Cycling activist Carlos Leandro de Oliveira, 35, says his interest in cycling began during a moment of financial struggle. “I had gone three days without receiving my salary,” he says. “I didn’t have money to pay the bus fare to go to work, so I began cycling from Queimados to Rio. That’s when I saw I didn’t need to depend on public transport.” Leandro has since dedicated himself to promoting cycling as a cheaper and more sustainable method of transportation for his community in Queimados and Japeri, municipalities located in the Baixada Fluminense region of Greater Rio.

Leandro was born and raised in Queimados and studied environmental management at the Carlos Branco University. His current environmental consultancy aims to “stimulate, through the engagement of government, civil society, places of learning and private initiatives, the adoption of bicycles as methods of transport so we can have a more humane and less motorized city.” Under his activist pseudonym Carlos GreenBike, Leandro plans to cycle the Rio Doce area in Minas Gerais in November in recognition of the tragic gigantic toxic mudslide that occurred at the Samarco mining site in Mariana last year. “The goal is to see what really happened, and to see how residents are doing one year later,” he says, noting that it is easy for the public to forget about such incidents once the first wave of press has passed.

Leandro recently participated in the Casa Fluminense bicycle tour of metropolitan Rio, as part of their #Rio2017 campaign. The campaign aims to draw attention to Rio’s development goals post-Olympics, and to promote a more unified concept of Rio as inclusive of its greater metropolitan area, which is home to 74% of the state population. According to Casa Fluminense, more than half the residents of Japeri spend more than an hour commuting to work each day, contributing to a life expectancy for Japeri residents that is two years shorter than for residents of Rio city. As Leandro points out:

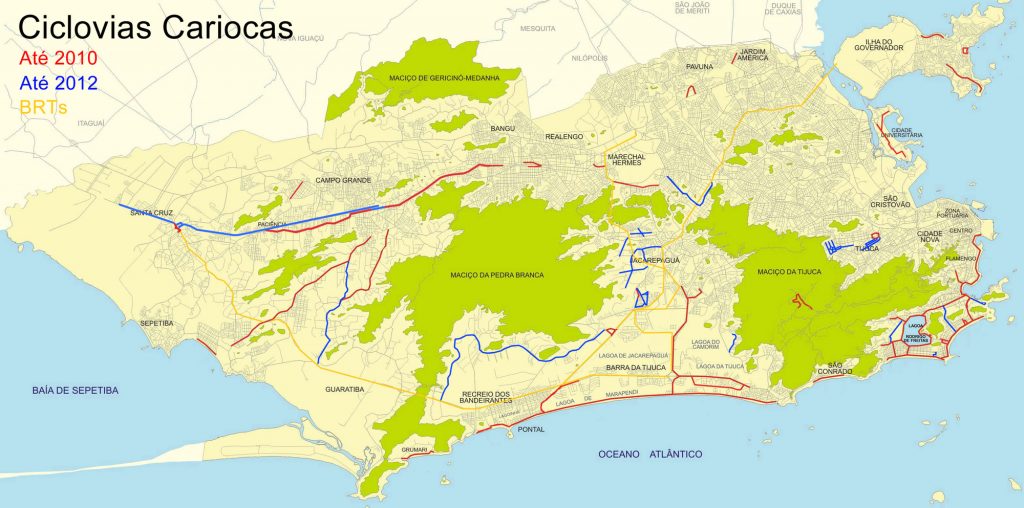

“The Rio de Janeiro city government always claims that Rio has the largest bike path system of Latin America. But bike paths for whom? Because the majority of the bike paths in Rio are in the South Zone. If you are coming from the Baixada Fluminense and you disembark at the Central Station, you have no way to make the connection between the station and the South Zone bike path system without passing through streets which are dangerous for cyclists.”

Leandro describes a number of hurdles to commuting by bike posed to those who live outside Rio’s city center. Bikes are only allowed on Rio’s metro and train systems after 9pm on weekdays and on weekends. “There’s no structure on the train where you can leave your bike,” he says, “and people look at you like you’re an extraterrestrial.”

Leandro also highlights the lack of places to lock bikes: “In Queimados, many people ride their bikes to the station, but there’s nowhere to lock your bike, and bike robbery rates are very high. You can’t take your bike to go shopping and leave it outside the store with peace of mind, you have to constantly keep an eye on it.”

Mayor Eduardo Paes promised to build 450 kilometers of new bike paths before the Rio 2016 Games to deliver on the City’s promise that the Olympics would bring urban renewal, sustainable development and inclusivity. Neighborhoods in the Baixada might have benefitted especially, as Leandro says there are no bike paths on the margins of Rio. Yet according to geographer Hugo Costa, paths that were constructed have been built almost exclusively in South and West Zone neighborhoods which already have the most leisure space and lowest population density, respectively. Residents found the 22km of bike paths promised to the Maré favela complex in the North Zone left incomplete and shoddily constructed.

In addition, a special policy adopted specifically for the Olympics rendered commuting by bike nearly impossible to Rio’s residents during the Games. “During the Olympics and Paralympics–which supposedly promote sports, accessibility and inclusivity–no one could enter the metro or train with a bicycle,” Leandro describes. “It was a form of exclusion.”

Yet Leandro remains hopeful that while the Rio 2016 Olympics did not succeed as a “landing point” for legacies, they can be used as a “jumping off point” for new improvements.

Donations to Carlos Greenbike’s ecocycle trip along Rio Doce can be made at on his Kickante crowdfunding campaign until October 22, or by contacting him at +55 21 97511 3860 or through the Carlos GreenBike Facebook page.