For the original by Andressa Cabral in Portuguese on Viva Favela click here.

It took 14 years to execute, with 140 favelas and allotments benefitting from US$600 million in investment. Twenty years after the municipal favela upgrading program Favela-Bairro began being implemented, what can be seen today is proof that such works alone aren’t enough to integrate the favelas into the city. “The major challenge is carrying out maintenance on the developments, which is expensive. Introduced services like garbage collection, water, sewerage and electricity are eventually no longer maintained,” says Pedro da Luz, one of the architects responsible for the development of the program.

Over the years, many obstacles stood in the way of Favela-Bairro’s continuation. The communities kept growing, works were delayed, the program lost investors and construction for the Pan-American Games in 2007 became the government’s priority. In 2008 the program came to an end, the same year that would see the end of Mayor Cesar Maia’s mandate. From then, new government housing projects such as the federal government’s Minha Casa Minha Vida and the municipal government’s Morar Carioca started to appear.

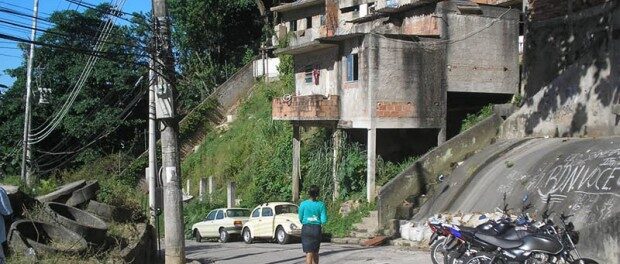

In the favelas visited by Viva Favela that were part of Favela-Bairro, the problems encountered are practically the same: lack of maintenance, problems in sewer lines and garbage collection. Each, however, has its particularities.

History of the Program

“Favela–Bairro” was developed between 1993 and 1995 by the Rio de Janeiro city government (during Mayor Cesar Maia’s mandate) together with the Federal University of Rio’s School of Architecture and Urbanism (FAU-UFRJ), the Brazilian Institute of Architects (IAB-RJ) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). In each of the two phases of Favela-Bairro (1994-2000 and 2000-2007), the IDB invested US$180 million and the Rio city government US$120 million.

The program received an award at Expo 2000, in Hannover, Germany, and is considered a model project by the United Nations. According to the Municipal Housing Secretariat, 500,000 people benefitted.

The project began to be elaborated after the Constitution of 1988 determined that cities with over 20,000 inhabitants should have a Master Plan. In 1992, the Rio de Janeiro Master Plan was established and determined, among other measures, that favelas should obtain characteristics of formal regulated neighborhoods such as services and quality infrastructure. Based on Decree 12,994 of 16/06/1994, the Favela-Bairro project would be applied in large favelas (“Grandes Favelas”), medium sized favelas (“Favela–Bairro”) and small favelas (“Bairrinho”).

Morro de Babilônia (Leme)

Part of the “Bairrinho” category of the project (devoted to smaller favelas), Babilônia completed sewerage and road widening works in 2003. However, due to the bankruptcy of the contractor responsible for the project in the same year, many of the works were left unfinished, such as the expansion of the water tank, the installation of energy and water networks and the construction of a housing complex–which nonetheless received residents removed from areas of high risk or environmental protection.

According to Carlos Pereira, president of the Residents and Friends of Babilônia Association, the organs responsible did not contact the community after the works were paralyzed in 2003. The unfinished water reservation tank has become a breeding ground for mosquitos carrying dengue fever and the sewage network is now insufficient for the needs of the community. Only in 2011 were the Favela-Bairro works taken up by Morar Carioca, which remain in progress.

Favela Dois de Maio (Engenho Novo)

“After Favela-Bairro, we began to be called a ‘community’ as a result of the structural improvements we received. Now we have regressed to the eighties, when we were seen as a ‘favela.’ If we remain as we are today, five years down the line we will be one of the ugliest favelas in Rio,” laments Yanui de Andrade, president of the Dois de Maio Neighborhood Association.

Having received Favela-Bairro works between 2002 and 2004, what we see today in the community in Engenho Novo, North Zone, is a precariousness of what was undertaken: channelling the Jacaré river, water and sewage, construction of a housing complex and leisure area, lighting and the widening and paving of the streets. The sewage system is already showing problems, football courts aren’t fenced and the events square is now used as a Jacarezinho Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) post. Open air sewage and garbage are part of the community scenery.

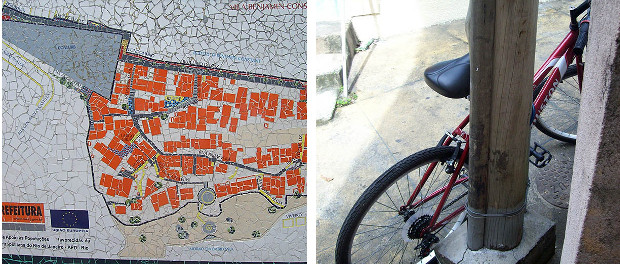

Vila Benjamin Constant (Urca)

“Vila was defined as the most organized community in Rio de Janeiro’s Bairrinho project. Nice title, but at the end of the day it contributed nothing in relation to the improvement and maintenance post-program. That never happened,” Luis Fernando Lima emphatically affirmed, president of the Vila Benjamin Constant Neighborhood Association.

The works were carried out from 1999 to 2001 and since then, small maintenance falls into the hands of the residents. Favela-Bairro initially brought paving, sanitation, organization of house numbers and improvements to water and electricity networks. Since then, the works have fallen into disrepair: wooden posts are rotten, sewage pipes are clogged and toys in the playground facilities are damaged and rusty.

Jardim Moriçaba (Senador Vasconcelos)

This district in the West Zone received works on its water and sewerage systems, the opening and paving of streets, channelling of the Cabuçu Mirim river, improvements in lighting and the construction of housing, childcare and leisure areas. Favela-Bairro ended up happening in 2 phases there: 1999 to 2000, when the contractor responsible for the project went bankrupt, and later from 2003-2005, when the works recommenced.

The channel, which was limited exclusively to the flow of the river, now also takes in residents’ sewage. Moreover, it never underwent dredging and is currently silted. The sewage treatment plant is abandoned and filling with water. The water tank has no back-up pump causing many residents to endure days without water when there is a technical problem with the only pump. The new streets were never named and the postal service henceforth doesn’t deliver.

“When the works were completed, there was a community street sweeper who did the cleaning. Today this service no longer exists here. There’s loads of debris piled up in the streets and when we call Comlurb [municipal waste collection company], we still hear that the community has no education,” complains Genaina Nacimento, member of the Jardim Moriçaba Neighborhood Association.