On Wednesday July 20, Rio-based public policy group Casa Fluminense, comprised of representatives of hundreds of civil society organizations across the state, held a workshop for journalists covering Rio de Janeiro after the Olympic Games. Speakers briefed journalists on what they see as the biggest challenges facing the city and the most important issues in the upcoming mayoral elections in October. Topics examined in Casa Fluminense’s research into urban inequality in Rio include transport and urban mobility, sanitation, pollution in the Guanabara Bay and public security.

Researchers divided Rio de Janeiro’s greater metropolitan region into three areas for their analyses: the city of Rio, the Baixada Fluminense to its north and west, and the Metropolitan East on the other side of Guanabara Bay.

The workshop was opened by economist Vitor Mihessen, who revealed that 74% of the state’s population lives in the highly urban Rio de Janeiro metropolitan region, making Rio de Janeiro “the most metropolitan of any state in Brazil.”

Mihessen’s analysis of social inequality across Rio de Janeiro state used census data including Human Development Index scores, average monthly wage, commute times, school enrollment levels, mortality rates and access to running water and trash collection as an introduction to understand how quality of life varies across the state. The sum of all of these factors, he argued, is demonstrated in average life expectancy in Rio: the statewide life expectancy is 75 years of age, but residents living in Quiemados or Seropédica in the Baixada Fluminense live, on average, two years less than those in Rio city.

“We have to make this comparison so we can see how [not broadening our view to] the metropolis can be a problem,” said Mihessen. “It’s also interesting from a public policy point of view.”

Clarisse Linke, researcher from the Brazilian Institute of Transport and Development Policy, spoke about transport as a major challenge for Rio state in the coming years. Average monthly wages throughout the state contribute to the picture of a varying quality of life depending on geographical location, with Rio city inhabitants’ average monthly salary of R$2,216 starkly contrasting the R$624 of those in Japeri in the Baixada Fluminense.

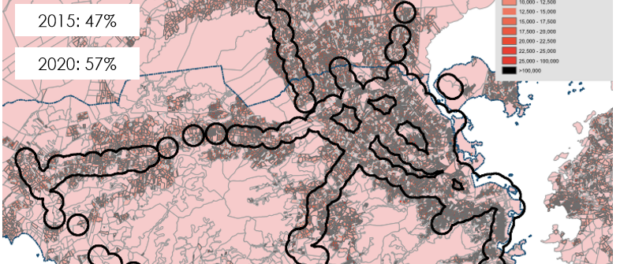

But according to Linke, commute times provide better indicators of quality of life: 26% of those living in Rio city itself and a statewide average of 20% of people spend more than one hour commuting between home and work. Linke argued that managing transport should be a priority for megacities like Rio de Janeiro. In all megacities, the population is likely to have doubled by 2030 in relation to 2000 levels, occupying three times more physical space than they did at the beginning of the millennium, and accounting for 75% of economic production worldwide.

“More than half of those living in Japeri spend over an hour traveling outside of their district to work every day,” said Linke. “This is primarily a mobility issue, but it’s caused by urban planning problems. We have to try to pressure the [mayoral] candidates to address this issue.”

Linke’s research advocated three main strategies: the creation of job opportunities away from the main city and in the surrounding regions of the metropolis, the improvement of sustainable public transport and its infrastructure, including pedestrian and bicycle options within cities, and the “de-incentivizing” of private transport and cars.

“It is crucial that we understand what the inequalities in mobility reflect,” said Linke. “We have a serious problem, with public transport that is ultimately a necessity and on the other hand an increase in the number of vehicles in the city and an investment in automobile infrastructure that benefits very few.”

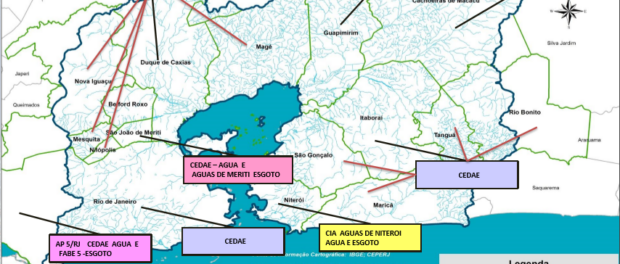

Engineer Eloisa Elena Torres spoke about sanitation and pollution challenges facing the city, with the notoriously polluted Guanabara Bay remaining one of Rio’s biggest environmental challenges. Torres’ maps showed how waste from the city, Baixada and Eastern districts all flow directly into the bay.

“There’s no problem with what’s actually in human waste,” she said. “The problem is that the city is complex, and the substances we produce are also complex, and we don’t know how this will impact the environment.”

Torres’ research placed potential socio-environmental impacts of pollution of the bay into six categories: unsanitary conditions; quality of life and health risks; watershed threats; real estate and environmental degradation and depreciation; implications for fishing and water activities; job and income losses with a decline in tourism; and risks to marine life.

Basic sanitation was another factor affecting quality of life that varied greatly between districts: 99% of Nilópolis residents in the Baixada Fluminense had access to sewage systems, but the same could be said of only 12% of those living in Maricá in the Metropolitan East. For the 22.2% of those living in non-upgraded favelas in Rio–nearly 10% higher than the state average–sanitation remains a primary point of contention.

Torres’ main concern is the looming privatization of sanitation, owing to virtual monopoly of state-owned water firm CEDAE, its public-private partnerships and potential government plans to sell off the company–placing control of sanitation far out of the financial and political control of Rio citizens.

Public security researcher Silvia Ramos addressed concerns over growing urban violence in Rio state. Mihessen’s research showed how this, too, varied across different districts: for every 100,000 inhabitants in Queimados, for example, there were 72.4 homicides on average, a figure markedly different from Rio municipality, which had 18.6, and from the state average of 25.4.

“I think we have to pay a lot more attention to territorial inequalities,” said Ramos. “Territorial inequalities are much deeper than we already know: it may be the most important way for us to understand everything today, including violence, as well as any inequality between gender, age, class, income, race.”

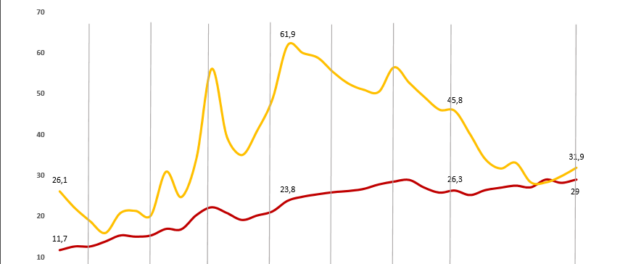

Ramos’ research shows how violent crime rates in Rio de Janeiro have steadily decreased over the years. The introduction of Pacifying Police Units (UPPs) initially had a significant impact in reducing violent crime in the city’s favelas, although in recent years this has crept slowly back up, perplexing policy makers.

“There are various explanations for this, but it is a police project,” she said. “There were 9,000 police introduced, all new and all young, and this produced a wave [where violent crime moved from the municipality of Rio to the Baixada Fluminense]–not just in the favelas but all across the city.”

Ramos also touched on the under-reported issues concerning violence and crime in the state: that overall crime, including violent crime, was much higher in the Baixada than in the city, and that if violent crime is higher, other types of crime often reflect this. But for Ramos, the most worrying element of all is the media’s capacity to swiftly forget violence.

“Everyone saw the map of violence [when it was published in 2012], and a week or two later didn’t talk about it. Newspapers increasingly follow a model of silence when it comes to talking about violence. We are talking less and less about it.”

The mayoral elections will take place in October 2016, after the Olympics. In addition to the recently-declared state of calamity, existing budget deficits, failures to address problems with education, healthcare, sanitation, transport, and crime, Casa Fluminense’s research presents an opportunity for candidates to address matters that will likely have a greater immediate impact on residents’ lives than the Games. Tonight, July 26, is the official launch of Casa Fluminense’s Agenda 2017 proposal, signed by over 50 civil society organizations and think tanks across Greater Rio. Mayoral candidates from across the region have been invited.