Irenaldo Honório da Silva, president of the Pica-Pau Residents’ Association, is at a loss. The small favela where he has led community organizing efforts for over twenty years, slightly north of Maré along Avenida Brasil, has in the past eighteen months witnessed robust commitments to what will be the first large-scale public upgrades in its history, those from the municipal Morar Carioca program. Teams of architects, technical surveyors, and social scientists have visited, noting the locations of abandoned buildings that could be converted into schools and health centers and asking residents what they envision for the community to be better served. The original deadline for the construction plans to be finalized was mid-2012 for Pica-Pau and 88 other favelas across the city. In May 2013, none of these favelas have drawings finalized, and surveying for the 129 other favelas scheduled to have plans finalized by the end of 2013 has not begun.

When Pica-Pau was selected for Morar Carioca in 2011, Irenaldo was told that it was because the North Zone community, sandwiched between the Ciadade Alta housing project and a mucky stretch of the Irajá River, had for so long existed outside the reach of public resources. (This fact has by no means muffled grassroots improvements in the community; one example is the car-tires-turned-tree-planters linining the river.) Despite this, Irenaldo is having difficulty getting reliable information from the city government about when–and if–the community will receive upgrades at all.

Pica-Pau’s Timeline as a Phase II Morar Carioca Site

In July 2010, Rio mayor Eduardo Paes announced the city plan to “urbanize all the favelas in Rio by 2020,” by way of Morar Carioca, as part of Rio’s Olympic Legacy. In October 2012, the guidelines for the Morar Carioca program were signed into City Decree with a guarantee of the right to “participation of organized society…in all stages of Morar Carioca through assemblies and meetings in the communities” and through the “presentation of works and debates open to the participation of civil society and citizens.”

In order to meet its obligation to guarantee community participation (which was not done in the dozens of communities that have received unparticipatory interventions retroactively labeled ‘Morar Carioca Phase I’) the City government contracted the nonprofit iBase, which works to promote “active citizenship,” conducting surveys and focus groups in communities to incorporate resident perspectives and desires into designs.

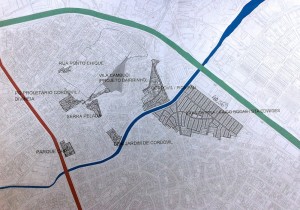

Participatory upgrades are planned for 218 favelas as part of the authentic Morar Carioca program, also called “Phase II” of Morar Carioca. Pica-Pau’s group–Group 16, which includes the rest of Cordovil and Brás de Pina–was one of the eleven groups chosen for the first round of funding, surveying, and construction. iBase was contracted to conduct participatory surveys for Pica-Pau on April 27, 2011. Morar Carioca signs were erected throughout the community. Through mid- to late-2012, the Group 16 architecture firm, Arquos, which had in the past conducted favela upgrades in nearby Penha, surveyed the area with the help of an engineering team, and iBase conducted participatory workshops.

Suddenly, in January 2013, iBase staffers stopped doing their door-to-door survey work. The following month, the Morar Carioca signs were taken down from Pica-Pau.

At the beginning of March, confused about what was going on, representatives from the Residents’ Associations of Brás de Pina, Adivinea/Parque Proletário de Cordovil, and Pica-Pau, requested a meeting with the city government. On March 9, Maria Eugenia Carmo, who had been responsible for surveying the community for home and building ownership, met with them as a representative of Morar Carioca.

Carmo brought with her two maps produced by the architecture team for the area. One showed the seven favelas included in Group 16. The other showed, in addition to these, locations of abandoned or little-used buildings in the area that would make good candidates for the installation of schools, health centers, and daycares. “My job is hard, because the mayor is a crazy visionary,” said Eugenia, “There are so many things he wants to do. But he really does want to do something here in Cordovil.”

The four community leaders present–Irenaldo, Eduardo Oliveira de Matos, Shirlei Felix Santiago, and Janete Faria de Oliveira–said theirs were committed communities who would use the proposed public works well. Over 4000 residents had already enrolled in digital literacy courses despite low public investment in the area; residents had to go all the way to Penha for access to a public library.

“There will be Morar Carioca works here in, at the maximum, two years,” said Eugenia.

Positive Steps for Participation

At their office in downtown Rio, an hour and a half from Cordovil, iBase surveyors who worked on the project say the participatory processes they had begun to facilitate in Cordovil were what truly differentiated Morar Carioca from past upgrading programs.

“The idea behind Morar Carioca was very exciting to us. It was to really build off the lessons learned from programs in the past such as the Favela-Bairro program and the PAC,” said Sergio Azevedo, the iBase Social Diagnostic Coordinator for Morar Carioca. “In those programs, sometimes residents were given a chance to say their opinions about what was happening, but those opinions were rarely incorporated into the plans.” Prior processes constituted a form of tokenism, not full participation.

Robson Rezende, the iBase field coordinator for Morar Carioca Group 16, said that iBase facilitated three different activities in Cordovil. The first was the “memory workshop,” in which oral histories were gathered about the origins of the community from older residents. Some of them described the founding of the community in 1965 and the fact that people moved there from the northeast and from the favela of Praia do Pinto in the South Zone, which burned down in 1969 after the community had resisted removal three times under governor Negrão de Lima.

Secondly, iBase conducted focus groups of different kinds of residents, such as young people, the elderly, and business owners. In these, not only residents from the favela but also residents of the surrounding area participated. Rezende said, “Morar Carioca believed ideologically in something that iBase has been saying for years: that there is not a difference between the favelas and the city. Favelas are part of the city. In order to understand how they function within the city as a whole, you need to talk to neighbors from outside and understand which spaces in the city as a whole the residents use–because that’s going to be much larger than the area of the favela itself. For example, it is important for many residents of Cordovil to have access to the Madureira market for shopping, and many work in the Cemetery of Caju,” down Avenida Brasil.

“Another important element of these focal groups was allowing people small enough forums that they will feel comfortable giving honest opinions; that is, separating average residents from community leaders so they are speaking for themselves rather than having someone else speak for them,” said Rezende. “Doing this you can gain additional insights. For example, for three years, on paper, there had been free technical training courses offered for residents at a nearby center called Senac, but it came up in the focus groups that no one would go to these sessions because they had not heard about them.” The iBase team then noted that inter-community communication channels was an important issue to address.

According to the focus groups, said Rezende, “the public sector was really not present” in the areas of the Group 16 favelas because although there had been works to install a water network and a daycare, “these were not preserved in good quality. They were functioning like something designed for third-class citizens.” This came in addition to issues that iBase had anticipated hearing about such as open sewerage, broken pavement, and inadequate public lighting.

The final activity that iBase facilitated was the “dreams workshop” in which residents gave their specific suggestions for public works. iBase used the results of all three of these activities to advise the Macrodiagnostic and Microdiagnostic Reports on Group 16, made together with the architecture firm. The following step would have been for the firm to present their recommendations to the community and for the community to give feedback in an activity called the “Roda de Diálogo” (Dialogue Circle). Then the “Intervention Plan” would be finalized by the architects, together with the “Integration Plan” for socially connecting the favelas with the surrounding areas.

The Roda de Diálogo occurred in a few of the eleven initial groups of favelas to receive Morar Carioca such as Jardim America and Barreira do Vasco. But it did not occur in Pica-Pau; the architects and iBase have been waiting for months for the city government to release funding for them to proceed.

The Pica-Pau architects’ plans are ready for the Roda de Dialogo. Jonas Goudinho of Arquos is extremely proud of them; he incorporated the perspectives from the iBase surveys to address the issues of access to transportation, health, and education resources. He has calculated the reach of existing schools and health centers based not on their capacity but on what physical obstacles–the river, highways, and housing projects–block residents from arriving quickly. Based on this new calculation, he has indicated both places where a new daycare should be built and places where bridges and pedestrian space should be constructed. It even falls within the Morar Carioca architects’ prerogative to suggest re-routing of local bus routes, and Goudinho has suggestions for this as well.

Goudinho, like the iBase team, was excited to participate in Morar Carioca in an effort to innovate based on the lessons of past upgrades. A graduate of an elementary and high school in Rio’s Santa Teresa neighborhood, he did volunteer work in the nearby favela of Prazeres and became an architect with the hope of working on design issues in favelas in a professional capacity. Goudinho said of the Arquos plans for Group 16 what Rezende said of iBase’s surveys: “We believe very strongly in what we did there.”

The Waiting Game

After iBase’s contract with the Rio de Janeiro city government was cancelled on November 28, 2012, they continued surveying activities on their own budget. But in early February, with funds shrinking and no visible commitment from the city to supporting continuation of the Morar Carioca activities in Cordovil, they ended their fieldwork and sent a letter, pictured at right, to all residents who had participated.

The letter thanked participants and explained the circumstances surrounding the premature end of iBase’s work. It noted, “We consider a program like Morar Carioca an advance in public policy as it considers the favela a form of the city, and we believe only active monitoring done by favela residents will make the program something that respects the right to a more just, democratic, and sustainable Rio de Janeiro for everyone. This is a priority for iBase that has accompanied urban interventions in Rio over the long term, always defending the rights of favela populations and other marginalized groups and facilitating their participation.”

Rezende, in an interview, brought up again the importance of developing citizen dialogue surrounding urban interventions as a long-term process. Because of this, he said that cutting off participatory planning activities with no restart date was “very bad. The months start to go by,” he said. “The residents don’t hear anything.” He shook his head.

Rezende said some perspective could be gained by taking note of when the Morar Carioca activities were occurring in fullest force across the city: August, September, and October 2012, the months running up to the Rio de Janeiro mayoral election.

For the past few months, he has heard more silence than anything else.

Rezende said the degree to which citizens unified and brainstormed solutions for Cordovil was empowering in itself, especially because several residents spoke up who never thought they had anything to contribute to community planning before this point. The iBase letter emphasizes this accomplishment and expresses hope that its momentum will guide planning in Cordovil in the future. “iBase is still rooting for the success of Morar Carioca,” the letter finishes. Representatives both of iBase and of Arquos have encouraged Cordovil community leaders to continue lobbying for the arrival of Morar Carioca works.

In the Pica-Pau Residents’ Association headquarters, Irenaldo is trying to schedule another meeting with a representative of the city government. “We just want to know if we should expect public works,” he says. “If so, when should we expect them? This year? Next year? I know the architects have drawn a set of plans that are ready right now.”