The 2nd Annual Favela Community Land Trust National Seminar was held from April 18-20, 2022. The online event had 420 sign-ups from all 26 Brazilian states and the federal capital of Brasília, as well as attendees from seven other nations. Six hours of discussion and reflections on the right to housing in Brazil were held, focusing on the Favela Community Land Trust (F-CLT)* land regularization model. Residents and community leaders, researchers and students of the topic, representatives of public agencies, social movements fighting for housing, and civil society organizations were among the 240-plus live participants.

On the first day of the event, attendees were introduced to the CLT model and given an overview of international CLT experiences. On the second day, panelists discussed the difficulties of land ownership and formalization in Brazil and their impact on housing, later debating the possibilities of the CLT model. On the last day of the conference, some fundamental elements for the implementation of CLTs in Brazil were presented. Time was also spent describing the experiences of Favela-CLT pilot communities in Rio de Janeiro.

Theresa Williamson, executive director of Catalytic Communities (CatComm), welcomed conference participants and thanked the other institutions supporting the seminar: the National Forum for Urban Reform (FNRU), the Brazilian Institute of Urban Law (IBDU), FICA Fund, BR Cidades, the Center for CLT Innovation, World Habitat and UrbaMonde.

Day 1: The Right to Housing and the CLT Land Tenure Model

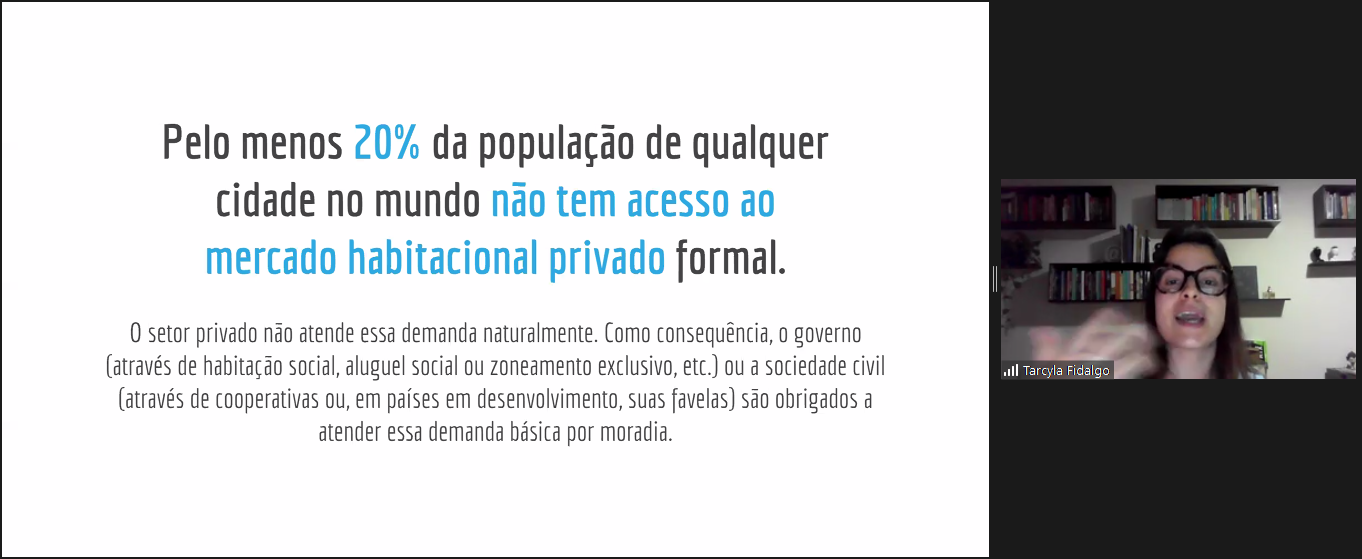

The housing situation in Brazil was the opening theme of the seminar. According to Tarcyla Fidalgo, coordinator of the Favela CLT project, “The issue of housing, the right to the city, isn’t exclusively a Brazilian problem. It’s a global issue.” One in three people in the world today live in informal settlements. “We often think of irregularity, of informality, as the exception, something that should be regulated, but this informality is in fact the norm,” indicated Fidalgo.

The private housing market is unable to solve the housing crisis, either in Brazil or abroad. This is because low-income groups cannot access this market without powerful incentive programs, policies, and public financing. For them, the only solution seems to depend on public policy, civil society support, or (as is more common) their ability to self-build. The many types of informal settlements in Brazil stem from these circumstances: that includes favelas, urban occupations, and informal allotments, among others.

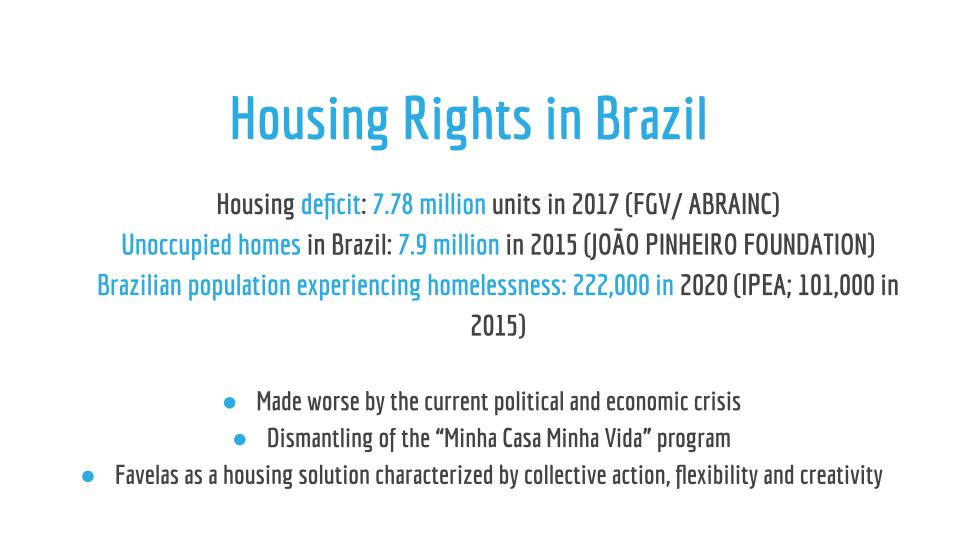

The housing deficit in Brazil is around 7.78 million units, according to 2017 data from the Getúlio Vargas Foundation. The number of unoccupied properties is slightly higher: 7.9 million, according to 2015 data from the João Pinheiro Foundation. In other words, empty homes outnumber required dwellings. To Fidalgo, this “shows that solving the housing problem in Brazil is much more political, economic, and historical than simply an issue of availability.”

In recent years, the housing crisis has worsened due to the social and economic consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. Fidalgo pointed out that the country’s housing problem has also escalated as a result of the dismantling of social programs, such as My House, My Life. This has further limited the housing prospects of low-income families, making informal settlements one of few options left for the most vulnerable groups.

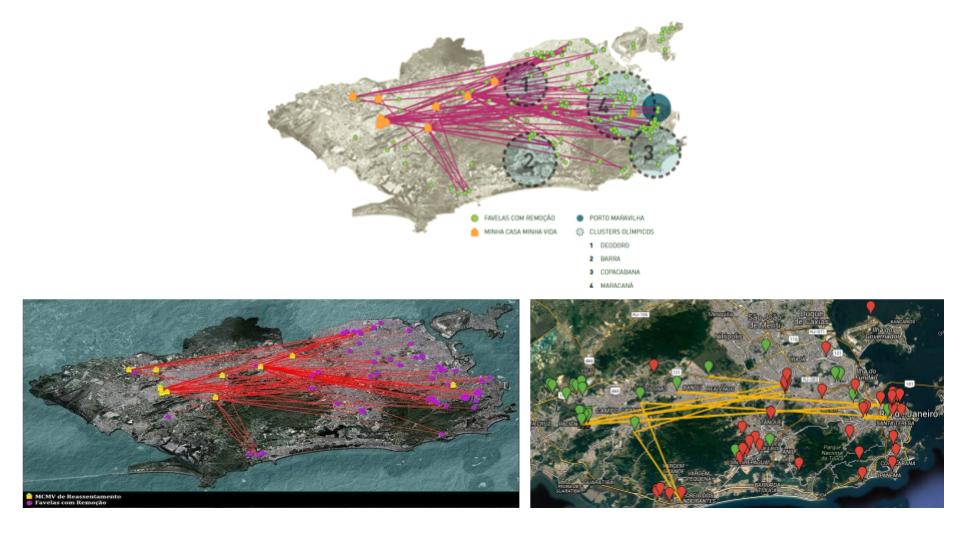

However, the Favela CLT Project coordinator concluded that building and having a home does not necessarily guarantee land security. Several tactics may deprive people of housing rights in informal settlements. These range from the violent expulsion of residents to more veiled attacks, such as buyers’ harassment and the increased costs of living in a certain region. Evictions typically take families and communities (directly or indirectly) to more remote areas of the city, with lower land values and low quality infrastructure. As a typical example of this trend, Fidalgo cited the pre-Olympic period in Rio de Janeiro, which was marked by a wave of forced evictions across the city.

At the conclusion of the first presentation, participants were divided in groups and invited to reflect on the question: “What are the greatest challenges to the right to housing and to the city in Brazil?” Challenges highlighted by participants in these groups included: housing as a commodity, the difficulty of ensuring permanence in a territory, real estate speculation, and barriers to accessing typical paths to land regularization.

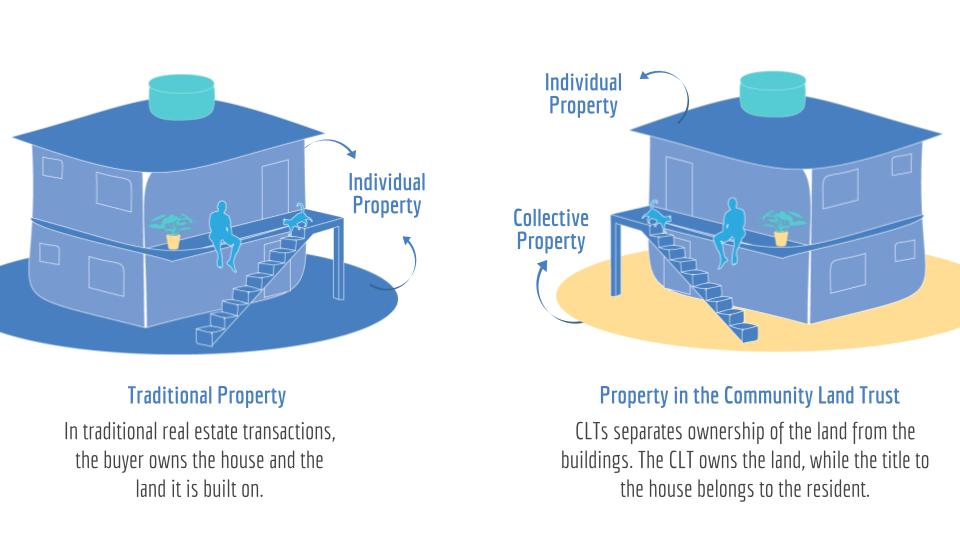

After these group discussions, Fidalgo went on to present the possibilities of land titling and regularization available in the Brazilian legal system. One unanimous concern among attendees was that land regularization and titling does not actually guarantee residents the right to remain in their territories. In fact, during the pre-Olympic period in Rio de Janeiro, communities with land titles were also forcibly removed and saw their neighborhoods gentrified. CLTs emerged in the national housing debate precisely because of this experience. Long-standing land tenure for vulnerable populations is the main objective of the CLT property model. To achieve this, the model separates land and building ownership. In CLTs, structures and their respective yards are owned by individual residents, while the land itself is communal property, belonging to a collectively established legal entity. Homeowners in CLTs may sell, rent, and transfer the title of their properties to their heirs, in accordance with rules defined by the community itself.

When buying and selling real estate in CLTs, transactions do not include the sale of land. The land belongs to the entire community, through its non-profit legal entity: it cannot be sold or given as collateral. This allows property prices to remain affordable for low-income families within a CLT. Meanwhile, the community as a whole is shielded from real estate speculation, as its land is withdrawn from the market.

“While a CLT guarantees permanence—regularizing a certain area on behalf of the community—it also ensures community empowerment to self-manage the area.” — Tarcyla Fidalgo

Currently, there are active CLTs in nations of the Global North and South, all adapted to the specific circumstances of each country. However, they all have the same common characteristics: collective land ownership, administered by a legal entity formed and managed by residents; individual home ownership, with homeowners able to sell their property in accordance with CLT-established rules; voluntary participation by members, since the CLT can only work through community engagement; community control, the community being responsible for selecting its managing council and for having a voice to directly decide on collective issues; and affordability, that is: keeping homes permanently accessible.

After this presentation, participants once again went into breakout rooms, this time to discuss the question: “What are the possibilities for CLTs in the Brazilian context? Could they help in the struggle for housing and the right to the city?” Among the main challenges pointed out were the challenges of community organizing, and fear given the novel nature of the model in Brazil.

Although unprecedented in Brazil, Fidalgo pointed out that CLTs do not need new regulatory approval to be implemented. It is already possible to create CLTs within the existing Brazilian legal framework. This potential has been recognized with the inclusion of CLTs in São João de Meriti’s master plan, in Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region, and with discussions for its inclusion in Rio de Janeiro’s master plan.

During these group discussions, attendees brought up many positive aspects of the CLT model. Its innovative character was particularly emphasized. CLTs open up new fronts and paths in the struggle for housing and the right to the city, always stemming from the position of collective community organizing. Another factor mentioned was the model’s strength in opposing real estate speculation, preventing the sale of land and its consequent transformation into a speculative asset. Similarly, attendees agreed that the CLT framework may complement other Brazilian legal instruments, such as Zones of Special Social Interest (ZEIS), land tenure regularization (ReUrbs), and surface rights. Additionally, attendees observed that the CLT model can indirectly facilitate and stimulate land regularization, ensuring residents can remain on the land after the land titling process is complete.

Conducted by CLT project assistant Felipe Litsek, the last presentation of the evening discussed CLT model experiences from around the world. Special focus was given to the Puerto Rican example of the Fideicomiso de la Tierra Caño Martín Peña, which was the first CLT organized in an informal settlement in Latin America. Litsek described it as the inspiration for the development of the CLT Project in Rio’s favelas. He also made clear how widespread this land tenure arrangement is around the world. This is especially true in the United States, where CLTs began during the civil rights movement and over 280 CLTs exist today, and in the United Kingdom, where over 300 CLTs have been established.

“The CLT model is not just about affordable housing, but also about ensuring ways for the community itself to take control of its own development.” — Felipe Litsek

Watch Day 1 of the Favela CLT National Seminar Here:

Day 2: Brazil’s Land Knot and Its Impact on the Right to Housing: New Possibilities Brought by the Community Land Trust

On the second day of the seminar, community leaders and academics discussed and answered questions from the public on “Brazil’s Land Knot and Its Impact on the Right to Housing: New Possibilities Brought by the Community Land Trust.” Five panelists, moderated by Tarcyla Fidalgo, debated the topic: Marcelo Leão from the Brazilian Institute of Urban Law (IBDU); Jurema da Silva Constâncio of the National Union for Popular Housing (UNMP); Simone Gatti of the FICA Fund and BR Cidades; Maria da Penha, housing activist from Vila Autódromo and co-founder of the Evictions Museum; and Orlando Santos Junior, from the Urban and Regional Planning Research Institute at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (IPPUR/UFRJ) and the National Forum for Urban Reform (FNRU).

Marcelo Leão, a lawyer and member of IBDU who holds a master’s degree in urban planning, history, and city architecture from the Federal University of Santa Catarina, emphasized the power of social movements in facilitating access to housing. Leão argued that progress has only been made thanks to community mobilization. “We have advanced in terms of guarantees… and in terms of the fight [for access to housing] thanks to the action of popular and community movements… the transformational power of social movements in ensuring the right to remain.” According to Leão, the view of land as a commodity is one of the major obstacles faced by social movements in guaranteeing the right to the city.

According to Jurema da Silva Constâncio, UNMP coordinator, social agent, resident, and founder of the Shangri-lá Cooperative, a successful self-managed housing initiative in Jacarepaguá, Rio de Janeiro, mobilization is the basis for guaranteeing the right to stay on one’s land. It is, in fact, the only thing capable of untying the knot of land ownership.

“I live in Jacarepaguá, in one of the most expensive areas in Rio, in a cooperative inside a favela, a collective property… This is what kept me in the housing movement: a handful of people with a lot and a lot of people with nothing… the more people on the street without a home, the better it seems to be [for real estate speculation]. Our proposal, for both the urban and rural contexts, is that everyone should have the right to housing. When we talk about the right to housing, we’re not just talking about four physical walls—it’s much more than that. It’s the right to the city, to education, and to health.” — Jurema da Silva Constâncio

Simone Gatti is an architect, urban planner, PhD and post-doctoral fellow from São Paulo University (USP), and president of the Fica Fund. She agreed that without community mobilization, gentrification and real estate speculation are able to expand freely. The Fica Fund, for example, is a civil society initiative with the mission to take properties out of the speculative real estate market and rent them at accessible rates. She highlighted that, even with collective engagement, nothing can take the place of public policy, which continues to be necessary in the fight against the housing deficit. It is important to have organized civil society engaged, including to influence the public debate on the denial of the right to housing.

Gatti, who researches rental policy and the right to remain, described the present moment as crucial for the CLT debate, especially considering the increasing rates of poverty in our cities. In this context, people will increasingly need housing policies and CLTs may be a viable alternative. She described collective land ownership as an essential power of this type of arrangement, which has the potential of truly ensuring access to property for the most economically vulnerable classes. Gatti said that she saw in New York how promising the model is.

Next to speak was Maria da Penha Macena, a resident and housing activist from Vila Autódromo and representative from the Evictions Museum, a living example of perseverance in the struggle for the right to remain in one’s territory. She reflected on the issue of land ownership in Brazil and spoke about her vision of the CLT model.

“Let’s remember that [land] is an ancient issue [in Brazil]; since the invasion by the Portuguese. And in the 21st century, despite our advances, we are still far from solving the issue. There is so much land and to have our fellow citizens living on the streets is just extremely cruel. Housing is a fundamental right, it’s for everyone. We have a hard fight ahead to achieve this and the CLT gives us a lot of hope for security of tenure. I went to New York and was introduced to the CLT there: I think it’s a tool that can really help. It will take time, but we can’t give up. It’s our right to remain in our territories.” — Maria da Penha Macena

Orlando Santos Jr., IPPUR/UFRJ professor, and researcher at the Metropolis Observatory, believes the root of the problem of working class dispossession in a segregated city like Rio de Janeiro lies in the commodification of land. During his presentation, he traced the causes and consequences of this process, which he called perverse.

“The contemporary Brazilian city is the result of two complementary mechanisms: the unchecked commodification of land and the perverse policy of tolerance for all forms of private appropriation of urban land by the elites. This occurs in parallel with the process of depriving the working class of access to decent housing in areas with good infrastructure. The result of these two mechanisms is a segregated city, where well-organized urban land is concentrated in the hands of the elites. The working class is disregarded by the market and thrown into precarious areas of the city, such as favelas and urban peripheries.” — Orlando Santos Junior

For the professor, the question of land ownership and the dynamics of growth and transformation in our cities can be summarized through two issues: democratization and distribution. The issue of democratization translates into the challenge of building active citizenship and doing away with a system that favors elite interests that govern the city. Distribution refers to breaking down the exclusionary control of access to wealth, income, and the use of urban land, which has the power to guarantee or deny access to the city as social wealth for all.

According to Santos, CLTs emerge in this context as an instrument of politicized planning for access to land, which directly addresses the two aforementioned issues. The collective management of a territory carried out by organized residents themselves presupposes grassroots participatory democracy. From the point of view of distribution, CLTs guarantee access to housing and urban land by de-commodifying land and preventing gentrification, speculation, and forced evictions. They therefore oppose the socio-political process of private appropriation of the city, contributing to solving the issue of land ownership.

After the panelists spoke, Fidalgo asked them to reflect on the role of regularization and land titling, on the post-titling process, and on how to guarantee the use of the territory for housing, access to land for the working class, and the right to remain on already-titled land. Gatti, for example, said the acquisition of a title is not the end of the process. In some cases, titling may even place the most economically vulnerable at the mercy of the speculative market. Macena argued that land should be shared and not sold.

Adding to the debate, Santos said that what in effect guarantees land tenure are a set of social, economic, and institutional factors, as well as continuous community organizing. Land regularization through individual titling alone does not guarantee the right to remain. Sometimes it protects the residents, sometimes it doesn’t. Regularization certainly changes, to some extent, the terms of exchange between people and public or market agents. But it can also be a trap, which, without other factors, transforms land and housing into a financial asset, a commodity that can be easily appropriated by big business.

After the panelists’ comments, the floor was opened to the audience for comments and questions. An impactful comment was shared by Iara Oliveira, a long-time activist from City of God and founder of the community NGO Alfazendo. Another was given by Alessandro Barros, an activist from the National Movement for the Fight for Housing (MNLM) from the city of Marituba, Pará, in the north of Brazil.

Oliveira recalled the construction of the Yellow Line, an expressway that cut through her community in the 1990s. She described it as a dramatic period of forced evictions, but thanks to the residents having the titles to their homes, the community was able to negotiate the value of their property with authorities. This ensured that residents got better compensation from the government.

Barros brought up another instrument discussed and used in his region of Pará, comparing it to the CLT model: collective adverse possession. According to Barros, collective adverse possession, which some communities in small municipalities in his area have been discussing with housing movements, takes years, sometimes even decades, to be granted by the judiciary. This is due to the difficulty and delay in producing documentation that proves ownership for the regularization of areas. He mentioned the case of a community in the city of Vigia de Nazaré, Pará: the 380 families who live there have been trying to resolve these legal issues, which might give them some legal security and ownership over their territory, for 15 years.

“So, establishing this debate around the CLT can be a viable solution for both organizing [the community] and land security. Transforming land into a collective good is what appeals to me the most. Here, in Pará… in the metropolitan area, our main problem is real estate speculation, which is very present. Outside this region we have communities interested in establishing a home, in leaving something as an inheritance for their children and grandchildren. But what type of instrument can be used to give them some kind of legal security? For housing as well as land?” — Alessandro Barros

After Barros’s comments, the second night of discussions came to an end. Felipe Litsek invited all those present to attend the next day’s sessions on how to implement a CLT in Brazil in accordance with the current legal system.

Watch Day 2 of the Favela CLT National Seminar Here:

Day 3: How to Put a CLT into Practice in Brazil?

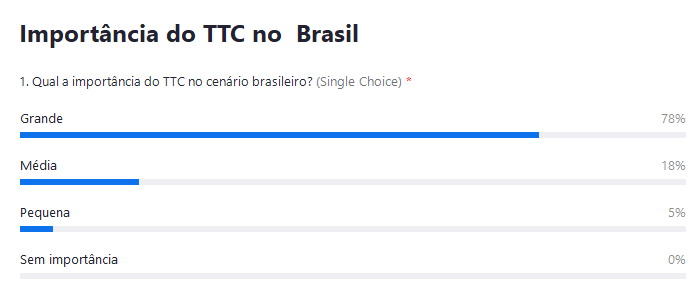

On the third day of the event, participants got acquainted with the set of elements and processes necessary for the implementation of Community Land Trusts in the Brazilian context. Those present were invited to reflect and participate in a poll on “what is the importance of CLTs in the Brazilian housing context?” Most of those present answered that they were of great or medium importance—78% and 18%, respectively.

Tarcyla Fidalgo recalled that the Favela-CLT is a Brazilian adaptation of a model that has firmly established itself around the world after emerging during the US Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. “At that time, the United States was dealing with a very complicated issue and black rural communities were being forcibly evicted. At the same time, people did not have the means to acquire land individually. They therefore started to think of a form of collective property, so they could guarantee their permanence in their territories,” said Fidalgo.

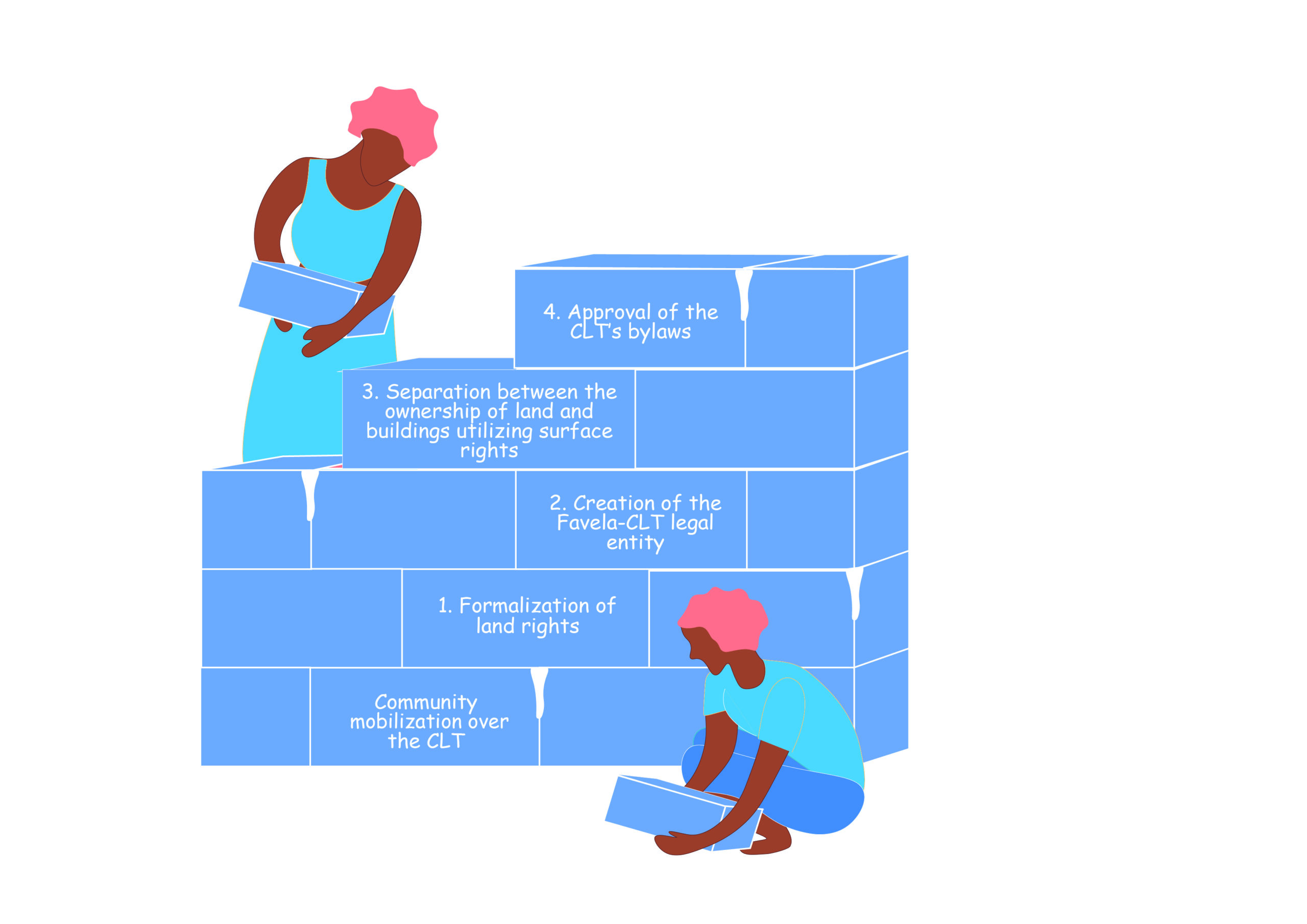

For the model to be implemented in Brazil, four pillars must be built concurrently. All depend on previous community organizing around the CLT:

- Land regularization and titling;

- The creation of a legal entity;

- The separation of the house (the individual property of the resident) and the land (the collective property of the CLT);

- The creation of an internal set of rules and regulations (bylaws), set by the community and applied in the management of the CLT.

Each one of the implementing phases of a CLT happens concurrently and always with the community heading the process. The model’s first pillar is the regularization of property ownership: a CLT can only be formalized when residents’ property is legally recognized. “CLTs cannot become official in informal housing situations… communities should start organizing while this regularization process is underway,” Fidalgo said.

The second pillar is the creation of a legal entity, a civil society organization aimed at managing the CLT’s land collectively. This legal entity can take different forms, such as an association or a cooperative, managing the territory through a council composed of residents. The management council, however, does not replace the direct participation of residents. On the contrary, the CLT managing body must always ensure the direct participation of residents.

The third pillar for implementation is the separation between the house, which is the individual property of the resident, and the land, which is the collective property of the CLT. The formalization of this division is made possible by surface rights. “Surface rights have the same legal status as property rights,” explained the TTC Project coordinator.

The fourth pillar for the development of a CLT is the set of internal regulations, or bylaws, established by residents. “As long as they adhere to all the legislation that affects that territory, these rules are pretty much open to what the community deems most appropriate. The residents have to define the best type of development for their territory,” emphasized Fidalgo.

The Favela-CLT first began in Brazil during a series of workshops held in 2018 with representatives from the Puerto Rican CLT. “Shortly after these workshops, we formed a working group that has grown to include over 200 people,” said Fidalgo. This group includes favela residents and leaders, social movement activists, researchers, and technicians from public agencies and civil society organizations. “Once we formed this group, we started thinking about pilot communities.” Initially, two pilot communities were chosen: Trapicheiros, in Tijuca, North Zone of Rio, and Conjunto Esperança, in the Jacarepaguá region, in the West Zone.

Recently, Vila Autódromo, in Barra da Tijuca, was also included in the CLT project’s work plan in Rio de Janeiro. The community went through an intense process of forced evictions in the pre-Olympic period and endures today with only 20 families living next to the Olympic Park, an area of enormous real estate interest. A fourth community is also intended to be included in the project: Jacarepaguá’s Shangri-lá Cooperative. Fidalgo highlighted that in every one of these experiences various activities and conversations are held with the community to reflect on the positive and negative aspects of a model like the CLT for their specific situations.

In addition to working with the four pilot communities, Fidalgo described how, during the pandemic, the project’s team began to think and act in order to spread the model across the country. During this period, the team also participated in several public hearings in front of the Rio de Janeiro City Council: “We are acting with the government to guarantee the CLT as a tool for urban policy.” Fidalgo ended by explaining the inclusion of the CLT in Rio de Janeiro’s Master Plan. “Being in a master plan brings legitimacy, a recognition that strengthens the model.”

After the presentation, participants were divided into breakout rooms and invited to reflect on the challenges and the potentialities of implementing the CLT model in Brazil. The possibility of complementarity between CLTs and other regularization instruments that already exist in Brazil was highlighted among the positive points. The democratizing character of access to land, which grants more autonomy to communities, was also mentioned as a plus. Maintaining community engagement, managing internal conflicts, and a possible cooptation of the collective were mentioned as the instrument’s biggest challenges.

Between potentialities and challenges, 75% of those present said they believed it was possible to implement the CLT model in Brazil. Another 15% said they found it very likely and 9% thought it would be difficult. “We strongly believe that, at the very least, CLTs are a model that need to be known. We need to spread information about them, to make sure that people know about them so they can decide for themselves whether to invest in the model,” Fidalgo concluded.

Watch Day 3 of the Favela CLT National Seminar Here:

*Both RioOnWatch and the Favela Community Land Trust (F-CLT) Project are initiatives of the NGO Catalytic Communities (CatComm).