This is the first in a five-part series titled Housing Policy Lessons from Rio’s Favelas. We hope this series will inform debates on housing and favela upgrading and that Rio’s new mayor, Marcelo Crivella, will design policies that address the challenges favelas face while recognizing and strengthening their attributes, by actively engaging with residents in policy design and implementation.

Lesson 1: Construction in the favela is different to the formal city

Building a home in a favela comes with a separate set of challenges to those in the formal city. One difference with construction in the favela is that it is done iteratively, taking many years and involving residents’ management of the entire process.

“The favelas were built by the people and not by the public policies. The public policies when they arrived, like today, only arrived halfway. It was the residents that built the favela. This is the idea of the collective and the permanence of the place.” – City of God, West Zone

Homes in favelas grow and expand along with the needs of the family. Contrary to popular belief that they are shoddily built, over generations homes are usually built with brick, fortified concrete and steel, since most of a family’s paycheck over generations has directed to such improvements. Common materials include concrete, bricks, steel bars, sand and rock. The building process is normally controlled by internal rules (though in cases where POUSOs have been established the government does regulate building) and benefits from the expertise of builders that live and work in the communities.

“Here in Laboriaux we have a lot of local contractors. My neighbor is one, he lives two houses up the road. My uncle is one. There was one I met on the street actually who was working on another construction project. That’s how it works; you go and look and observe the services of the guy and decide if it is worth talking to him. You also have to think about the payment.” – Rocinha, South Zone

The first step in construction is finding a place to build and decide how to build. For many older favelas, residents must build on top of previous housing or creatively expand their homes because of lack of space. In more distant communities, the constraints are money and time.

“The hardest part is managing the project. You have the material, resources, buying, storing, cleaning, contracting guys to build, and explaining it all. Organizing the entire project is very difficult.” – Rocinha

First, there is the problem of financing the project. In many instances, families save and spend slowly over decades to make their home the way they want it. Traditional methods of financing through banks are not accessible, which is a large hurdle for construction because residents must rely on informal installment payments or pay in cash.

“You have the issue of when you buy a home today in a favela, more in the South Zone, but maybe the North Zone, that you have to pay all the money in cash. I think the negotiation is maybe the easiest part because people understand more. I think the relationship is much more personal when you buy a house in a favela.” – Cabritos, South Zone

Residents in favelas also face the problem of construction itself. For denser hillside communities, difficulties include finding ways to get material up steep hills to the building sites and finding storage. The logistics of construction can also be complex, requiring management of time, possibly multiple workers, material, a budget and this all going on while still trying to live in a place.

“Logistics and the space are the hardest parts. Carrying the material, having a place to put the material and space to build are hard because lately there has been only space above. The easiest part of building a house in a favela is the foundation and roof because people come together to make it.” – Complexo do Alemão, North Zone

Homes are not the only part of the community that residents build themselves; there are many community-built public infrastructure projects within favelas. There are even some instances, like in Asa Branca, where the self-made infrastructure–in this case sewerage–was high enough quality to integrate into the formal system.

The self-made nature of favela construction is born of necessity and is often precarious early on, but ultimately can transform into an asset of the community. Policies should take into account the design of existing infrastructure and recognize that the original design of these infrastructure systems was a response to local needs and circumstances. Adjustments to this must therefore involve deliberate and meaningful community consultation. A collective identity is a positive attribute of favelas and policies should work to build on and strengthen this identity.

Rather than impose traditional construction methods used in the formal city, policies should adapt to the informal nature of Rio’s favelas and help to assure the construction of homes within them is just, structurally sound, sanitary and preserves the environment.

Lesson 2: Residents benefit from the collective nature of their communities and governments can leverage this to promote dignity

There are over 1,000 favelas in Rio, and each of these communities has a unique history. It is critical these stories be respected when developing policies because there is often a stronger sense of identity in favelas than in the formal city.

It is dangerous to design policies that view favelas, which are rich with history, as “less than.” The stigma associated with these perceptions can cause policies to be made in ways that penalize and criticize favelas for their “problems” without focusing on their assets, and thus dismantling such assets in the process of finding solutions.

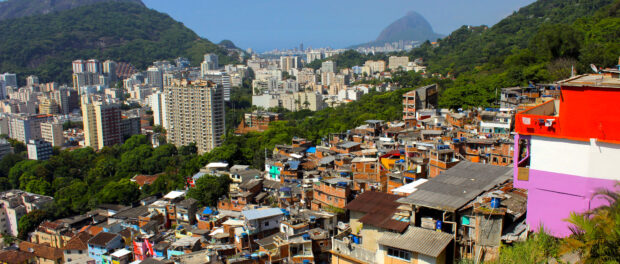

“With time, I started to see that it is a beautiful place. When I started to really look, I started to admire the beauty: the colors, the opposition between the favela and the formal city and this type of nature. From my house you can see Pedra da Gávea and that in contrast with the favela is beautiful. At night the favela seems like a giant Christmas tree because of all the various lights turned on.” – Rocinha, South Zone

There are many people who wish to stay in their communities, even if the choice was not theirs to move there in the first place. Living in a place where one feels comfortable and proud is important not only for the well-being of a person, but also for the broader ecosystem the person lives in. Housing policy design should bolster this.

“I didn’t choose Asa Branca, it chose me; it’s different. I arrived here and there were three huts in the mud. I help the transformation of this area because I like it. I raised my seven children here. Asa Branca saved my life. Here you feel like it is the best place in the world. We have everything we need here to live well.” – Asa Branca, West Zone

Communities’ physical infrastructure has a history in and of itself and is the result of decades of community investment. Incorporating real participatory measures into the formulation of upgrading policy will guarantee productive and effective outcomes for residents while increasing community engagement, pride, a sense of belonging and citizenship.

Rio’s favelas naturally have qualities urban planners around the world today seek to emulate. Many are close to middle or upper class areas, meaning Rio already benefits from mixed-income neighborhoods that many cities are working hard to foster. Every region of Rio benefits from socio-economic diversity, meaning the economic ecosystem benefits from nearby access to a wide array of skills, professions and cultural qualities and workers, at least in South Zone favelas, from shorter commutes than would be the case were the poor relegated to the urban periphery.

“The poor don’t want ease because we don’t have ease. It is more difficult for us anyways! The poor don’t have ease with anything. If you want high quality transport, you have to fight for it. If you want water on your street and it isn’t working, you have to buy the pipe and put it in.’” – City of God, West Zone

Perhaps the most prominent asset of favelas is their affordability. Since more than 23% of Rio’s population lives in favelas, they are Rio’s de facto affordable housing stock. Policies should maximize the assets that exist in these communities like walkability, low rise high density development, mixed use, affordability and their proximity to work.

Full Series: Housing Policy Lessons from Rio’s Favelas

Part 1: Construction and Community

Part 2: Collective Action and Diverse Needs

Part 3: Distrust, Gentrification and Titling

Part 4: Public Housing

Part 5: Proposing Solutions