This is the second of two articles covering the events of the 1st Sustainable Favela Network International Exchange, which took place online on August 28, 2021. Read the first part here.

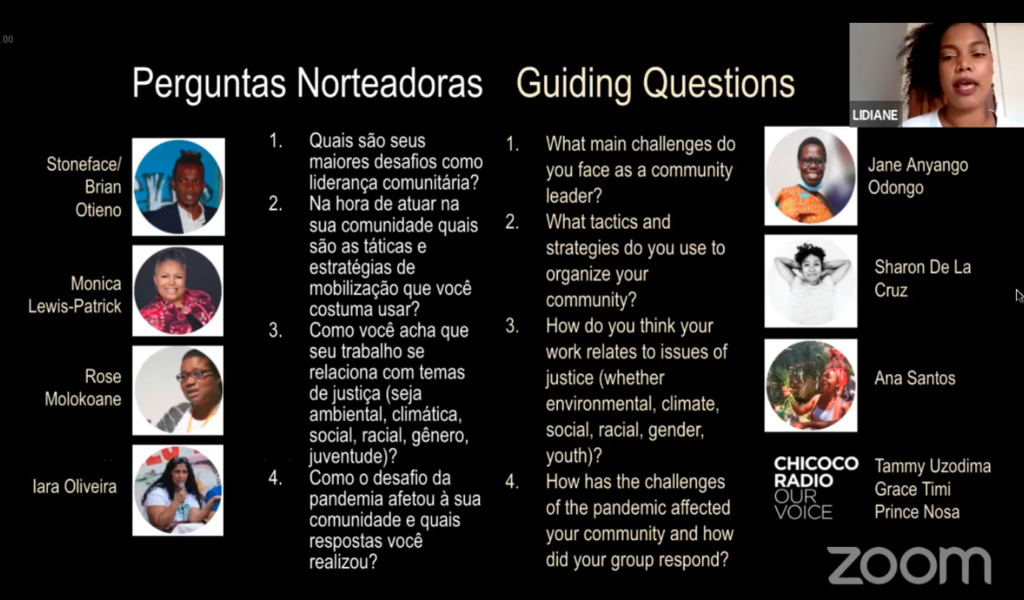

Continuing our coverage of the Sustainable Favela Network* International Exchange, which took place on August 28, 2021, this article reports on the outcomes of facilitated discussions between community organizers from informal settlements and other underserved communities in five nations, and a cultural exchange that followed. Four questions were prepared asking each participant to describe their political and cultural contexts, challenges, organizing tactics, responses to the pandemic, and how their work relates to issues of social justice.

The session’s facilitator was Lidiane Santos, from the community organization Alfazendo, based in the favela of City of God in Rio de Janeiro. Participating in the conversation were: Brian Otieno, also known by his artistic name of Stoneface Bombaa, member of the Mathare Social Justice Centre in Kenya; Jane Anyango, Kenyan activist and founder of the Polycom Development Project; Sharon De La Cruz, director of sustainability at The Point CDC, in the Bronx, New York; Iara Oliveira, founder and coordinator of Alfazendo; Prince Nosa and Grace Timi, from Chicoco Radio, in Port Harcourt, Nigeria; Rose Molokoane, coordinator of the South African Federation of the Urban Poor (FEDUP) and member of the Management Committee of Slum Dwellers International (SDI); and Ana Santos, educator from the Center for Multicultural Education (CEM) in the favelas of Complexo da Penha, Rio de Janeiro.

What main challenges do you face as a community leader?

The first question was about the challenges each faces as a community leader. Stoneface Bombaa began by describing problems faced with the police in his community of Mathare, the second largest informal settlement in Nairobi. Stoneface described how police block and hold back local actions. Jane Anyango, also from Nairobi, described conditions in Kibera, the largest informal settlement there, where she works. She described the difficulties of her work, having become a reference for women who “look up to us as a source of hope.” She personally feels sad, and the women she supports lost, when she cannot help them. “Sometimes we don’t have enough resources to help. We don’t get enough support from the government, even though we work a lot for the communities,” said Anyango.

Of the Bronx, in New York, De La Cruz responded to the same question by highlighting that “one of the main challenges exacerbated by the pandemic is the community organizing process. We all may have the greatest of intentions, but what does your process look like? [We should] think about how the process can be as inclusive as possible. Taking into account design processes that, if there is a point of contention or disagreement, can address them without things getting personal.”

What tactics and strategies do you use to organize your community?

The second question posed was on the tactics and strategies that each leader uses to organize and mobilize their community. Iara Oliveira shared that, in Alfazendo, they have learned that listening and respecting everyone is the best strategy to deal with people and to fight for rights in a participatory environment. Prince Nosa and Grace Timi said that they first try to understand what the community needs, and only then do they start planning. As a community they “use a map and we put ourselves on it to say where we come from. And this tends to tell us stories. And from these stories we start to plan,” said Nosa.

Anyango stated that, in her organization, they always try to align the work they do with existing frameworks, such as the Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda. “We also do a lot of advocacy at a community level and often collaborate with people that sympathize with the cause. We use a lot of local agents and try to make people talk a lot, so we can resonate their voices. We do a lot of lectures on the radio, show films, and pictures as well,” said Anyango.

How does your work relate to issues of justice?

How each one’s work related to issues of justice (environmental, climate, social, racial, gender, youth) was the third question asked. Ana Santos of Rio’s Center for Multicultural Integration listed the twin problems of food and climate justice, to which she and her colleagues respond by pursuing food sovereignty, water, proper housing, and agroecology. “Were it not for the By Us, For Us way of doing things, we would be much weaker in this society. This event makes me much stronger, I feel like I’m part of a much bigger network. The work is local, but the articulation is global,” said Santos. Molokoane of Slum Dwellers International also answered that they struggle a lot with land and services in South Africa, facing evictions and social violations from the government.

She added: “If we get people their rights, moral and financial support, we can work together and change problems. We need to make noise in a positive way. We need to plan for the long term, not just for the communities today. Women are not safe at all. Their children are not safe. Unemployment is huge. We are struggling to make things be done properly. If we don’t do it now, we will regret it later.”

How has the pandemic affected your community and how did your group respond?

The final question dealt with the challenges faced by their communities in responding to the pandemic. De La Cruz was the first to answer, saying that they noticed, in the Bronx, that the lack of Internet access in many homes was breaking with their children’s right to education. Ana Santos expressed that her community suffered with housing and lack of financial resources due to the government’s late response to the crisis, which resulted in people not having money to pay their rent and entering the drug traffic to earn money.

Iara Oliveira also contributed by saying that, currently, food security is a huge issue: “Without the work of grassroots organizations, a much larger number of people would have died. We were left alone, with a denialist president. With the pandemic, we started to distribute baskets of basic foodstuffs, which is not our usual objective. We were able to serve seven thousand people.” Molokoane closed the second session recounting that the pandemic blocked most of their projects, and that not being able to travel internationally harmed their movement.

Intimate Culture Circle Closes Out 1st SFN International Exchange

After a quick break, the third and final session of the exchange began. Each organization and the public were encouraged to share cultural or philosophical elements to inspire resilience in one other. Songs, poems, readings and testimonies were exchanged in a more casual dynamic, facilitated by Bruno Almeida, professor, historian and general coordinator of the Historic Orientation and Research Nucleus of Santa Cruz (NOPH), the first community ecomuseum in Brazil, and member of the Sustainable Favela Network’s Memory and Culture Working Group.

The various exchanges moved the audience by bringing emotional speeches and inspirational art. Nill Santos, founder and coordinator of the Association of Assertive Women with Social Commitment (AMAC), in Duque de Caxias, Greater Rio, drew attention to the collective power raised that day: “We get tired, and we feel alone, but it’s amazing to see that we are here together, with the same struggles. It doesn’t matter the country. We are not alone. Do you know why? We are the energy that drives and sustains this planet. I am because we are. That is what drives us.”

She was followed by Zoraide Gomes, known as Cris dos Prazeres, who manifested her passion for nature and ecology with an hopeful speech, followed by Nosa and Timi sharing the video “Somebody’s Brother” produced by Chicoco Radio and exploring police violence:

De La Cruz showed a video of the children in her community singing All I Want for Christmas is You. Ana Santos, Maria Consuelo Pereira dos Santos, Julio Fessô, Thállita Sanches, and Lidiane Santos read original texts and poems, which, together with those of other members of the public, were shared on Padlet:

The event ended with combined voices singing Rap da Felicidade (The Happiness Rap), a song that celebrates favelas, their sense of belonging, and a common wish for a better future across informal settlements:

This is the second of two articles covering the events of the 1st Sustainable Favela Network International Exchange, which took place online on August 28, 2021. Read the first part here.

*The Sustainable Favela Network and RioOnWatch are both projects of Catalytic Communities (CatComm)