This is the fifth article in a six-part series that comprises the book chapter entitled “Not Everyone Has a Price: How the Small Favela of Vila Autódromo’s Fight Opened a Path to Olympic Resistance” recounting the story of Vila Autódromo’s struggle. Written by Theresa Williamson, executive director of Catalytic Communities,* the chapter is part of the book ‘Rio 2016: Olympic Myths, Hard Realities‘ edited by economist Andrew Zimbalist. To read our review of ‘Rio 2016,’ click here. RioOnWatch would like to thank Brookings Press for providing the permission to republish the chapter here in its entirety.

In May 2014 at a second OsteRio event, just as the university planners and community residents issued a map showing that hundreds of residents remained committed to staying, Mayor Paes told the audience that it was “difficult to prepare an upgrading plan when there [were] so many people coming to [them] looking to leave” but that they would “see what remains of the community [after compensations were all provided to those leaving], and that of what remain[ed] . . . so long as they [were] not in access areas [for the Olympic Park], [they would] upgrade as promised.”

One year later, even with Rio de Janeiro’s first-ever market-rate compensations to favela residents, even under so much physical and emotional stress, by May 2015 the mayor had reached that limit and was unable to convince 170 of the remaining families to leave. Rather than upgrading what was left of the community to permit the smaller portion of remaining residents to remain, however, Paes had shifted to an entirely new approach.

On March 20, 2015, fifty-eight homes had been marked for removal via an eminent domain decree, with future decrees offering the possibility of more homes suffering a similar fate.1 It was by way of this decree that all of the community’s earlier leaders were eventually evicted, and as a result of the eminent domain decree stipulating that the courts determine the value of the land in question, their compensations were a fraction of those provided to residents who had taken prior compensations. Thus, those most committed to the community, who fought so hard on its behalf and wanted so deeply to remain, were ultimately those who received the worst compensations, a form of searing revenge by the mayor. Guimarães, Nascimento, and Brito were all removed in August, in one excruciating eviction after another, as were numerous other organizers who had come to represent the cause.

Perhaps the single most critical turning point in the community’s struggle came during this period. Building a home, particularly in a favela, can take decades. Tearing it down takes a matter of seconds. Municipal workers targeted homes covered by the eminent domain decree in those weeks, assigning houses for attention by hungry bulldozers following compensations being deposited in the bank accounts of their owners. And so there was a gaping threat that homes that had not yet been compensated for would be torn down. To protect themselves from ending up homeless, residents formed groups to watch over demolitions.

On June 3, 2015, such a scenario unfolded. Two homes that had not yet been compensated for were targeted for demolition. Residents formed a ring around the houses as they attempted to explain that the demolition could not go forward. Public defenders and supporters were regularly in the community during those weeks and months and joined them. Yet on this fateful day the municipal guard reacted violently, using rubber bullets, pepper spray, and batons on the protesters and injuring several residents. Some required surgery. The images of the municipal guard’s barbarity circulated on Brazil’s TV networks, in newspapers, and around the world.

This day was a game changer for the resistance movement remaining in the community. One of those most injured was Maria da Penha Macena, a small, agile woman in her fifties and one of the friendliest people one will ever meet, beaming with positivity and optimism steeped in her Catholic faith. Penha had by now assumed a leadership position in the community’s struggle and was widely known by media outlets covering the resistance.

Penha was nearly the only hopeful person left in Vila Autódromo by the time of this incident. Morale had been at an all-time low. But the violent clash propelled remaining residents to recommit to the struggle. Over the ensuing months, and through to today, the community and its supporters have led campaigns, including cultural occupations, festivals, and the launch of the Evictions Museum, expanding on Vila Autódromo’s sense of community to include the now tens of thousands who were following and supporting them in their struggle.

By the time the most symbolic community structure was demolished—the residents’ association—on February 24, 2016, Vila Autódromo was no longer felt by its remaining residents or their supporters to be simply the original blueprint of their community. The concept of Vila Autódromo had expanded to represent a broad, even global, social struggle reflected in one of the community’s many slogans, which was stamped on its walls: “Not Everyone Has a Price.” Penha coined the slogan, summarizing the movement for visitors and the press. And it was exactly that notion that captivated so many who grew to embrace the community as their own.

The eminent domain decree ultimately led to the eviction of almost all of the community’s remaining inhabitants. The two final houses demolished within the decree belonged to Maria da Penha and Heloisa Helena Costa Berto. Berto was a Candomblé priestess whose home had served as a spiritual center and who was chronically mistreated by city workers, even receiving death threats. Berto and Penha along with two other women, Sandra Maria de Souza and Nathalia Silva (Penha’s daughter), became Vila Autódromo’s best-known leaders in the final stages of the community’s resistance and have since received widespread recognition and awards from city and state governments, as well as international human rights organizations.

The final eminent domain evictions took place during the last week of February and the first week of March 2016, witnessed and documented by remaining residents along with support from dozens camped out overnight in the community on those final weeks. Vila Autódromo was now down to twenty families that were both outside the decree and had remained steadfast in their unwillingness to negotiate with the city throughout the entire process.

The final stage of Vila Autódromo’s pre-Olympics struggle now began. It was clear that the city would not leave the area looking like a war zone come August 5 and the Olympic Games’ opening ceremony. And, of course, at least a couple of months would be needed to prepare the site. So whatever was to happen to Vila Autódromo’s twenty remaining families would have to be decided by early June. This was just two months away.

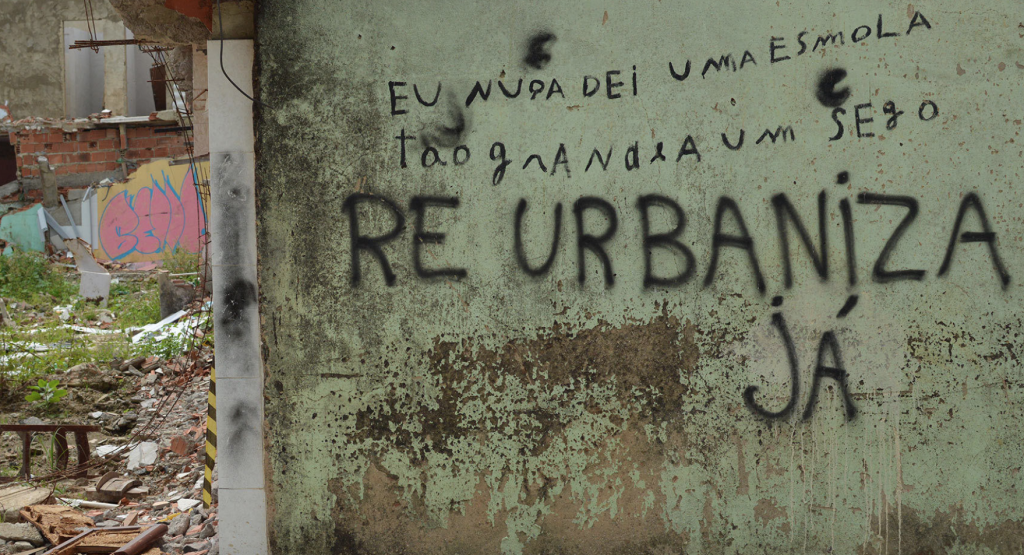

Once again taking control of the broader narrative and keeping spirits high during those few remaining demolitions, on February 27, 2015, Vila Autódromo residents and supporters launched the #UrbanizaJá (#UpgradesNow) social media campaign, calling on supporters to post videos on social media using the hashtag and declaring why they wanted Vila Autódromo to be fully upgraded now. On the same day, they launched an updated version of the Popular Plan, considering the reduced nature of the community.

Mayor Paes had declared publicly over the years, on numerous occasions, that he would not remove anyone who didn’t agree to relocation. His administration had sent in municipal workers to do the dirty work of “convincing” residents through a variety of means and then made use of a questionable eminent domain decree. But now no such option was left. The final twenty families had never even entertained the idea of negotiating, and nothing short of a violent eviction would remove them.

The #UrbanizaJá campaign quickly produced dozens if not hundreds of videos on social media, including high-visibility posts from Brazilian celebrities Camila Pitanga, Gregório Duvivier, and Bruno Gagliasso, as well as internationally known figures like David Harvey.

On March 8, 2016, the same emotional day that the home of Maria da Penha was demolished and she went on to receive a major award from the Rio State Legislative Assembly, Mayor Paes held a press conference that community members were restricted from to announce his plan for the community. The mayor’s plan ignored recommendations made in the updated Popular Plan and instead proposed not the upgrading of the community but the construction of a set of new homes on a single street, maintaining only the Catholic church from the original community’s blueprint. Residents insisted on a meeting with the mayor to discuss the proposal directly, and it took place on March 15. On that day, the community and mayor reached a tentative agreement, based mainly on the city’s proposal. The final agreement would come to be the first collectively signed relocation agreement in favela history.

As a result of their extraordinary resistance efforts, and with supporters and the media watching, over the subsequent months the remaining residents held firm, watching and waiting, then actively participating, in relocating to their new homes. Several lived in temporary trailers on the site for a number of weeks, while others remained in their original homes as the new houses were prepared. Maria da Penha had the opportunity to speak of the community’s struggle to the United Nations in Geneva. Media outlets from around the world made daily visits, reporting on the community’s struggle and relative success. Technical partners from the federal universities watched over construction quality. The entire original community was paved over, parts became parking; others became access roads (the final justification used by the city for demolitions). But the bulk of the community’s land was paved over with no apparent purpose. The hundreds of trees Vila Autódromo residents had planted over decades were toppled at some point during the demolition process, leaving the area barren and synthetic, like its modern neighbor, the Olympic park.

Vila Autódromo launched the Evictions Museum on May 18, 2016, and kept up weekly cultural events and meetings in the months building up to the Games, during the Games, and afterward. The original 700-family, relatively bucolic and green favela with large-lot homes by the lagoon exists only in the memories of those who lived there or visited prior to the onset of 2014 demolitions. In its wake are twenty small, identical, white homes lining a wide street, named Vila Autódromo Street, surrounded by asphalt and pounded by the hot sun. One resident, Delmo Oliveira, caught in a legal battle with the city that excluded him from the twenty units built prior to the Games, has managed to maintain his original home.

In the end, the drawn out and painful eviction of Vila Autódromo’s residents cost the city of Rio over R$327 million, as compared to the Popular Plan’s budget, which would have upgraded the original community for under R$14 million. More than R$105 million was spent on the Parque Carioca public housing complex alone. At least another R$220 million was paid out in financial compensations. And the city’s final rebuilding of Vila Autódromo cost at least R$2.9 million. Today, the city also faces a lawsuit: 110 of the families that received compensations are suing the city over the unjust natures of those compensations in relation to those of their neighbors.

While not the victory residents fought for, and certainly not the victory those evicted under eminent domain (and even many who took compensations) longed for, the fact that those who held out succeeded in staying on their original land in the face of such tremendous pressure and power is an unequivocal success. And these community members have gone on to represent Rio’s favelas in international forums like Habitat III and the United Nations, and their archives delivered to Brazil’s National Historical Museum during a ceremony on International Museum day, May 18, 2017, one year following the founding of the Evictions Museum. The story of the community’s steadfast early Residents’ Association President, Altair Guimarães, evicted during the eminent domain period, was in April 2017 recognized in a documentary titled “One Man, One City, Three Evictions: The Human Cost of Rio’s Growth.”

Vila Autódromo’s illustrative story serves as a glowing example and inspiration to communities in Rio and around the world. The small favela forged a path that communities facing eviction in the name of the Olympic Games or any other megaevent or megainvestment project can look to for inspiration or strategic lessons and on which they can base their movements. And the residents who succeeded in remaining on the new Vila Autódromo Street have set the community up to host and support such organizers.

Click here for Part 6.

This is the fifth article in a six-part series that comprises the chapter entitled “Not Everyone Has a Price: How the Small Favela of Vila Autódromo’s Fight Opened a Path to Olympic Resistance” recounting the story of Vila Autódromo’s struggle. The chapter is part of the book ‘Rio 2016: Olympic Myths, Hard Realities.’ RioOnWatch would like to thank Brookings Press for providing the permission to republish the chapter here in its entirety.

Videos from the Violent Day of June 3, 2015:

On March 8, 2016, International Women’s Day, Dona Penha’s house was demolished—the same day that she was honored at the Rio de Janeiro State Legislative Assembly (ALERJ):

Videos from the #UrbanizaJá (#UpgradesNow) Campaign:

Additional Bibliographic References

[1] “Prefeitura remove 58 imóveis na região da Vila Autódromo,” O Dia, March 20, 2015.

Complete Series: Not Everyone Has a Price: The Story of Vila Autódromo’s Olympic Struggle

Part 1: (Re)Introducing Favelas

Part 2: Introducing Vila Autódromo

Part 3: Vila Autódromo’s Rise as a Symbol of Olympic Resistance (2010-2012) [VIDEO]

Part 4: Intimidation and the Critical Turning Point (2013-2014) [VIDEO]

Part 5: The City Proceeds with Eminent Domain and Violence (2014-2016) [VIDEO]

Part 6: Conclusion—Vila Autódromo in the Context of Rio’s Olympic Evictions

Also see: Timeline of Vila Autodromo

*RioOnWatch is a project of the NGO Catalytic Communities