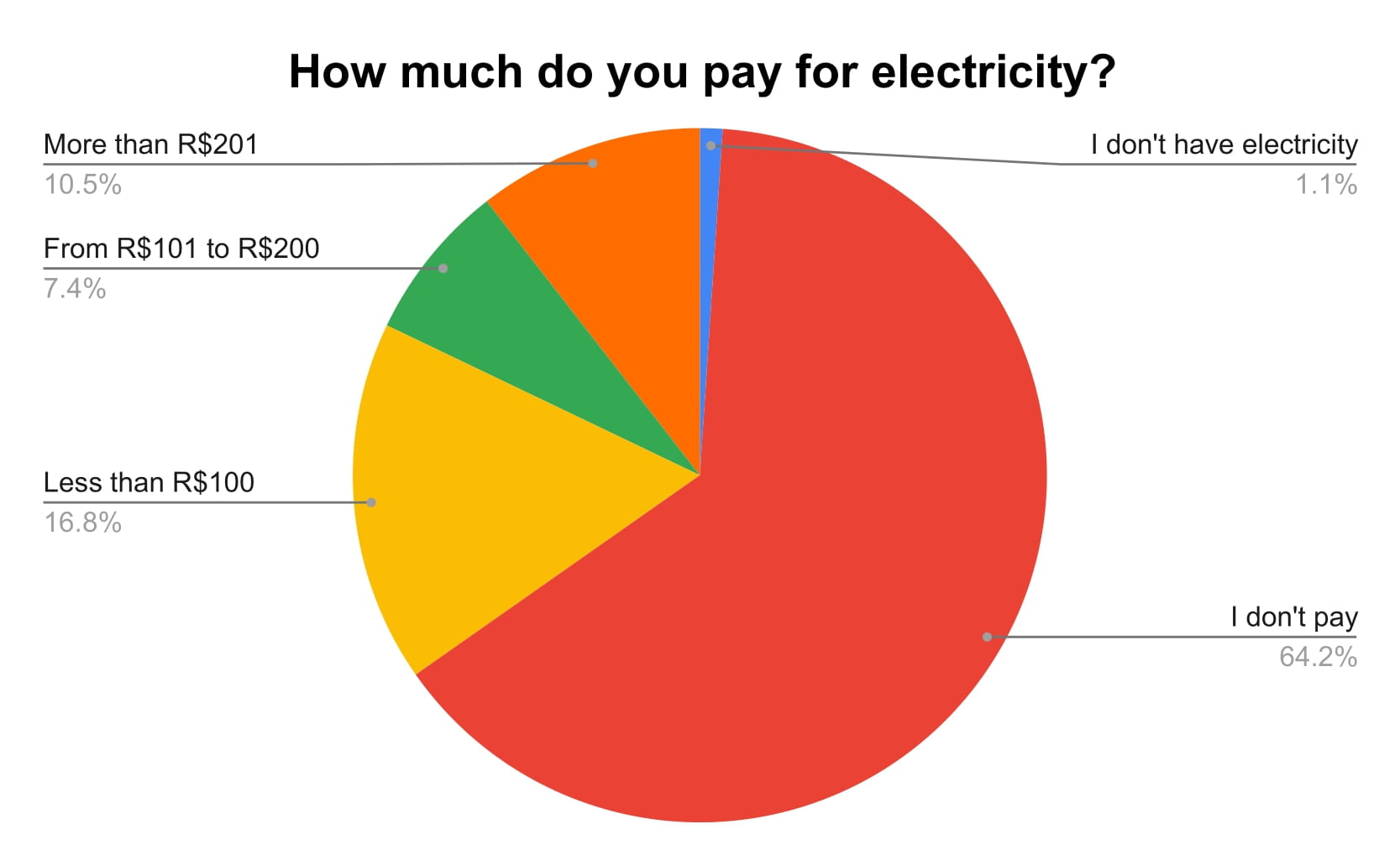

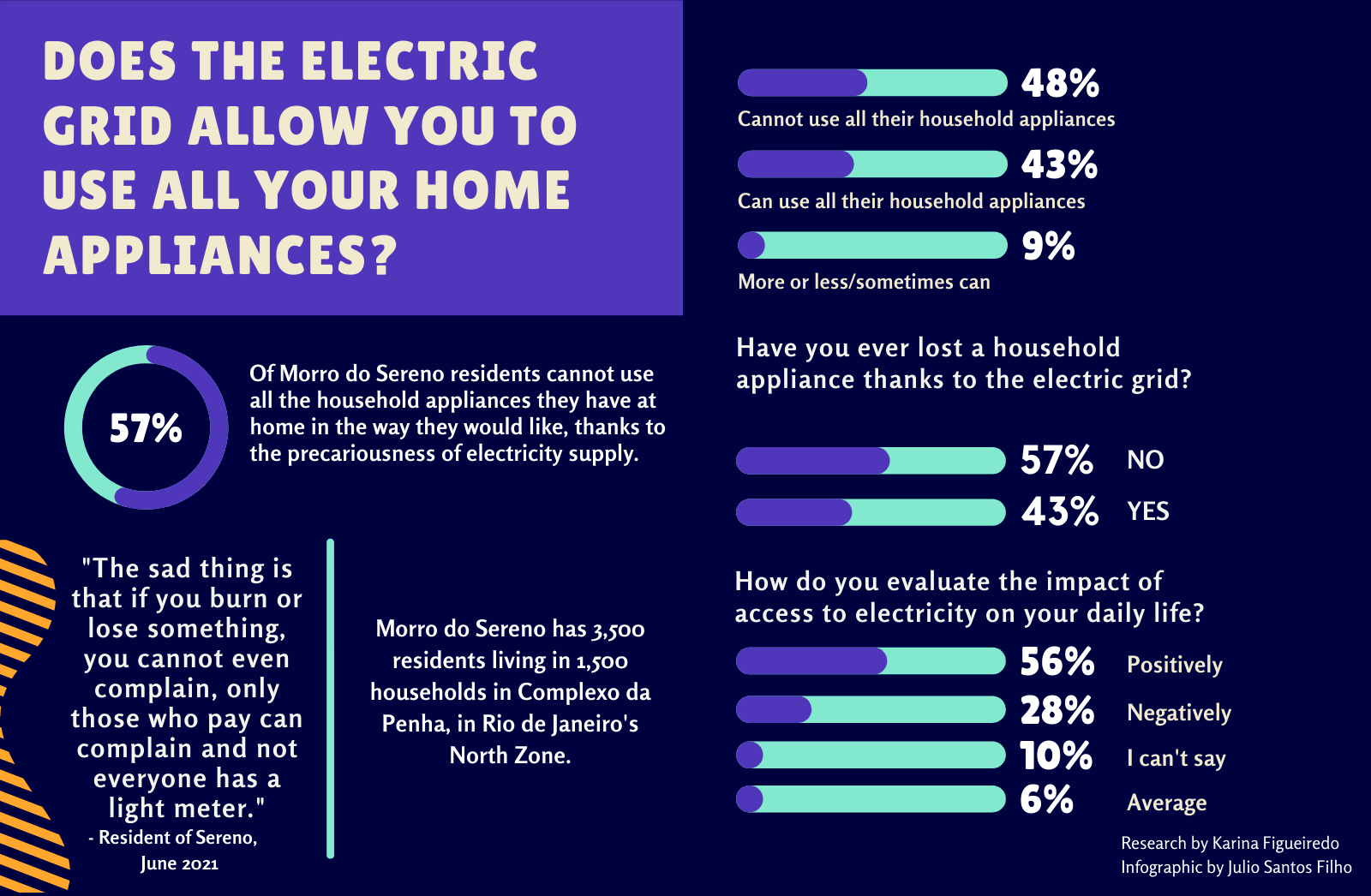

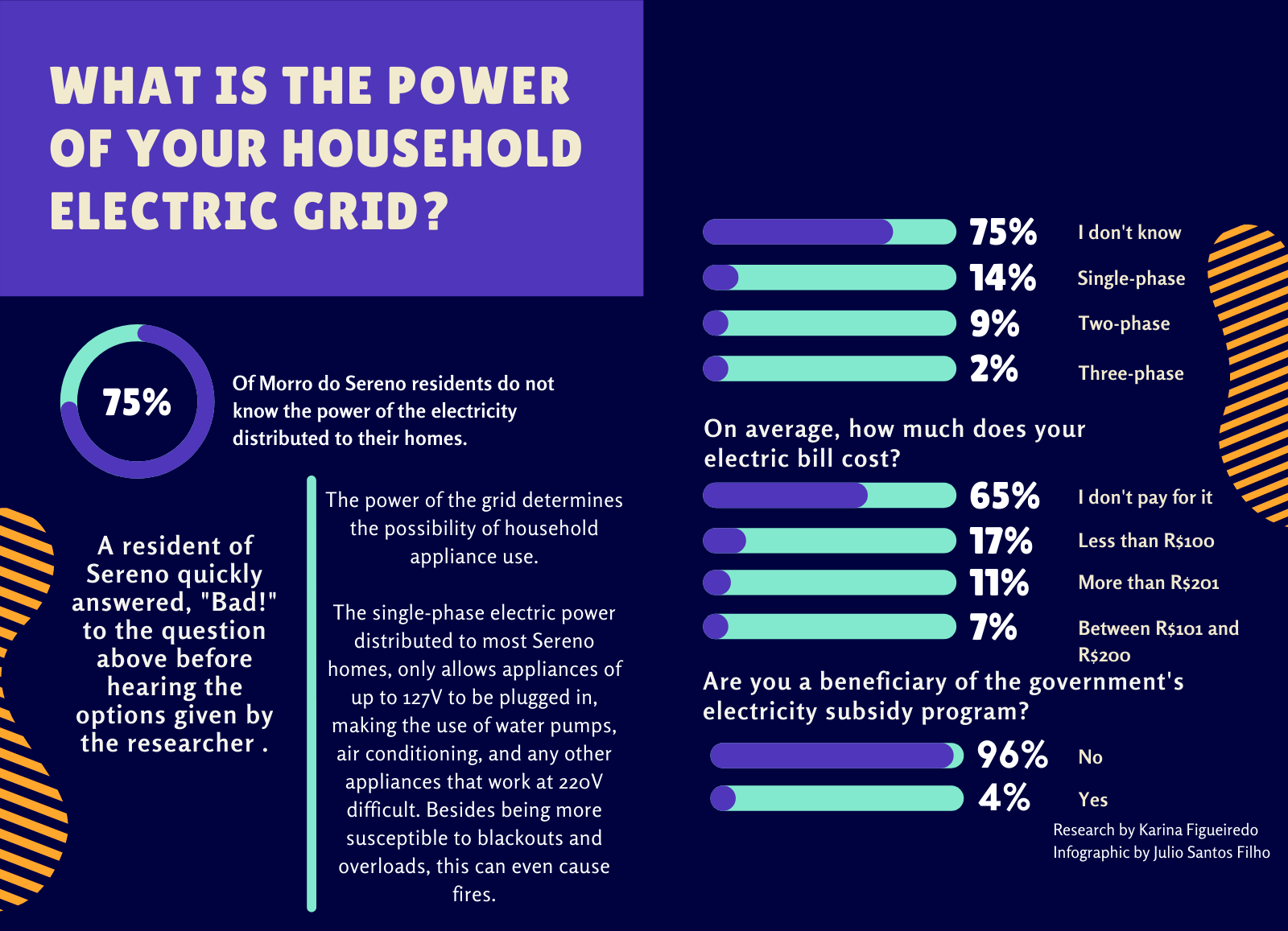

The economic pressure put on favela residents’ budgets by the costs of electricity is visible in the figures: the average income per household is R$1,359 (U$257), whereas the electric bill paid by those who have legal access to Light’s services costs, on average, is R$155 (U$29), more than 10% of the average family’s income in this area. Although electricity is not yet a social right in the Brazilian constitution, it is a right to be a beneficiary of the government’s subsidized rates. However, only 4.2% of residents say they are beneficiaries of the program.

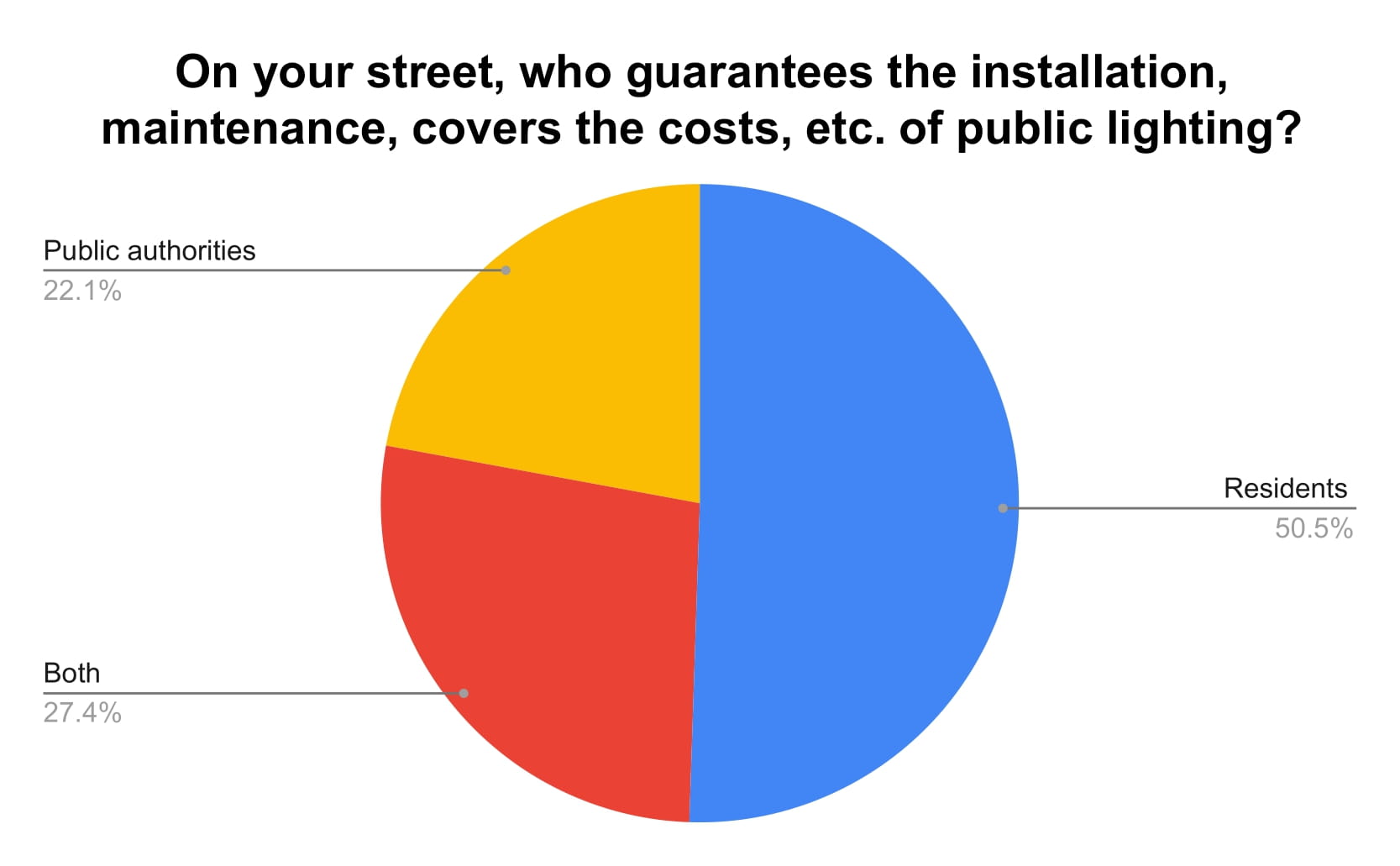

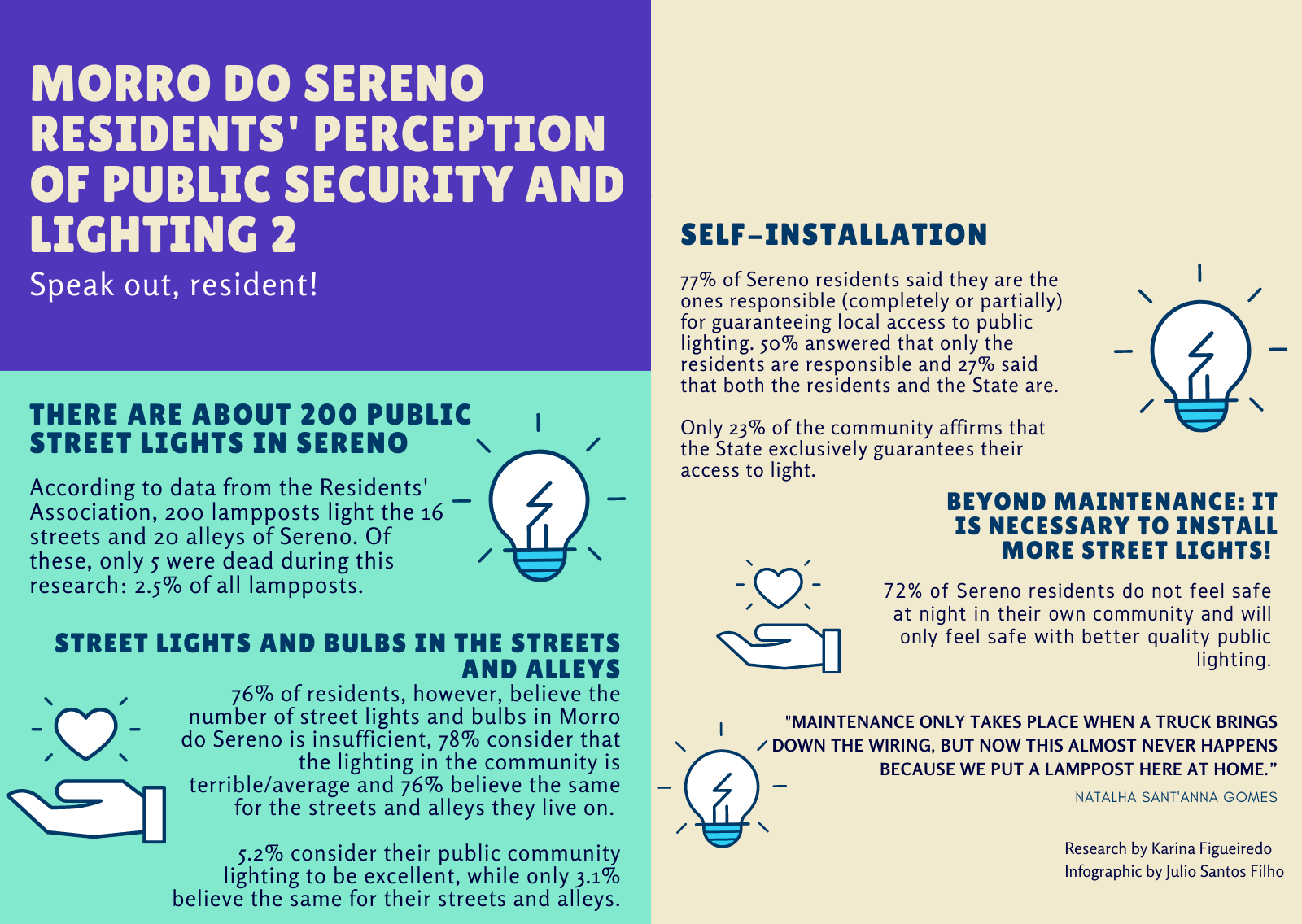

Around 34.7% have electric meters at home, through which their electricity consumption is measured by Light, paying the utility for their consumption. But the figure that most exposes the framework of distributional injustice and the burden of increasing prices is that more than 60% of the community relies on self-organization and self-installation to guarantee access to electricity—sometimes through the irregular sharing of electric meters legally fitted by the energy provider, other times through illegal hookups to poles on the street. Only 22.1% of residents told our researcher that public authorities alone are to guarantee the installation and maintenance, and cover public lighting costs on their street. Meanwhile, 50.5% said that residents do this work entirely on their own, and 27.4% said that both the State and residents look after public lampposts.

Around 34.7% have electric meters at home, through which their electricity consumption is measured by Light, paying the utility for their consumption. But the figure that most exposes the framework of distributional injustice and the burden of increasing prices is that more than 60% of the community relies on self-organization and self-installation to guarantee access to electricity—sometimes through the irregular sharing of electric meters legally fitted by the energy provider, other times through illegal hookups to poles on the street. Only 22.1% of residents told our researcher that public authorities alone are to guarantee the installation and maintenance, and cover public lighting costs on their street. Meanwhile, 50.5% said that residents do this work entirely on their own, and 27.4% said that both the State and residents look after public lampposts.

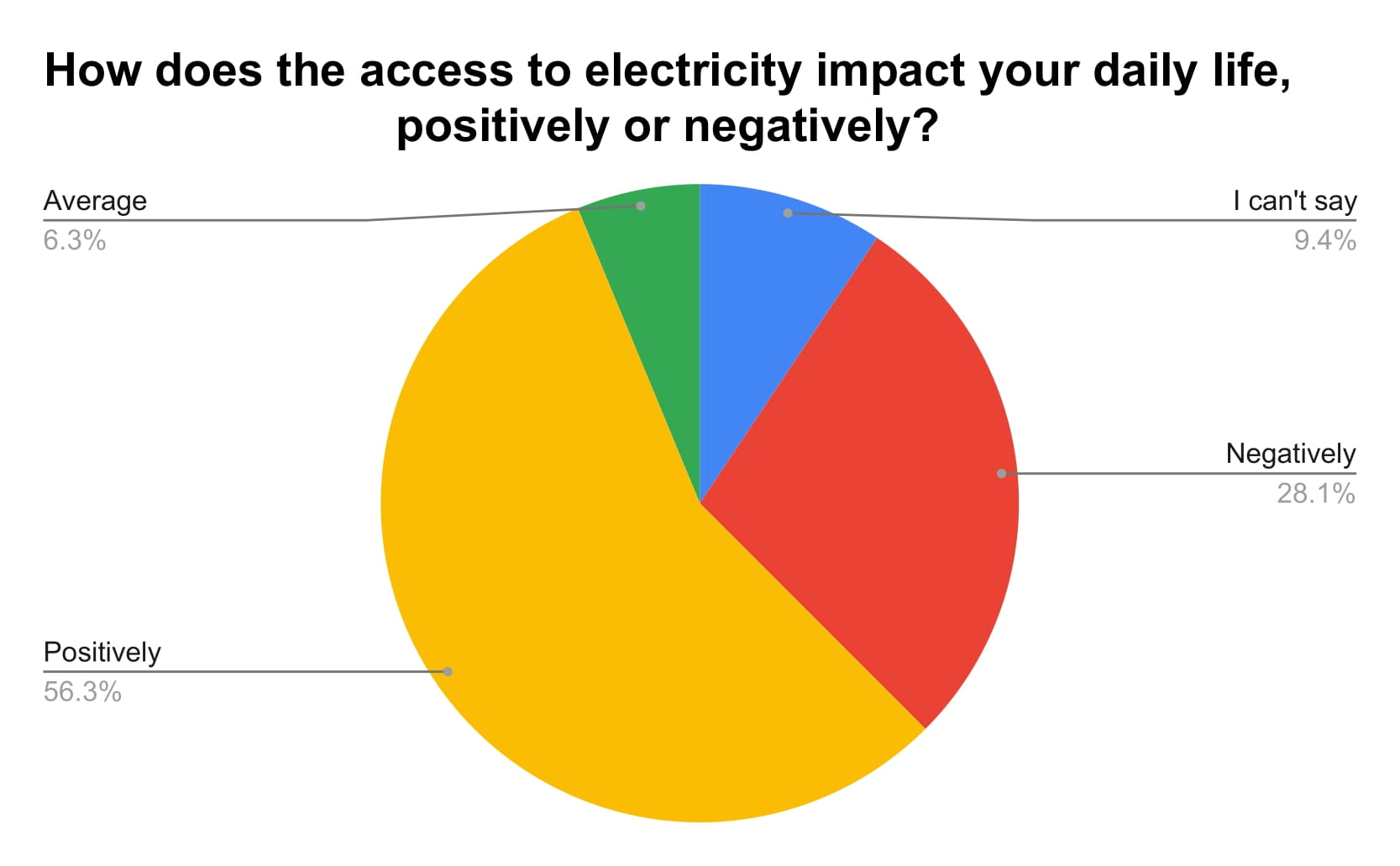

The community’s relationship with electricity is quite controversial. Despite 56.3% of Sereno saying they feel a positive impact from having electricity in their day-to-day lives, 28.1% perceive the impact of electricity supply on their daily routine as negative. Even of a dubious quality, electricity undoubtedly improves living conditions and should be guaranteed as a social right.

The research also found that 50% of interviewees felt the impacts of the pandemic on their income and stopped buying certain food products or paying for other essential services to avoid having their electricity cut off, which, as we have shown, corresponds to more than 10% of these families’ income. “[Electricity] negatively impacts my work at home. I lost a lot of merchandise. I had to throw out an entire week’s worth,” says Márcia Pereira, 42, a resident of Morro do Sereno, who as well as being a shopkeeper works as a housekeeper to increase her family’s income.

In Sereno, 43% of residents say they have already lost household appliances because of the precarious electricity service, and 57% say they cannot use their appliances as they would like, since the grid cannot cope with the houses’ energy demand, particularly in the summer.

Due to the lack of public policies aimed at expanding infrastructure (like more poles, power transformers, and meters in houses that pay subsidized rates) for a safe and legal electrical grid, the highest-up areas in the favela still only have access to single-phase power and face blackouts or electrical instability daily, preventing them from using household appliances as needed. In the highest part of the hill, on top of the connection being bad for those who have it, there are families whose homes do not have electricity and live by candlelight, a continuous reality in Rio de Janeiro.

Even the right to know what electrical power reaches homes is denied in Sereno: 75% of interviewees were unable to say if the power supply they receive at home is single-phase, two-phase, or three-phase. In the case of residents who knew what type of power supply they have, a single-phase connection is the most common. This power supply only allows for appliances of up to 127V, which makes it complicated to use water pumps, air conditioning, and any appliance that requires 220V, as they are most susceptible to power cuts and overload, which can even cause fires in wires and voltage transformers, frequent in summer.

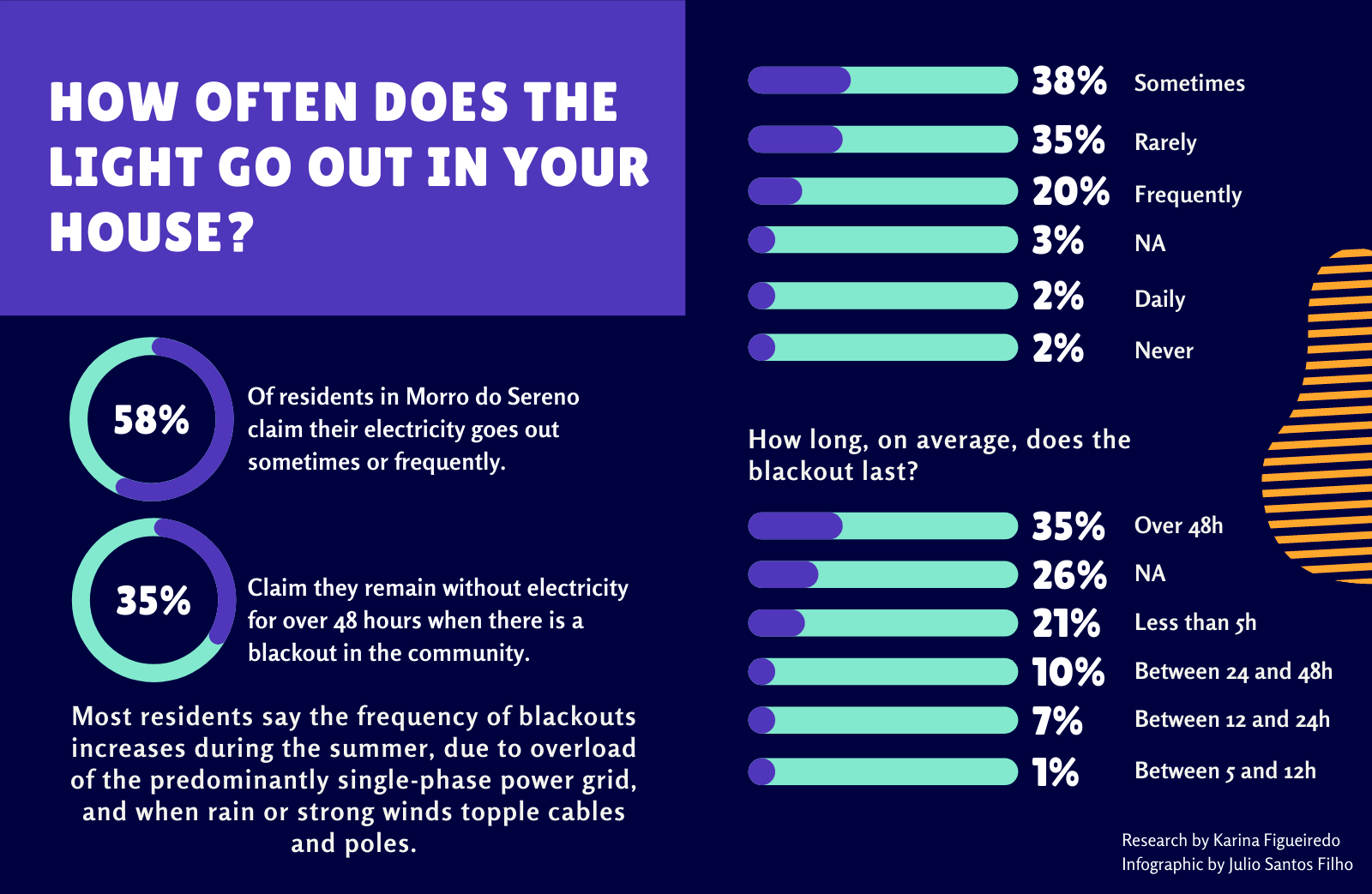

Data from the study show that 58% of residents say they find themselves without electricity sometimes or frequently, and 35% say they remain more than 48 hours without electricity when there are blackouts, this being the most frequent reply among residents. The vast majority, who do not have formal access to electricity, are left to fare alone when these problems happen in the power supply: “we depend on neighbors with legalized access to electricity to request repairs,” said one resident.

The situation of residents is rendered even more difficult by the lack of registration with the energy utility, which prevents them from requesting support for an emergency or whenever necessary. Many houses have already spent a week or more without electricity. Sabrina Pereira, 23, notes that when her house functions “at half phase,” the “[unreliable electricity] causes problems and can burn or ruin my son’s things.”

Despite 56% of respondents deeming that electricity impacts their life positively, 62% declare that Light’s service is terrible or average in Morro do Sereno. This is due to the lack of access to a reliable, legal, and financially accessible power supply. Those 35% who do have a legal electricity supply pay for services with insufficient maintenance but say they have not felt the recent increase in electricity rates in their family budget (73%).

Precarious Public Lighting and Negligence: Sereno Residents Speak of their Fears

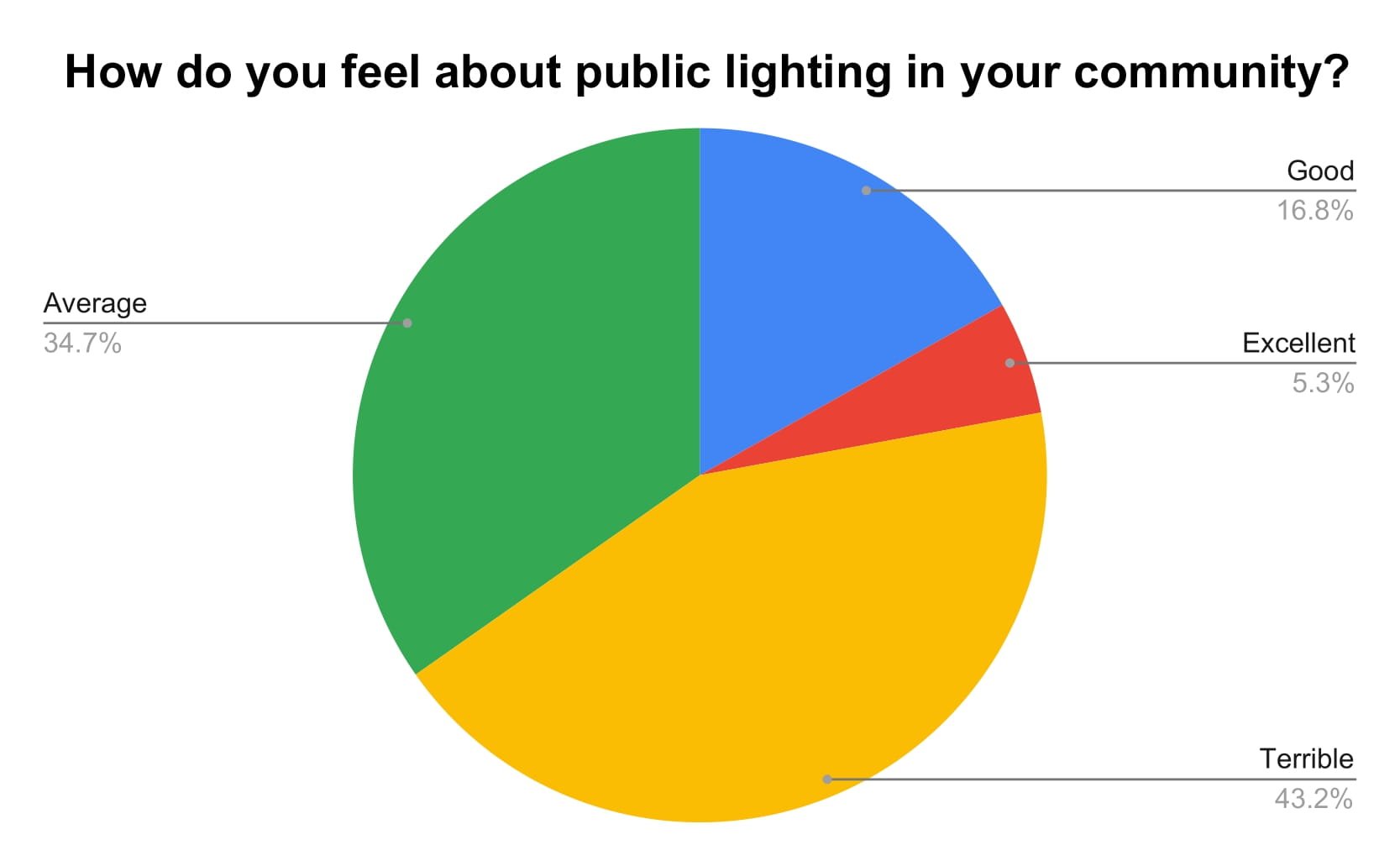

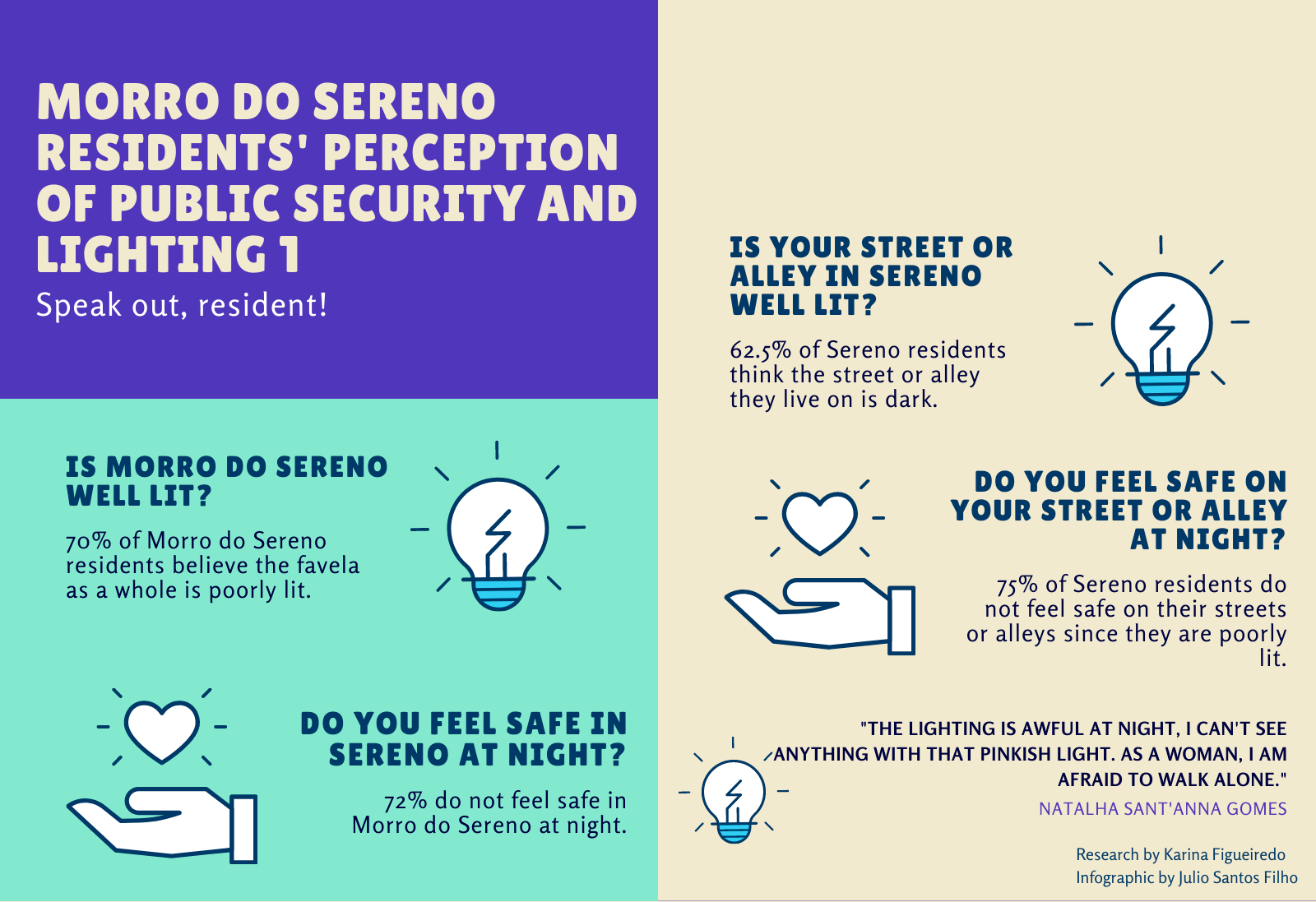

This situation of deficient access and systematic neglect in the electricity sector is also reflected in public security and a generalized sense of insecurity and fear. Throughout this study, stories abounded of people who avoided leaving home at night. Although only five of the 200 lampposts in Sereno were not working during the study—the equivalent of 2.5% of the neighborhood’s lampposts—78% believe that public lighting in the favela is terrible or average and 76% believe that the number of lampposts and light bulbs in their streets and alleys is insufficient.

This situation of deficient access and systematic neglect in the electricity sector is also reflected in public security and a generalized sense of insecurity and fear. Throughout this study, stories abounded of people who avoided leaving home at night. Although only five of the 200 lampposts in Sereno were not working during the study—the equivalent of 2.5% of the neighborhood’s lampposts—78% believe that public lighting in the favela is terrible or average and 76% believe that the number of lampposts and light bulbs in their streets and alleys is insufficient.

Walking through the neighborhood’s streets at night, it is easy to grasp the difficulty of climbing steps in darkness, broken only by the lights outside of homes, which are put in place by residents. They put up bulbs to light up the passage. This field observation also helps explain why 78% of residents consider themselves to be the only or main people responsible for the lighting on their streets and alleys. Considerations on public lighting are more or less consistent in the view of it as average or terrible: around 5.3% consider lighting to be excellent, 16.8% good, 34.7% average, and 43.2% terrible. Consequently, 70% of residents consider the neighborhood to be dark, 72% do not feel safe at night, and 75% do not feel safe on their own street or alley at night.

With insufficient public lighting, residents feel unsafe even on their own street. Despite being on their home turf, where routes are known and navigating the streets might not appear to be a problem, it is difficult to move around the streets and alleys of Sereno and of thousands of other favelas at night. This is a fear shared by the majority of interviewees, as 61.2% consider their own street or alley to be dark, 41.1% of interviewees consider public lighting on their street or alley to be average, and 34.7% terrible.

Pedro Henrique Machado, 24, a resident of Avenida Brás de Pina, one of the access roads to Morro do Sereno, was robbed on a dark street and believes that the theft was facilitated by the darkness on the street at night. He filed a police report.

Lucas Fernandes Gomes, 19, a resident of Morro da Fé, a favela which neighbors Sereno, both of which are located in Complexo da Penha, says that ten years ago, “I was going home when two men came up to rob me. But I didn’t file a police report.” Shaken and scared, he concluded: “some of the lampposts that are switched off need to be changed or more spread out to improve local lighting.”

This scenario of insecurity and energy injustice is on the radar of residents who fight daily for a better and fairer future in the face of structural difficulties. But the topic’s complexity calls for the involvement of favela residents, electricity providers, municipal authorities, and public security agencies in the search for accessible solutions to the neglect that has been imposed on favela populations for decades. In the face of this, it is necessary to think of efficient alternatives to guarantee the provision of electricity and public lighting in favelas.

A worker who wakes up at 5am or gets home at midnight depends on institutions working together to guarantee efficient changes in the area. Improvements to public lighting contribute to security and to safeguarding lives. Rather than the current “public darkness,” Morro do Sereno needs public lighting. The favela needs light!

About the author: A resident of Morro do Sereno, Karina Figueiredo is a journalist with experiences in news agencies, TV and corporate communication.

About the artist: Rafael Doria has a degree in design with a teaching license in arts. He is a designer, art teacher, illustrator, set designer, graffiti artist, artistic director, curator, and project manager.

This study was carried out with guidance from sociologist Julio Santos Filho. Infographics by Julio Santos Filho and Luiza Almeida; translation of graphs and infographics by Grant Brown and Saskia Wright.

This article is part of a series on energy justice and efficiency in Rio’s favelas.