Landslides and flooding as a result of heavy rains are nothing new, especially for Rio de Janeiro. But over the past years, the situation has gotten visibly worse. While increasing climate vulnerability is a global concern, coastal cities like Rio—situated along the Atlantic Ocean with a terrain that is both mountainous and low-lying—are predicted to be particularly hard hit by natural disasters.

Above is an interactive graph from Our World In Data showing globally reported landslides over the course of the past century. With some variability from year to year, the overall upward trend in landslide occurrences is clear. In tropical countries like Brazil, rapidly changing weather patterns will have an even more distinguishable effect.

Brazil’s National Meteorology Institute (INMET) maintains an online database of information regarding Brazilian weather patterns over time, such as average temperature, average rainfall, and humidity, dating back to 1910. Though a search through their historical rainfall maps shows little variation in monthly rainfall levels, Rio’s location makes it more vulnerable to flooding and landslide events due to the different characteristics of the mountainous region and its reactions to weather patterns.

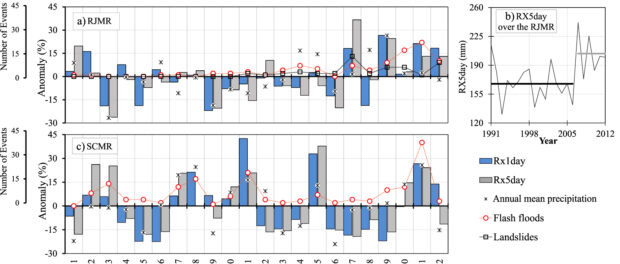

In 2016 Álvaro Ávila (et al.), in a paper on precipitation trends, flash floods, and landslides in Brazil, showed that 49 landslides and 97 flash floods were reported in the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region and 179 flash floods in the Santa Catarina region in southern Brazil from 1991-2012 alone.

In this graph, Rx1day is the annual total precipitation over one day, and Rx5day is the annual maximum consecutive 5-day precipitation recorded. The study used these, along with other characteristics such as the annual total rainfall on wet days and annual count of days when daily precipitation is greater than 30mm, to estimate the significance of the patterns of rainfall in the region.

The graph shows a Pearson correlation test, which can test whether or not some given variables have an association with a certain outcome. A P-value of 0 means no association, while anything greater than 0 indicates a positive correlation, and anything over 0.1 is considered significant. In this case, variables are a place’s weather patterns and the outcomes are flash flooding and landslide events. For Rio de Janeiro, the P-value between the precipitation indexes and landslides were 0.49 for Rx1day and 0.59 for Rx5day, and between the indices and flash flooding, 0.50 and 0.40, respectively (positive correlations in all cases).

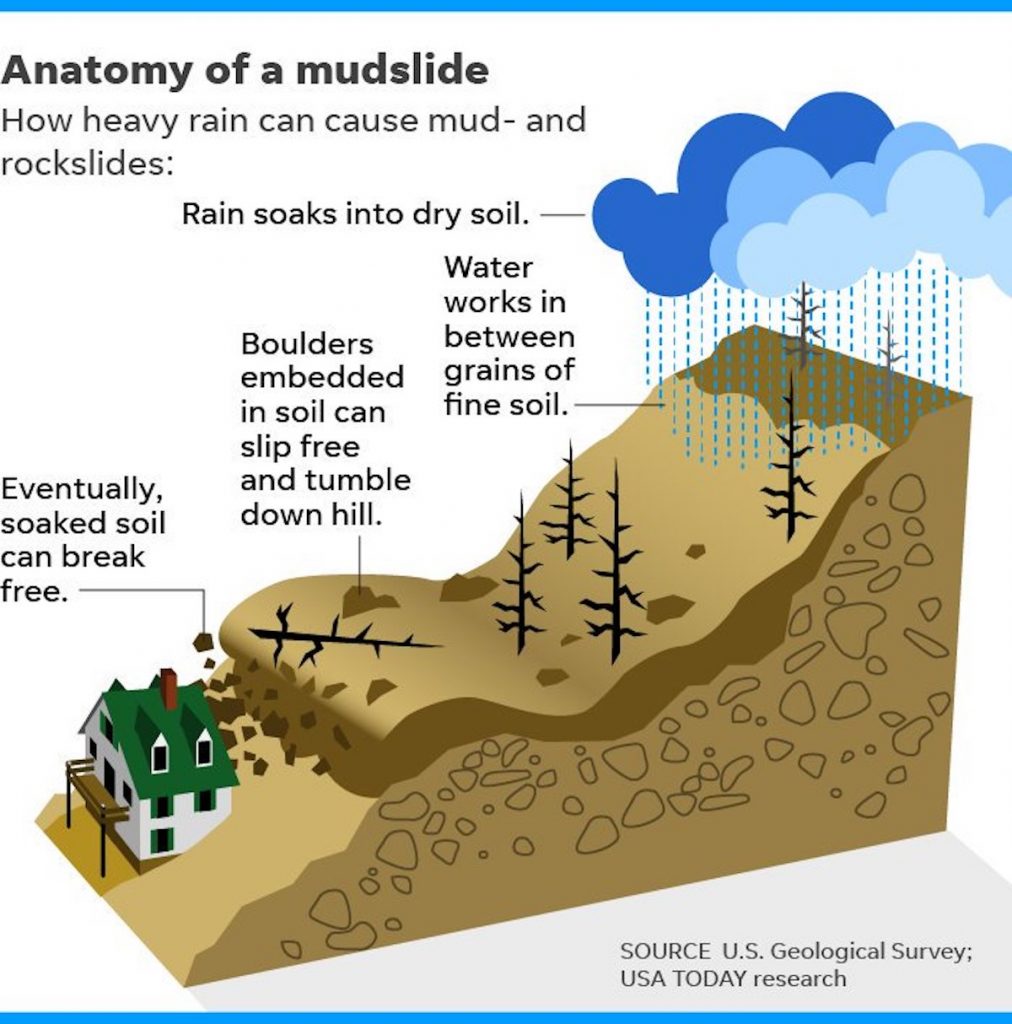

While there exist both social and technical causes of landslides, in Rio de Janeiro, these events naturally occur due to soil degradation caused by intense rains over a short period of time, and can even occur days following precipitation. As a result of a combination of increasing global climate change, a history of deforestation and urbanization, and a general lack of political will to proactively tackle environmental challenges, the city of Rio is experiencing a growing number of natural disasters with drastic consequences.

Landslides and flooding events most frequently occur in Rio during the rainy season, from December to April—corresponding to summer and early autumn in the Southern Hemisphere, when temperatures are considerably higher than the rest of the year.

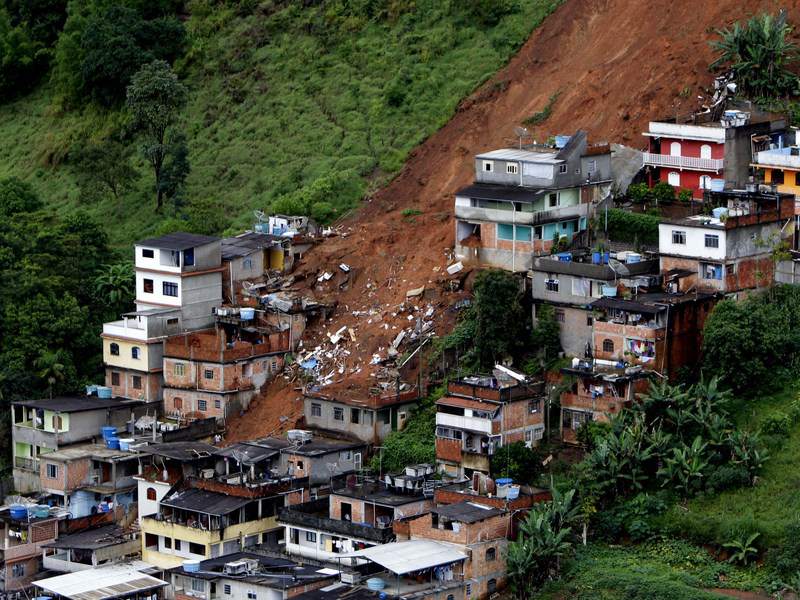

The city’s favelas—some of which are situated on hillsides susceptible to landslide risk, while others are located on low-lying land prone to flooding—are often among the areas hardest hit by these events, exacerbated by the inadequate provision of public infrastructure such as basic sanitation works and investments in retaining walls. When these disasters occur, government officials such as Mayor Marcelo Crivella and Governor Wilson Witzel tend to blame favelas, while ignoring the issue of historical and systematic government neglect.

Without proper investment in both disaster mitigation interventions and emergency response programs, many favelas will remain vulnerable to the consequences of natural disasters. Moreover, without acknowledging favelas as affordable housing solutions and instead treating even long-established favelas as problematic spaces to be eradicated, damaging stigmas against them will only serve to perpetuate harmful narratives. These, in turn, will maintain them in a precarious state, leading to even more fatalities and further physical, economic, and environmental damage.

Below is a timeline of major flooding and landslide events that have severely impacted favelas in Greater Rio over the last decade.

April 2010

On April 5, 2010, several Rio weather stations recorded a record 288mm of rain within 24 hours, well over the average rainfall amount for the month of April (140mm). The amount of precipitation within this timeframe was the highest recorded in the previous 30 years. Globo television network put this amount of rainfall into context by likening it to the amount of water needed to fill 300,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

The torrential rains of 2010 prompted the City Council and Civil Defense to add technological improvements to the city’s landslide warning and risk mitigation systems in the wake of the havoc wreaked upon communities across Greater Rio.

Fifty-two people were killed in the city of Rio de Janeiro (30 in Morro dos Prazeres and three in Rocinha, specifically the uppermost section, Laboriaux, in the South Zone; and five in Morro dos Macacos, in the North Zone), while the total death count in Rio state was well over 200—including severe devastation in Niterói, where 99 people were killed (48 in the community of Morro do Bumba alone). The death toll was higher than the 2008 Santa Catarina flooding, which caused the death of 130 people.

Approximately 160 others were injured and 15,000 were forced to leave their homes across the state. By the time the rain stopped several days later, 12,000 were left homeless. With multiple distinct landslides hitting the area, the city’s famous Christ the Redeemer statue was shut off to traffic for the first time in its history.

January 2011

Rains coming from the região serrana (mountainous region) north of Rio proper caused death and destruction in five nearby cities: Teresópolis, Petrópolis, Nova Friburgo, Sumidouro, and São José do Vale do Rio Preto. With over 26cm of water pouring down in less than 24 hours, the rain triggered a series of mudslides throughout the mountainous region. Nova Friburgo and Teresópolis each counted over 250 dead with the final death toll at over 1,000 including 13 from São Paulo. In Teresópolis alone, 1,000 people were left without homes.

During the flooding, most of the Rio area went without electricity or phone service, and 60% of Teresópolis and 35% of Nova Friburgo’s citizens still had no access to clean water days after the storm had passed.

The January 2011 storm caused one of the area’s largest natural disasters in the past fifty years and brought increased attention to rapid urbanization, infrastructure, and housing rights issues within the context of natural disasters in Rio. It also laid bare Rio’s overall natural disaster preparedness: though army helicopters were deployed to rescue those injured and caught in debris, crumbling roads and bridges made groundwork difficult for both survivors and volunteers working in the damaged area.

The disaster resulted in a governmental policy requiring updated landslide and flood-risk maps (untouched since 1994), the development of a Pilot Urban Growth Monitoring System guiding cities to include disaster risk management in their urban expansion policies, and an improved early warning system for landslides and flooding, directly linked to Rio’s Civil Defense.

March 2013

On March 18, 2013, in Petrópolis, a mountain region 40 miles north of Rio, a river overflowed its banks and flooded the center of the city. Twenty-seven people were killed, including one child and two emergency workers. Some areas of the city saw as much as 39cm of rain in 24 hours, where the normal monthly average is usually 27cm. This came just two years after the state of Rio’s most devastating natural disaster. The number of displaced people was tallied at around 1,500.

As a statewide revamping of the natural disaster mitigation strategy was conducted only two years prior, Brazil’s then-president Dilma Rousseff stated that the “prevention system warns the people. What I think is that a little more drastic measures will have to be taken so people don’t stay where they are not supposed to be [in areas identified as high risk].”

December 2013

Heavy rains beginning on December 11, 2013 caused the death of at least four people and left an estimated 6,000 without their homes. This included 400 families in the Complexo do Alemão favela alone. Many buildings also collapsed as a result of the flooding, as captured in this video. In the absence of an effective government response, many people within Complexo do Alemão and other favelas formed networks to aid those who had lost their belongings in the event and help distribute donations. On- and off-line networks developed, notably Juntos Pelo Complexo do Alemão and Occupy Alemão.

February 2018

Heavy rains starting on February 14 and continuing overnight required the city to declare a state of emergency. Galeão Airport was forced to halt operations, and the Piedade, Méier and Madureira weather stations recorded an average of 33.96mm of rain between the emergency declaration at 1:25am and 1:45am. In Barra da Tijuca, 123mm of rain was recorded in one hour.

Warning sirens were activated in 77 favelas and many roads (as well as Line 4 of Rio’s metro system) were closed due to falling trees and other debris. It was estimated that four people were killed and 2,000 were left homeless, most in the Complexo do Alemão favelas. Mayor Crivella said he was “responding to the situation” from afar while on a trip to Europe and again, those affected received urgent help from other favela residents and charitable organizations, such as community-based newspaper Voz das Comunidades and mobilization NGO Meu Rio, while the City and state governments did little.

This event was also one of the last issues raised by city councilor and human rights advocate Marielle Franco in her final speech to Rio’s City Council prior to her assassination one month later, demanding greater attention for the increase in flooding and landslide events and their impact on the city.

February 2019

Almost exactly a year later, several flash floods and landslides were recorded from February 6-8. In one hour, the city received the equivalent of one month’s rainfall. Among the hardest-hit areas were Vidigal and Rocinha favelas, respectively recording 161.2 and 164mm of rain in just six hours. Winds blew up to 100km per hour, causing several trees to fall. Six people, including one child, were killed—one in Vidigal, one in Rocinha, two in Barra de Guaratiba, and two on Niemeyer Avenue. Social media posts revealed the severe damage caused by the storm, such as this video shared by Rocinha community journalist Michel Silva.

Despite the repeated landslides and flooding events and subsequent calls for more government action, the Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry (CPI) on Flooding launched by Rio’s City Council has revealed that municipal agencies responsible for flood control and prevention measures had experienced severe budget cuts in recent years: as of April, the City has not spent a single cent on containment or urban drainage works in 2019. Likewise, the CPI found that Rio’s Civil Defense is experiencing a decreasing budget and its training programs for disaster relief for favela community leaders have suffered from discontinuity.

April 2019

The city was hit again by flash flooding and landslides beginning on April 8 and continuing overnight. Some parts of the city saw more than 310mm of rain in a single day, breaking the record for the strongest recorded rainfall in Rio in over three decades (previously set by the rains of 2010). Flash floods and landslides killed ten people and left dozens more homeless. The damage was considerably harder to mitigate, especially in favelas, given that the torrential rains hit less than a month after February’s tragedies—from which many communities were still struggling to recover.

While Vidigal received visits from the Civil Defense, overall, government response was again lacking and much of the aid and cleanup was done by favela residents themselves as a result of community mobilization efforts.

Global climate patterns indicate that the city of Rio de Janeiro will continue to experience extreme weather events—and if the current trend of inaction continues, the repercussions will continue to worsen. Favelas deserve less blame and more attention from competent public authorities. Though emergency response efforts organized by residents and community-based organizations should be applauded as they embody the spirit of resilience that is characteristic of Rio’s favelas, the government should not be absolved of its responsibility to mitigate the risk of foreseeable and preventable disasters. While landslides and flash flooding are environmental problems, they are exacerbated by the political and social stigma around favelas—which, in turn, leads to entire communities being ignored during times of crisis.

History shows that the negative impacts of these natural disasters and the government’s prevention efforts are negatively correlated: the former is rising as the latter diminishes. In the face of global climate change, more government action must be taken to prevent and mitigate these disasters. In the absence of a coordinated policy initiative to address this need, the entire city of Rio may risk irreversible environmental catastrophe.