On Tuesday, October 28, Brazil’s deadliest police operation resulted in over 120 people dead, leaving bodies behind wherever they fell, strewn for neighbors and families to retrieve, in the Alemão and Penha favela complexes of Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone. Rather than seeking to understand the distress and fear this generated across the city, the media narrative and public security debate quickly morphed into a struggle over public opinion. In this exchange, superficial opinion polls—all funded by unknown sources—took over the debate.

State Violence, 2026 Election, and the Power of Polling

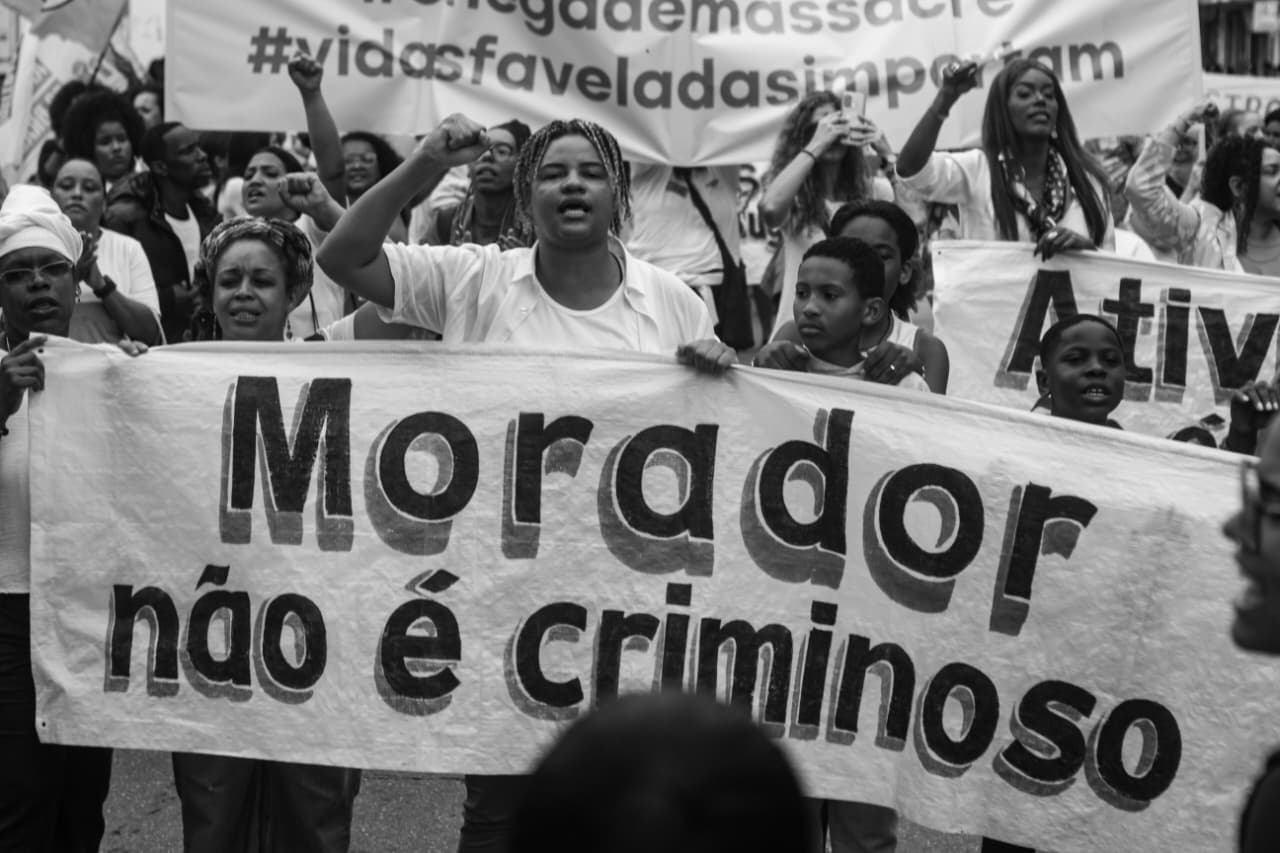

In the face of such terrible human carnage, Governor Cláudio Castro of Rio de Janeiro congratulated his administration for the operation, which he called a success. “The only victims were the four police officers killed,” he claimed, characterizing other casualties as merely “dead criminals.” Hundreds of human rights groups, social movements and local residents’ associations across Brazil denounced the police incursion as nothing short of a massacre.

Ver esta publicação no Instagram

These starkly contrasting interpretations have been reflected in media coverage of the event, which has often included graphic images of rows of—sometimes mutilated—corpses and grieving relatives with little respect for the sensibilities of families, friends and neighbors of those affected.

This reflects a familiar dilemma as it is often perceived by Rio natives: either to support violent police operations that blatantly trample on human rights, or the everyday reality of organized crime restricting residents’ rights in countless neighborhoods. It’s this problematic dualism that helps explain why aggressive operations apparently remain popular among a significant slice of citizens.

In the days since the tragedy, right-wing state governors—and even some left-wing ones—moved quickly to transform it into a political rallying point. Castro, alongside his conservative counterparts (Romeu Zema of Minas Gerais, Tarcísio de Freitas of São Paulo, Ronaldo Caiado of Goiás, and Jorginho Mello of Santa Catarina), announced the formation of a “shadow security cabinet” to coordinate efforts against organized crime, focused initially on Rio. Likewise, congressional leaders have promised to reinvigorate efforts to promote long-stalled security proposals.

The subtext to this flurry of activity appears to be to portray the increasingly popular federal administration of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—perhaps especially given its potential to consolidate popularity in passing a new law strengthening efforts against criminal groups—as passive and unprepared in the face of violent crime. Having lost battles over national sovereignty and tax justice, Brazil’s right appears poised to center the issue of public security prior to the 2026 general elections. Fear of crime and violence is a very effective wedge issue among potentially uncommitted voters.

It is in this context that mainstream Brazilian media attention has shifted from the astonishing number of fatalities to the nature of public opinion in the aftermath of the raid. Being attuned to—and influencing—the nature of public opinion, and having the ability to represent it as favorable, even despite the barbarity, is crucial to the agenda of Brazil’s extreme right.

Note to readers: as we analyze the lightning-speed opinion polls that have taken place in the past week, it is critical to note that in Brazil non-electoral polls are not required to register their clients. That is, we do not know who paid for these surveys…

Opinion Seeking Versus Opinion Shaping

In the week following the police operation, at least four separate firms conducted public opinion polls regarding popular perception of the police incursion in Alemão and Penha. It’s unknown who commissioned these surveys, but the results feed into the growing right-wing political discourse around public security and have reached different audiences in a variety of ways.

The four polls employed different methodologies, in particular with regard to forms of data collection.

The Datafolha poll interviewed 626 residents of the Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region by telephone on October 30-31. It recorded a margin of error of four percentage points and affirmed 57% thought the operation was successful, 48% believed it was well-executed, and over 80% believed that most if not all of those killed were criminals.

Ver esta publicação no Instagram

Atlas Intelligence (AtlasIntel) conducted a poll of adult residents of Rio de Janeiro who were randomly recruited to complete an online survey by responding to a banner ad. The survey was conducted on October 29-30 with 1,527 respondents and a margin of error of three percentage points. It concludes that, in the city of Rio, 62.2% approve of the operation and 80% of Rio’s favela residents support the operation (while only 51% of those outside favelas approve).

AtlasIntel also conducted a survey with the same questions placed to a national sample (broken down by the country’s five geographical regions rather than by state) and subsequently published a comparison report of the two surveys, which indicated a more negative reaction towards Rio’s police actions nationally than locally.

Ver esta publicação no Instagram

A Paraná Pesquisas study was based on in-person interviews with 800 residents of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro on October 30, recording a margin of error of 3.5 percentage points. The sample was selected from across the city proportionally to population size and subsequently according to demographic variables. This study concluded that 69.6% of Rio locals support the operations.

Ver esta publicação no Instagram

Finally, Genial Investments/Quaest conducted surveys at the homes of 1,500 residents of the State of Rio de Janeiro (over the age of 16) on October 30-31, with half through oral, half written questionnaire. The respondents were selected from 40 municipalities proportional to size and demographic characteristics. The margin of error was estimated at three percentage points. It states that 64% of Rio State residents approve of the operation.

Ver esta publicação no Instagram

All four studies concluded that a solid majority of those surveyed approved of the police activity in Alemão and Penha, although they reported varying levels of support.

Ver esta publicação no Instagram

Most coverage of the surveys focused on the findings of general support for the police action, making that the headline, without delving much into findings, sharing only basic methodological details such as sample size and margins of error.

While the theme of public acquiescence characterized most treatments, very few news pieces reported this opinion research more thoroughly. O Globo’s treatment of the data from the Genial/Quaest survey entered into more detail, describing how “the incident did not change residents’ perception of security and amplified the feeling that the state is living in a ‘war-like atmosphere’.”

All reports failed to discuss the potential limitations of extrapolating on a complex topic from polls with such limited and superficial questions.

Ver esta publicação no Instagram

Why Polling Methodology—and Reader Scrutiny—Matters

One of the first questions regarding the representativeness or accuracy of survey or poll research data is the issue of sample size. Opinion research is conducted via samples because it is impossible to study the entire population in the time span an opinion study requires. Conclusions drawn from samples are intended to be reliably generalized to the population.

Of concern here is the AtlasIntel survey whose findings were extrapolated to make claims about the opinions of Rio’s favela residents themselves (rather than the city’s population as a whole). What was the sample size for this particular population (and for different categories of respondents in general)? What about the diversity of favelas and their inhabitants: where they are located in the city, how close or distant they are from the police operation, if and what armed group currently controls them—beyond trafficking factions, there are vigilante police militias that are widely known to control public opinion and behavior, and that control more favelas than drug traffickers.

Research in and on favelas is complex and hence why even the national census fails to accurately reflect these areas. Residents—especially those at lower income levels within their communities—suffer from energy and Internet access issues, Internet literacy issues, and are chronically over-worked. Who are the “half dozen” favela residents interviewed and how can they be expected to represent 1.4 million people?

This is yet another manifestation of a longstanding problem: the exclusion and generalization of voices from peripheral communities in public discourse and civic debate. Mainstream media outlets have historically painted favelas with crude brushstrokes, falling back on traditional stereotypes in ways that delegitimize or obscure the diverse and complex concerns and opinions of favela residents.

Those who lack reliable access to the Internet or do so primarily through apps on their phone (rather than via a web browser’s landing page) are less likely to be exposed to banner ads for polls and, in the age of IP geolocation, very unlikely to respond to a time-consuming survey soliciting potentially jeopardizing opinions about the actions of the police in their communities.

The combination of a reliance on historical stereotypes and simplifications and the use of methodologies that are blind to the realities of favela lives means that favela opinions simply cannot be ascertained from this survey, and attempting to do so is irresponsible.

Some of these polls were conducted by phone during the last two days of October. The numbers were either randomly generated—like spam marketing calls—or based on publicly available subscriber registration data. What groups have the time (and inclination) to answer a fairly long list of questions about relatively sensitive issues over the phone to a stranger (or an AI-generated interlocutor)?

In both developed and developing countries around the world, response rates for polling have been increasingly unreliable—as famously reflected in the accuracy of political polling in recent years. For this reason, pollsters have attempted to come up with more statistically viable means to apprehend survey subjects. One employed here, “Random Digital Recruitment” [RDR], is a proprietary methodology developed by AtlasIntel with the aim of creating robust samples that are more representative of the target population. It provides a means to gather survey respondents online by targeting users based on their web browsing behavior and demographics. This approach aims to ensure a representative sample by adjusting for non-response bias and demographic variables. RDR has a reputation in the industry for election result prediction. It was ranked by industry observers as the most accurate pollster of the 2020 United States presidential election and accurately predicted electoral results in various Latin American countries. That said, election polling is very different from opinion polling. And RDR strategies produce more reliable data when based on large national samples rather than smaller samples at the urban level.

Sensationalism May Sell, but Neither Educates, Nor Informs

The issue here is not the poll results, but how such oversimplified questions—useful in an election survey but useless in understanding widespread opinion on such a complex issue as public security—contribute to misinformation and the fears that underly the very subject, especially when reported on without critical interpretation.

The world’s largest Portuguese-speaking portal, UOL, reported survey data on the raid on its own site and various social media platforms. Particularly egregious was its lurid and sensational coverage of the AtlasIntel survey just discussed. UOL promoted its multi-slide coverage of AtlasIntel’s poll results with an initial image of a row of dead victims’ corpses—almost all partially naked young Black men—surrounded by grieving relatives and friends. Superimposed on this horrific image was the statement that “87.6% of Rio’s favela residents approve of the mega-operation.”

Only on the very last slide (of 16), itself superimposed over the image of a bloody hand protruding from a shroud, was it noted that the results were the product of online interviews of 1,527 residents of Rio de Janeiro. It is not evident from the published survey results what number (or indeed percentage) of these respondents were living in favelas. So, while the 87.6% figure may be eye-catching, as explained above, it is effectively useless.

It’s not clear if the UOL coverage was an attempt to shape public opinion around the growing public security debate or just a callous attempt at clickbait; either way, it is not primarily about sharing helpful information—as journalism is supposed to be—and did little to elucidate AtlasIntel’s research results, much less Rio citizens’ fears and concerns around the state of public security. And this is only one case amid a myriad of poorly reported news pieces on the October 28 Penha and Alemão massacre and the 121 assassinated by the police forces.