This is our latest article on Covid-19 and its impacts on the favelas. For the original article in Portuguese written by Adriano Mendes and Bruno Henrique published by Data_labe, click here.

While Berlin and Paris resume State control of basic sanitation services, Brazil privatizes public utilities and facilitates the entrance of private companies with little interest in peripheral areas.

Is having clean drinking water from your faucet a right, or is it a product for those who can pay? Important decisions relating to the privatization of public utilities that provide essential services, like sewage treatment and water distribution, are being made amidst one of the worst health crises that Brazil has ever faced. Favelas and other marginalized territories, which suffer with a lack of basic sanitation, have watched their rights sold off as the lives of their residents are at risk. In these spaces, the numbers impacted by the tragedy continue to grow, surpassing 106,000 deaths as a result of the spread of the coronavirus. In the city of Rio de Janeiro, according to the Voz das Comunidades dashboard, which uses data from the city government, at the beginning of August, there were 4,344 cases of Covid-19 and 637 deaths confirmed in the favelas. The frontrunners of this sad case ranking were the favelas of Complexo do Alemão (395), Penha (429), and Complexo da Maré (452 cases, with 88 deaths). Meanwhile, according to data from Redes da Maré, through the thirteenth edition of their “Keeping an Eye on Corona!” bulletin, the situation in Maré is even worse than official statistics indicate: by the end of July, there were 1,435 confirmed or suspected cases and 118 confirmed or suspected deaths. Yes, it is in this calamitous context that the process of privatization of the State Water Supply and Sewage Company (CEDAE) has advanced in Rio de Janeiro.

The main argument of those in favor of privatization is that through it, we can finally guarantee the universal provision of these services, even in poorer areas of the city. People opposed to privatization argue that private companies go after profit—and basic sanitation in poor territories does not tend to be very profitable. An important factor (which was brought up during a joint public hearing that brought together the committees of environmental sanitation, the metropolitan region, human rights, and the legislative coalition against privatization) is that CEDAE is not a drain on the government’s coffers. Rather, it has brought liquid gains with a significant increase in transfers to the state government.

CEDAE is dying, long live CEDAE!

The justification for CEDAE’s sale is the Regime of Fiscal Recuperation (RRF) austerity policy agreed on in 2017, a time when the state of Rio de Janeiro was going through a profound crisis and needed financial help from the federal government. The model of concession is being established by the National Economic and Social Development Bank (BNDES) and envisions that CEDAE will continue pumping and treating water, but that water distribution and collection and treatment of sewage will be carried out by private companies, which will make CEDAE reduce its workforce by 80%, laying off about 4,000 people. The sale of CEDAE, in Rio, moves forward just as, in Brasília, the Revised Basic Sanitation Regulatory Framework was approved.

Renata Souza, a state congresswoman with the Socialism and Liberty Party and president of the Human Rights and Citizenship Commission of Rio de Janeiro’s state legislature, is against the privatization of CEDAE and points to the way the process could impact the lives of the poorest members of the population: “Few people know, but Brazil is in second place worldwide in remunicipalization of water and sanitation, with 78 cases, behind only France. The reason is always the same: low investments and dissatisfaction with privately-offered services. The investment banks, basically five conglomerates that have invested in the privatization of water worldwide, aren’t interested in providing high-quality service. What they seek is just profit, through the reduction in the quality of service and the increase in prices. In the case of the privatization of water and sanitation, that argument is absurd and I’ll explain why: there are regions where it wouldn’t be profitable for private initiatives to operate the distribution of water and basic sanitation, because the operation of the system doesn’t cover the operational costs. Only a public utility is able to operate these systems in a way that guarantees the right to water and sanitation for the whole population.”

Public discontent with the services provided by CEDAE in the last few years is part of a [political] project of dismantling the company to justify its privatization by the current administration. This is what reporting from Brasil de Fato shows, highlighting the testimonial of Ary Girota, a former CEDAE employee and president of the Niterói Sanitation Workers Union. An example of the consequence of the process of dismantling CEDAE happened in the first months of 2020: water stored at the Guandu station was being distributed to the population with an unpleasant taste and odor and dark coloration. At first, it was thought to be from geosmin. Later studies, however, revealed the strong presence of domestic sewage and industrial pollution.

At Andreza’s (32) house, in the Vila do Pinheiro favela in Complexo da Maré, this dismantling is clear: “the problem is the lack of water. Because starting at a certain time, no water is pumped to our tanks. We have to depend on a little pipe on our deck, and we have to find a way to cook, to bathe. Wash clothes? Forget about it, right? To wash dishes, we depend only on this one faucet, because it is not connected to the water tank. During the pandemic, we crowdfunded money to buy another pump, and that was when there was an improvement in the access to water here at home.” Asked if she had seen CEDAE working in her community, Andreza responded that she had not.

Congresswoman Renata Souza asserts that the public administration needs to be efficient in guaranteeing a CEDAE that can provide high-quality service to the population. Privatization is not the solution: “the question about the quality of CEDAE’s services isn’t a technical question, it’s a political question. We defend a CEDAE that is 100% public and that the excess resources of the utility be used in the improvement of the quality and reach of services. Privatization definitely is not a way to guarantee high-quality and accessible service, but rather the contrary!”

In fact, the challenges are immense, and the stripping down of public sanitation companies worsens the outlook even more. This is what the 2020 Inequality Map, recently released by Casa Fluminense, points out, with information about the Rio de Janeiro Metropolitan Region. While in Niterói water reaches 100% of the population, in Seropédica it reaches 68.4%, and in the city of Maricá it reaches just 41.8%. Regarding sewage treatment as a percentage of residents, Niterói reaches 97.7% and Rio de Janeiro, 63.5%, while municipalities like Paracambi, Seropédica, Itaguaí, Nilópolis, São João de Meriti, Tanguá, and Guapimirim treat 0%. That’s right, zero! According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, the populations of these municipalities without sewage treatment add up to nearly a million people.

Irenaldo Honório da Silva (51), resident of Pica-Pau, a favela in the neighborhood of Cordovil, explains that problems with the smell of the water in his house began long before the CEDAE crisis: “when the residents turn on the faucet, the water has been coming out smelling of sewage long before the CEDAE problem happened. The network’s sewage runs together with its water, and when it gets stopped up and residents use a pump, they pull out sewage as well. There are a lot of water pipes on top of each other, without any adequate placement technique. Here at my house, I always boil water before using it, since the water has been coming out very dirty for a while.”

Unlike Andreza in Complexo da Maré, Irenaldo sometimes accompanies CEDAE’s services in his territory, but he criticizes public sanitation works that were abandoned: “sometimes CEDAE comes to unblock some pipes and separate the running water from the sewage network. In 2015, the State built a treatment station at the top of the Irajá River, finishing up in 2016, but it still isn’t functioning today. The station would carry all of the sewage from Cordovil and Brás de Pina, going through treatment and ending up clean in Guanabara Bay. Now, it turned into a white elephant. They spent a lot of money for nothing.”

Universalization in 13 years, the utopia of the Revised Basic Sanitation Regulatory Framework

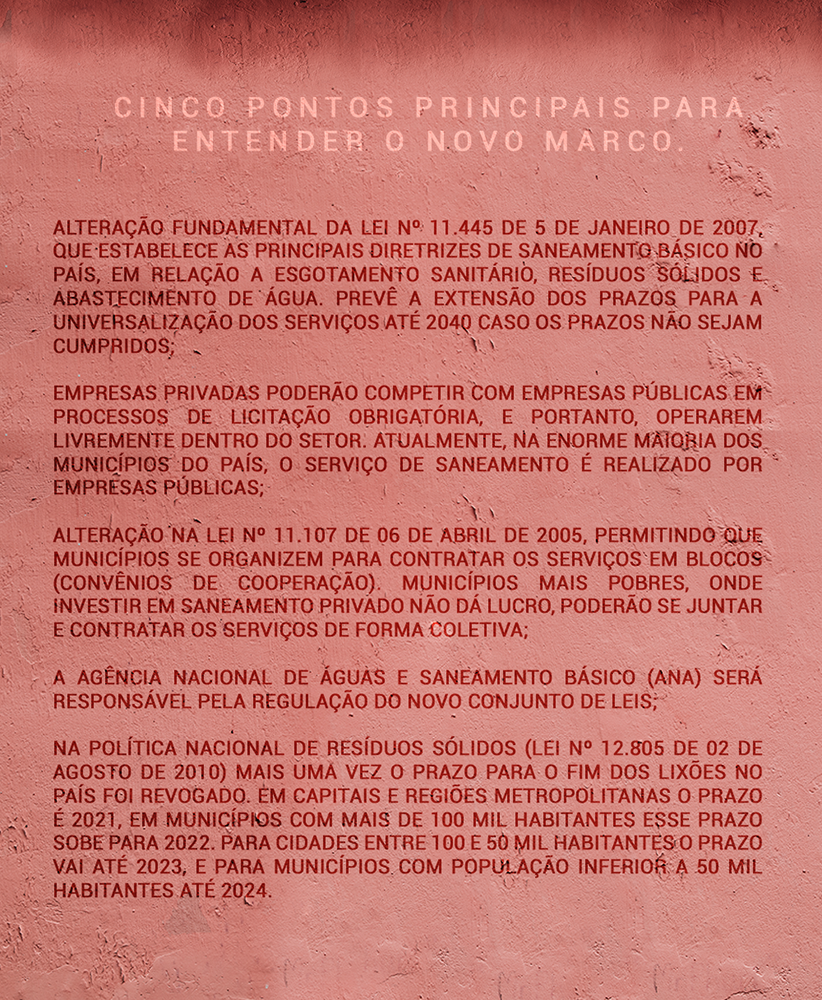

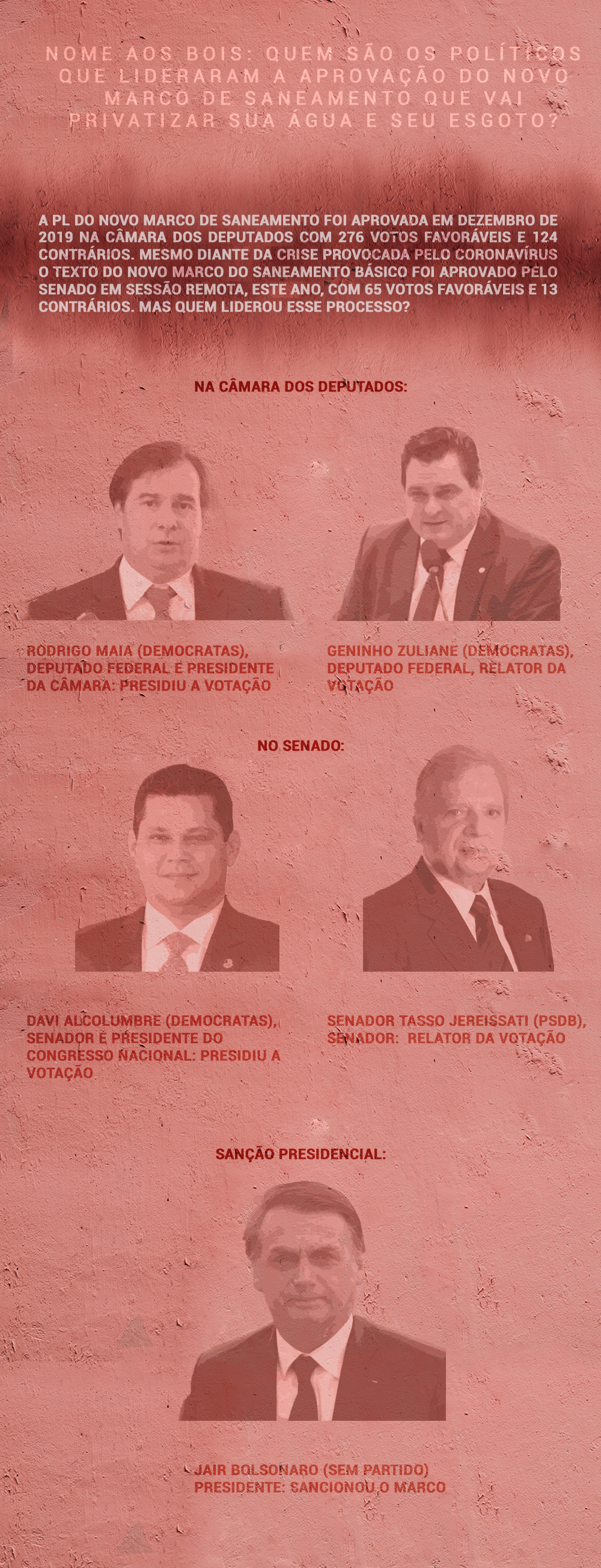

Approved on July 15 by President Jair Bolsonaro, the Revised Basic Sanitation Regulatory Framework is audacious in terms of its deadlines, this because it foresees the universalization of access to basic sanitation services in the Brazilian territory by December 31, 2033. This would mean that in just 13 years, the country would have access to water for 99% of the population and 90% for sewage, as well as an end to landfills.

According to the National System of Information About Basic Sanitation (SNIS), today, there are 100 million people without access to the sewage network and 35 million without access to treated water. Brazil’s favela population is 13.6 million residents, larger than the entire population of countries like Cuba and Portugal, who live in precarious conditions of basic sanitation even today in 2020. Is it possible to revert this entire situation in 13 years without raising prices on the services and further deepening inequalities?

The inequality across Brazil’s regions becomes brutally visible when we observe data about the locations of landfills in the country. According to information from the National Solid Waste Plan, in 2018, 37,360.8 tons of waste were thrown out in landfills per day. Of that amount, 63% was thrown out in the Northeast and 3.8% in the South. In that year, the plan indicated the presence of 2,906 landfills in Brazil, distributed among 2,810 municipalities. In the Northeast, 89% of municipalities have landfills; by contrast, in the South, just 15.3% of municipalities have them. The end of all landfills should have happened by 2014, in accordance with Article 54 of Law 12,305 of 2010. However, the law wasn’t carried out, and, now, yet again, an end to landfills was postponed by the Revised Basic Sanitation Regulatory Framework.

Professor Alexandre Pessoa, a civil sanitation engineer and researcher with Fiocruz‘s Joaquim Venâcio Polytechnic School of Health, explains how inequalities that are already present can be deepened with the privatization policies: “I view the change of the Basic Sanitation Regulatory Framework in Brazil with much concern, because without a doubt, it advances as part of a neoliberal wave that weakens public policies. The participation of the private sector, without a doubt, is based on a criterion of profitability. We are already giving up on the understanding that sanitation is a human right.” Alexandre criticizes the lack of utilization of health criteria in the decision-making processes about sanitation services: “the favelas obey the criteria of attractiveness for the private sector [for the placement of landfills], but in public health criteria it is exactly the opposite.” Born and raised in a favela in São Paulo, a famous poet wrote: “have faith, because even in the landfill flowers are born.” Profit as well, as indicated by the recent interests in privatization of sewage and trash in Brazil.