This is the second of a two-part series on Rio de Janeiro’s Port Zone.

As was seen in the first article of this series, the Port Zone has been continuously shaped by urban projects that built a city on the foundation of the exploitation of black labor and simultaneously, through governmental practices of eviction and eradication that are still present today. Throughout history, policies in the region reaffirm, time and again, that this population did and does not belong in privileged areas, even if they have come to be the Port’s primary occupants over hundreds of years. The history of the Port Zone and its black population, as much a target of removals (when classified as “invaders”) as of eradication (when classified as “criminals,” “traffickers,” etc.), can help one understand how this city marginalizes the black population, yet also uses elements of its culture as tourist attractions. After all, how does one explain a region where the African Heritage Circuit has become a major tourist attraction, yet where residents, the majority of whom are black, are removed or evicted?

In fact, for decades after attempts to whiten the city took place at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the discourse adopted by city officials and architects was still that of primarily highlighting and promoting the areas in the region that were most closely associated with European roots and Catholicism. Even after acknowledging the heritage of the Pedra do Sal Quilombo in the state of Rio de Janeiro in 1987, the Hill of Conceição (of which Pedra do Sal is a part) was continually portrayed as a little Portugal in Rio de Janeiro, and the “legitimate” and “desirable” residents were Portuguese and Spanish descendants. These definitions excluded residents from the Northeast and those who had been occupying abandoned spaces: they were seen as “undesirable” and “disposable” by the permanent residents as well as by urban planners. According to this Eurocentric history of the region, makeshift housing and tenements were unfit ways of living and their population “polluted” a “white” and “respectable” place. Later this was associated with drug traffickers, and the favela Morro da Providência.

The values or qualities associated with the different areas of the Port Zone belong, therefore, to an ideal that defines what can be modified, excluded or buried, and what must be emphasized and celebrated, according to hierarchical classifications of race, ethnicity, religion and class. This hierarchical order was made particularly clear in 2001 in the Rio Port Plan, and later in the “Porto Maravilha” port regeneration program, in which the three lines of intervention were established according to “needs” and possibilities within each area of the region. The first line of intervention outlined the attraction of the middle class and tourism to the hills of Conceição, Livramento and Pinto, which were already areas associated with a “high historic, landscape, and cultural value” since patrimonialization was done in the SAGAS project (acronym for Saúde, Gamba and Santo Cristo) in 1988.

The areas not included within this definition were not seen as carrying the same historical, landscape and cultural value, and were left for other public policies such as the second line of intervention. Reserved for Morro da Providência and for Caju, these policies, such as the Favela-Bairro program initiated in 1994, promoted a series of works to “integrate” the favela into the rest of the city. According to these policies, the areas not associated with the past and the white, middle-class population needed to be adapted to meet the standards of the “formal” city primarily through the formal introduction of utilities (such as electricity and water) that already existed informally in the favelas.

Finally, the third line of intervention recommended the conversion of the Port’s warehouses, which, in an area with one of the lowest Human Development Indices of the city, would now target civil servants earning around ten times the minimum wage or, in another proposal, families with incomes greater than three times the minimum wage.

It is important to remember that these attempts of whitening space and memory were never passively accepted by those “buried” with each urban project planned for the region. The wave of evicting occupants out of private and public buildings was challenged by claims of black memory and historical belonging by the occupants of the region. This is evident, for example, in the use of names referring to the history of black struggle in urban spaces, such as Zumbi dos Palmares, Machado de Assis, Mariana Crioula, Chiquinha Gonzaga and Quilombo das Guerreiras.

Projects to homogenize the city also met with resistance when, at the end of 2005, families facing a wave of evictions and removals by the Venerable Third Order of St. Francis of Penance (VoT) church in the Port region pleaded their right to the region as the ethnic-racial Community of Remaining Members of the Pedra do Sal Quilombo. Since then, their fight for recognition and permanence in the region has become an important symbol in recreating a “black city,” as Maurício Hora, member of the Pedra do Sal Quilombo, made clear: “Who is it that built all this? Who worked at the Port? Where was the Port where the slaves arrived? Where were these slaves sold? Where is it they were buried? Are we going to say then, that no black people lived on Conceição Hill, that no black people ever lived on those floors, that no store owner had any black workers, that no black person has worked in Pedra do Sal?”

It was only after reclamations like these, advocating on behalf of those who had built and continue to build the city with their own hands, that the Historical and Archaeological Circuit of African Heritage was set up in 2011, including the Valongo slave wharf, New Blacks Cemetery, Centro Cultural José Bonifácio, Largo do Depósito, Jardim Suspenso do Valongo and Pedra do Sal. A document that was partly responsible for the selection of the sites to be included in the circuit (Valongo Letter of Recommendations) quotes the historic attempt to “erase all traces of the black movement” in the Port Zone. The same document fails, however, to make the essential connection between the past and the present, in which black residents are still systematically evicted from the region around the circuit. Without that connection it is difficult for this memory, which has been rightfully brought back to the surface, to be used to make the changes necessary to achieve racial justice.

As stated in the Valongo Letter of Recommendations, the administration of the circuit did implement the actions relating to the circuit and also put up road signs, primarily thanks to activities promoted by various groups connected to the Black Movement in Rio de Janeiro. However, in the depictions of the explanatory mural inside the Porto Maravilha container next to the Cais do Valongo, it is still clearly evident that there is a disconnect between the exploitation of black labor and the whitening of the city, both in the past and the present. In the murals, the forced black labor that permeated the history of Pedra do Sal was supposedly replaced by samba, and the site became the place where “port laborers gathered to sing and dance.” The police’s targeting of samba groups and Candomblé (Afro-Brazilian religious) practices associated with Pedra do Sal, as well as the actual working conditions and discrimination in the lives of port laborers, are not mentioned.

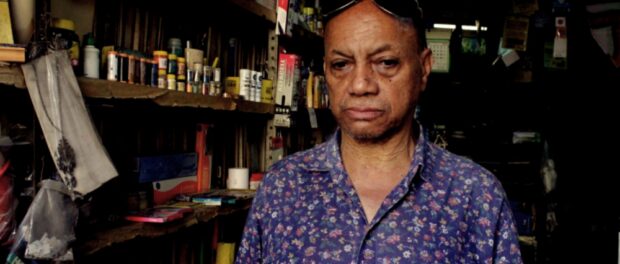

These memories are kept alive by residents like Oswaldo Almeida, a 79-year-old resident of Camerino Street. Almeida tells of how the activities of Candomblé and umbanda groups in which his mother participated had to be kept secret. According to him, the terreiros (places where sacred rites were performed) had to be “totally closed off and hidden. Nobody could make a noise, for if they did the police would come to arrest them.” Considering this alternative story, one can imagine how the song and dance of the port laborers in places such as Pedra do Sal (be it in the 19th century or the 20th century as Oswaldo remembers) faced daily repression by the police and became established as holding an important role within black cultural resistance. Without the space for these memories of the struggle and repression in the official discourse of the African Heritage Circuit, the connections that could be made between past and present day police targeting of funk parties in the “pacified” favelas of the city are ignored and the injustice repeats itself.

The absence of these alternative stories can be explained by the fact that, as the murals in the Porto Maravilha container show, the archaeological research and results are seen as a kind of “added value” to the process of revitalization which reveals “treasures” of the region’s history. It is very clear through the choice of language in the murals that projects like the African Heritage Circuit are seen as products that can and should be sold. As such, they can be manipulated to give legitimacy (“to add value”) to the regeneration process of the Port Zone, which after all, was not primarily planned to benefit the poorest population. Reserved for this population are plans of unequal integration into the city through the militarization of daily life as promoted by the Pacifying Police Units. In practice, establishing the African Heritage Circuit does not appear to have the intention of creating a more just society for black men and women, except for the moments in which the black population themselves take over the space to claim it, as happened in the celebration of the Centenary of Abdias do Nascimento in Cais do Valongo in March 2014.

It is through the acknowledgement of the fundamental omissions in the discourse concerning black memory that has been put forward by the Porto Maravilha public-private partnership that we can understand how a place as important as the New Blacks Institute and Cemetery could announce on December 3, 2014 that it would close its doors due to a lack of public support. Only after this decision was made by the family that runs the institute did representatives of the City in the region arrive with promises of substantial aid.

An urban project that makes use of black culture and history to “add value” to their undertakings, but gives little or no thought to the struggle for equality and racial justice, reveals its true purpose when one considers the luxury condominiums that are soon to be launched in the region. In a city where the three million black men and women that make up almost half of the population are relegated to the outskirts with a lower family income, it is easy to imagine who the inhabitants of these new developments will be. If in the past, it was the bodies of black people that were commodities, it seems that today it is their memory.

This is the second part of a series of two articles about the Port Zone of Rio de Janeiro.

Eduarda Araujo is from Rio de Janeiro and is a student of African Studies and the African Diapora at Brown University. She researches structural racism and black resistance in the processes of formation of urban space in Rio de Janeiro.