Vale Encantado, a favela in the heart of the Tijuca forest, part of the largest urban forest system in the world in the middle of the municipality of Rio de Janeiro, was used as a case study to demonstrate favelas’ potential as models of sustainable development during the international sustainable building conference GreenBuilding Brasil, held in São Paulo from August 5-7. The example of Vale Encantado was used to illustrate the potential vocation for sustainability among favelas and of sustainably upgrading informal settlements worldwide. It was also the focus of a collaborative solution-mapping charrette among participants.

In their presentation about Vale Encantado, architect Luis Felipe Vasconcellos, from RVBA Architects, city planner Theresa Williamson, from Catalytic Communities, and community organizer Otávio Barros, President of the Vale Encantado Cooperative listed and described the sustainability principles naturally present in favela communities and explored how LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) methodologies can contribute to upgrading them in both a sustainable and participatory way.

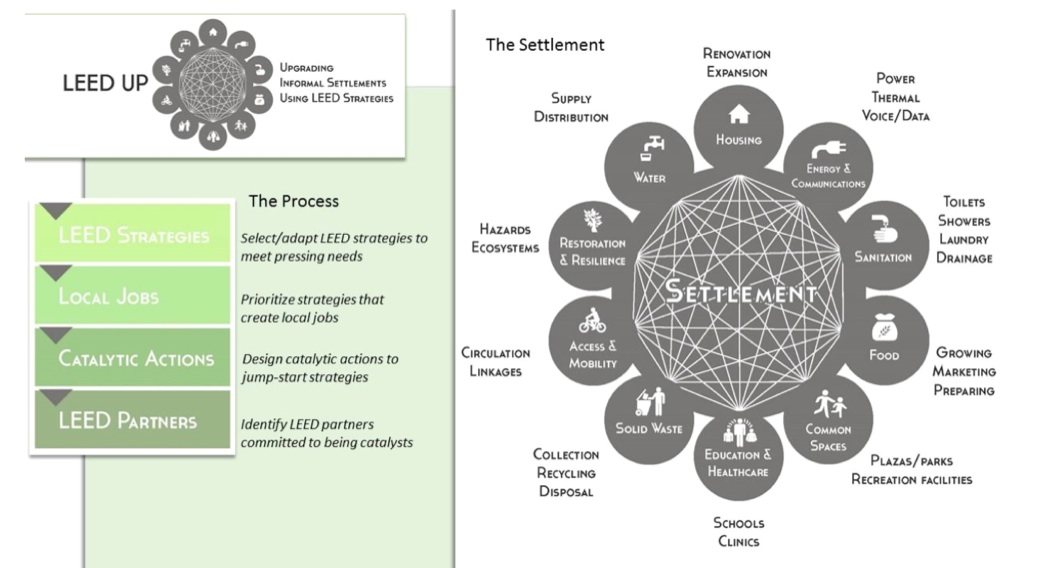

LEED is the most widely respected set of rating systems to green the design, construction and maintenance of buildings and neighborhoods. Eliot Allen, from Criterion Planners in Portland, has led global efforts to apply LEED standards to neighborhoods and is a co-creator of the now-recognized LEED for Neighborhood Development (LEED-ND) rating system. It was Allen who initiated the idea of promoting the sustainability of informal settlements through LEED, by introducing the idea of creating a rating system for sustainable participatory upgrading of informal settlements, which he coined LEED-UP (LEED for Upgrading Informal Settlements).

During her presentation, Williamson explained why favelas in Rio de Janeiro should be looked at as a source of inspiration for sustainable practices despite the stigma that exists around these settlements. The stigma associated with favelas is manifest in its four frequent English translations: “slum” which conveys the idea of absolute precariousness and misery; “shanty town,” which evokes a haphazard agglomeration of improvised wooden shacks; “squatter community,” which stigmatizes residents for the initial occupation process by which they settled; or “ghetto,” which implies they are isolated and marginalized, and wanting “out” of such communities. These terms, by encouraging stigma, render the development of these communities more difficult.

They do not reflect the reality of Rio’s favelas, where the vast majority of homes are made of brick, concrete and reinforced steel, several stories high. They are built through a process learnt over generations, as Rio de Janeiro was the birthplace of the first favela in Brazil 117 years ago. Thus, today these communities are for the most part consolidated, and many are highly functional environments. Today the city has around a thousand individual favelas. Due to the one attribute common to all favelas–a lack of regulation–they have evolved organically, and thus are all unique. The variety of experiences in just Rio’s favelas is tremendous, Williamson explains, more so when we scale up to informal settlements worldwide. They suffer from insufficient or low quality public services like sanitation and infrastructure, but in what residents can achieve on their own, they exemplify human ingenuity. Favelas are dynamic, creative and entrepreneurial places.

Urban planners have been working to emulate qualities that already exist in the favelas for decades. Favelas are low-rise / high-density environments, pedestrian and cyclist oriented, with a high use of public transportation. Favelas promote mixed use (homes above shops, for example) and historically guarantee short distances from residence to workplace. They are built through collective action and grow organically: their architecture evolves according to needs. Favelas are also a place for intricate solidarity networks and a vibrant cultural production.

Vale Encantado, which appropriately translates to Enchanted Valley in English, is a small community in the middle of the Tijuca forest. Barros described its long history whereby it has been intrinsically linked to the forest and thus developed an interest in ecology. This interest is manifest in the cooperative of the entrepreneurial community, which organizes eco-walks in the forest and showcases the local gastronomy, including the famous “jacalhau,” their version of the famous Portuguese cod, onion and potato dish using locally picked jackfruit instead of cod. An important source of Vale Encantado’s food comes from the community’s plants; they are currently recovering a garden area to produce more healthy food.

It is also piloting technical initiatives that encourage the favela’s environmental sustainability: a solar panel and a biodigester that reuses organic waste to provide gas for cooking and fertilizer for the community’s plants.

Vale Encantado is a great pilot community to become a sustainable favela model: it already has a vocation for this and its small size make achieving the status of the “first sustainable favela” mid-term viable. Given the right information and tools, it is ready to experiment local strategies that larger favelas could apply in the future.

Vale Encantado, like all favelas, suffers from a lack of infrastructure and public services. Historically, Rio’s favelas look to change this through petitioning government to meet these needs. However, even in communities where public services are eventually provided, the quality of such services is universally low and maintenance problematic. This not to mention that those services that are provided are part of the formal system, a system that–in a city where sewerage is pumped raw into the ocean, whether collected in favelas or the formal city–is often unsustainable.

It was thus explained at the conference how LEED-UP (LEED for Upgrading Informal Settlements) could upgrade favelas–providing those missing public services–in a high-quality, community-led, and sustainable way. Job creation is also intrinsic to the LEED-UP model.

As designed by Allen, LEED-UP is led by the community, with community leaders and interested residents beginning the process by identifying their priorities among those listed (housing, energy and communications, sanitation, food, common spaces, education and healthcare, solid waste, access and mobility, restoration and resilience, and water). Once priorities are defined through a participatory process, technical partners help select and adapt LEED strategies to meet these most pressing needs. They are then analyzed to see which solutions offer the greatest potential of job creation, and actions that can be taken are identified. Finally, LEED partners that can help secure the desired investments are recruited.

Following the presentation, GreenBuilding conference participants were invited to participate in a dynamic charrette around tables, with detailed maps and diagnostics of the community, and to act as consultants, drawing on their knowledge of LEED methodologies and technologies. International green building professionals discussed possible solutions and new ideas for sanitation, energy, telecommunications and leisure areas, by drawing on practices elsewhere that could be adapted to the Vale Encantado context.

They suggested creating a “living machine,” where natural processes and plants would clean wastewater. Rio de Janeiro has serious sewage treatment problems, and Vale Encantado could be an example in this domain.

They suggested a zip line and rope canopy course in the forest of Vale Encantado, a leisure space different from conventional urban playgrounds that would be unique to the community and work with its natural qualities rather than promote urban children’s infrastructure less appropriate to the location.

Suggestions were also made for better drainage, solid waste collection and energy generation systems.

In the discussion that followed, it was discovered that the community was already working towards implementing several of the project suggestions, with the charrette both offering new ideas and confirming the residents’ current path.

Francisca Rojas, Urban Development and Housing Specialist at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) in Buenos Aires, participated in the charrette. She summarized the session which she said brought her to the conference:

“The potential exists to improve quality of life in informal settlements through the introduction of more environmentally conscious, low-impact development strategies, such as green infrastructure and urban agriculture, which can improve a site’s resilience in the face of natural hazards like flooding and landslides. A great opportunity exists to rethink urban upgrading programs where conventional infrastructure, like street paving and drainage systems, can be modified to incorporate more sustainable interventions that work with natural systems like permeable paving, bioswales, rain gardens, etc. This will require a paradigm shift in the conventional upgrading model, where interventions are tailored to local conditions and residents participate actively in both the design and maintenance of the green infrastructure systems.”

Rojas explained that at the IDB, “the conversation is beginning to shift towards considering green urban development strategies in urban upgrading programs, with the hopes of carrying out pilot projects” to begin testing some of those ideas.

Williamson hopes this conference is the beginning of a conversation that sparks “an increasing recognition of the role of informal settlements in a sustainable urbanization model worldwide” and a dialogue on “how to integrate these communities by leapfrogging past big infrastructure programs to community-scale, employment-generating and empowering programs with a dramatically reduced environmental footprint.”

In 2050 a third of humanity is expected to live in informal settlements: population growth will take place in the favelas of the world, rather than in rural areas or formal parts of the city over the coming decades.

Many of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas have a long history and are well developed; there is a lot of potential for starting sustainable strategies in a place like Vale Encantado and using them as an example in Rio and across the world.