Clique aqui para Português

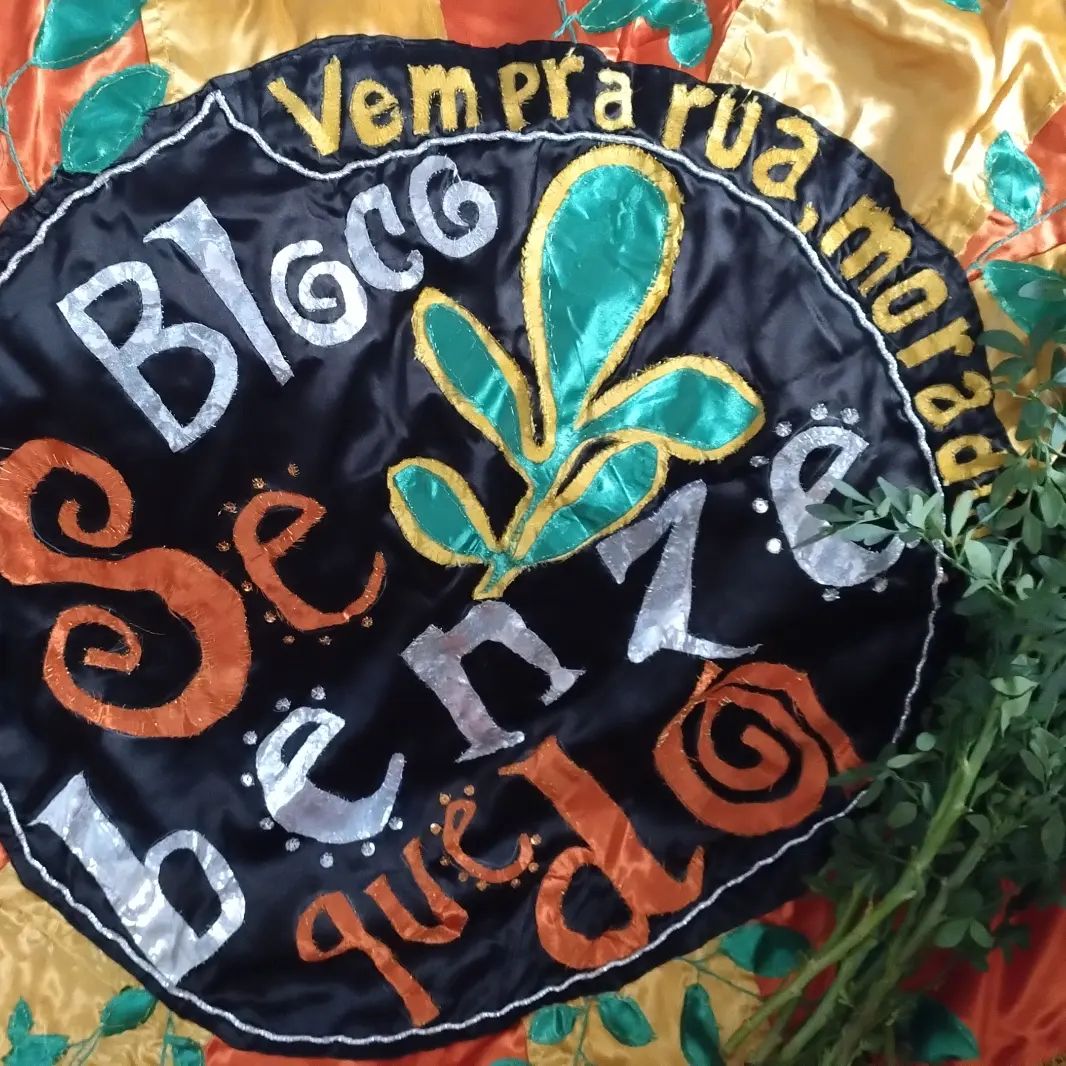

This is the third in a series of three articles about carnival traditions in Rio’s favelas and peripheries, respectively: the Bate-Bola clowns, an indelible tradition in the North and West Zones, and Greater Rio’s Baixada Fluminense region; the Bronze and Silver Series access groups, mostly samba schools from favelas; and Bloco Se Benze Que Dá (SBQD), a street carnival parade from Complexo da Maré. The three represent the unequal and disparate Rios that persist in (re)existing within a single city in the form of art and glitter.

Away from the spotlights of the Marquês de Sapucaí Sambadrome, the carnival of the favelas and peripheries reveals the strength of community work as a builder of the festivity. In this scenario of contrasts, residents of the favelas and peripheries of the city’s Metropolitan Region are responsible for safeguarding the traditions and popular culture of carnival. Whether out of love, passion, or activism, no one gives up on taking carnival to the streets, even with few resources.

19 Years of Struggle and Resistance in Maré’s Carnival

For 19 years, the Bloco Se Benze Que Dá (SBQD)—or in a loose translation that is testament to the group’s faith in better days: Bless Yourself and Go street carnival parade—has been inviting the residents of the 16 favelas of Complexo da Maré, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, home to over 140,000 people, to take to the streets without fear and enjoy carnival. Its procession serves as a form of protest and disruption. Flávia Cândido, a member of SBQD, emphasizes that “the Bloco Se Benze Que Dá is a resistance movement of individuals who started very young, but even now, as they have grown up, are always striving to involve the youth. We realized, when producing this year’s storyline, that in the 19 years of the bloco‘s existence, the word ‘hardship’ is always in the lyrics of our samba.” This characteristic is maintained in the Maré group’s 2024 samba:

“We stand strong, resilient, bold,

it’s him, it’s us, our story told,

The heartbeat of the favela’s beat,

with faith and struggle, never defeat,

thirty years of resilience and axé we show,

breaking barriers, watch us grow,

here in Maré, our unity flows.”

With over 47,000 households, according to data from the Maré Census—conducted by Redes da Maré, in partnership with Observatório de Favelas—Maré has existed for over 80 years. Since 1994, it has been officially recognized as a neighborhood in the North Zone through Municipal Law No. 2,119/1994, a fact celebrated in the bloco‘s 2024 samba:

“Join Maré’s sway,

30 years of fiery play,

freedom to come and go, our decree,

in our veins, tradition’s key.

Breaking barriers we rise,

reviving joy under skies.

You may try to quiet our call,

(Stand firm or fall),

Se Benze Que Dá stands tall.”

This 2024 carnival cry highlights the Right to the Favela and goes beyond by denouncing that the recognition of Maré as a neighborhood did not translate into improvements to the residents’ quality of life.

“To talk about the 30 years of the Maré neighborhood is to talk about a State that stops itself from functioning. We have been oppressed for many years, with the State conducting police operations and preventing schools and health centers from functioning, preventing culture from existing. Our right to come and go is taken away.” — Flávia Cândido

In Flávia Cândido’s opinion, the bloco keeps alive “not only popular culture through revelry but it also amplifies the voice of the people and their resilience during the carnival festivities.” Born and raised in Maré, Cândido now serves as a parliamentary advisor and teaches Portuguese Language and Literatures at the Studying to Succeed Community College Exam Prep Course. She highlights that the establishment of the Maré neighborhood failed to bring about equal access to the city and dignity for its residents.

“I’m part of a generation of Maré residents who used to have bus routes from Maré to Centro, to Bonsucesso, and to the South Zone, directly to PUC. But, over these 30 years, our complaint has been about how much we have lost the right to claim the city and be a part of Rio. This is very complex because the State comes in with its armed wing, but not with quality of life… The remaining buses, besides being scarce, are already overcrowded when they pass us on Avenida Brasil, the main access route to Maré, which gets completely flooded on rainy days… Our right to move around the city is denied as if Maré were not part of the city… It has been a neighborhood for 30 years, but only due to the resilience of its residents… There are streets here that only have a name and zip code today because residents who are part of NGOs developed technologies and fought for this citizenship. These dignities are taken away and the carnival bloco reclaims them. It protests, and brings all of this to light, but it does so with the power of joy.” — Flávia Cândido

“Se Benze Que Dá: Come to the Streets, Residents!” With this call and handfuls of rue—which Brazilians believe to have cleansing and protecting powers—, carnival bloco Se Benze Que Dá has opened carnival in Maré every year for almost two decades.

Made up of residents—and non-residents—of Maré, the bloco grabs attention wherever its procession goes. SBQD revelers, called Sebenzeiros and Sebenzeiras, are true champions of a community communication movement that not only reclaims street carnival in Maré but also preserves popular culture, using revelry as social critique in an unequal city.

“People get curious, they want to be a part of it, and join the parade. So they pick up the samba lyrics, and minutes later, they start to sing, following the bloco. We pass through barbecues, sing ‘happy birthday’ to revelers who are celebrating their birthdays right there on the street… we get around!” — Alexandre Dias, born and raised in Maré and a history teacher

A Carnival that Crosses Borders

Generally, it’s difficult for outsiders to understand life in Maré. However, for residents—especially youth—crossing the “borders” between the 16 favelas that make up the Complex is neither easy nor an everyday task.

That is why overcoming these barriers with the bloco‘s parade has consistently stood as a primary goal, as explained by researcher, photographer, and bloco member Fábio Caffé. For him, SBQD is integral to Maré’s community fabric, rallying residents to revel in the streets, alleys, and lanes, thereby transforming carnival joy into a catalyst for political empowerment.

“The bloco contributes to the strengthening and fostering of social bonds among Maré residents, whether they are the organizers of the party or attendees. The Sebenzeiros and Sebenzeiras have a strong connection to Maré. For them, more than a passing place, the location is deeply connected to their life stories, affections, daily routines, pains, and joys. Everything is deeply connected to the streets, alleys, lanes, and rooftops of the area.” — Fábio Caffé

For Fábio Caffé, the bloco‘s existence serves as a powerful affirmation of popular culture’s role as a tool of resistance. Despite facing numerous forms of oppression firsthand, SBQD persists in parading. “We distribute the samba-enredo to residents on the sidewalk, crash birthday celebrations unfolding in the alleys and lanes, energize barbecues as we pass by, and encourage residents peering out from their windows to join us on the street. These moments exemplify a genuine sense of community,” he emphasizes.

Established in 2005 by a group of Maré residents, including Marielle Franco, the bloco‘s parade takes place every year on two Saturdays, one before and one after carnival, spanning across various territories of Maré. The bloco manages to break down both imaginary and real barriers within the community.

SBQD has, in a certain sense, evolved into a political movement with samba-enredos that, over 19 years, document the problems faced in the favelas of Maré.

“There have been sambas addressing forced evictions, the PAC [Growth Acceleration Program], dengue fever, the oppression of police armored vehicles (‘caveirão’), the arrest of [former governor] Sérgio Cabral, and, of course, the brutal loss of Marielle Franco… Speaking about Marielle has become a central theme of the carnival bloco since her assassination, over these five years.” — Alexandre Dias

Parliamentarian Renata Souza, born and raised in Maré, SBQD reveler, and Ph.D. in Communication and Culture from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), argued in her thesis The Common and the Street: Youth resistance to the militarization of life in Maré that:

“Community experiences centered on the appropriation of the street, such as funk, the Rock em Movimento group, the Se Benze que Dá carnival bloco, the Na Favela film club, the Sarau da Roça, and the Maré 0800 street market, reveal the commitment of Black and favela youth to changing paradigms, to a molecular revolution attentive to social relations, which subvert established powers stemming from the desire for freedom. All this is done through celebration, through being together, strengthening bonds of solidarity, carnivalizing their reality, and practicing everyday resistance for survival.” — Renata Souza

The organization of the Se Benze Que Dá carnival takes place in a community-oriented way. Tasks are divided and samba lyrics are built together through a WhatsApp group. For the composition of the 2024 samba-enredo, the group also gathered in a bar in Conjunto Esperança.

“Our meeting was difficult because [it rained a lot and], when it rains, the whole of Maré gets flooded… but [the meeting] happened and the bloco will parade once again” — Flávia Cândido

In the 2024 carnival, the bloco has already taken to the streets of Maré on Saturday, February 3, and will parade for the second time on February 17.

This is the third in a series of three articles about carnival traditions in Rio’s favelas and peripheries

About the author: Tatiana Lima is a journalist, popular communicator and journalism coordinator of the Fala Roça favela newspaper from Rocinha. She has a masters degree in Media and Everyday Life from the Fluminense Federal University (UFF) where she is currently working on a PhD in Communication. A member of Complexo do Alemão’s Researchers in Movement Study Group, she also teaches reporting techniques at the Grassroots Communication Course of Núcleo Piratininga de Comunicação (NPC). A Black feminist born and raised in Favela do Quitungo and Morro do Tuiuti, Lima currently lives in Rio’s urban periphery.