This is the first article in a series of three on Brazil’s Black Coalition for Rights.

“We are not born black, we become black. It is a hard, cruel understanding that one develops out in the world. A black person who is conscious of their blackness is in the fight against racism.” – Lélia Gonzalez

If the majority of the country is black—with almost 54% identifying as black or brown, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, making Brazil the second-largest black nation, only after Nigeria—why are black people not represented in spaces of power? Why are organizations from the Brazilian black movement not considered voices to be heard in nation-building projects? Why are only 17.8% of parliamentarians in the National Congress black or brown?

The answer lies in the structural and secular racism present in Brazilian society, which, in spite of an established democracy, does not guarantee access to rights for the majority of its population, which is black.

“We are in a country which we must dispute. And it’s not a dispute over narrative. We do not live in a democracy. Since democracy is the practice of listening to the majority—but we have a majority that has never been heard (the black population)—it is obvious that we do not live in a democracy,” says Douglas Belchior, 41. Belchior is co-founder of UNEafro Brasil, one of the 150 entities that form the Black Coalition for Rights, which penned the manifesto “As Long As There is Racism, There Will Be No Democracy.”

“If we think of democracy as a social agreement guaranteeing citizens’ rights, we still do not live in a democracy, since most of the population has never had their full rights and citizenship respected. We, in the black movement, are always aware of this, because it is obvious in our lives and in our bodies,” says Belchior. The Black Coalition for Rights demands, in its manifesto, “the eradication of racism as a genocidal practice against the black population.”

With 46 public documents that propose policies for the country from the perspective of the organized black movement—but including all Brazilians, black, white, brown, and indigenous—the Black Coalition for Rights has existed for nearly two years, representing different voices from the organized black movement such as black women; favela residents; people from urban peripheries; LGBTQIA +; Catholics; evangelicals; those who follow religions of African origin; quilombolas (descendants of enslaved Africans who remain on their ancestral lands); people from the countryside, water, and forest; and workers who are exploited, informal, and unemployed, all in coalition to form a pact against the practical consequences of structural racism in Brazil.

“The coalition is not and will never be just an organization. It is an exercise in building a path together. It only exists through our collective action. It does not have an office, a headquarters, nor is this on the horizon. What exists is the movement’s collective political action,” explains Belchior. The Black Coalition for Rights has been fighting racism and violations of the right to life, denouncing human rights violations in Brazil.

When the country reached 100,000 deaths from Covid-19, the Black Coalition for Rights filed the 56th request for impeachment against Jair Bolsonaro, on August 12, which included 11 complaints against the president. The document was signed by 150 organizations that make up the group, with support from another 600 entities, in addition to signatures from public artists, intellectuals, and activists. Three months later, Brazil was close to reaching 167,455 deaths (on November 19) from the pandemic, which presented an upward trend and indicated the beginning of a second wave of infections in the country.

“Brazil finds itself in front of a mirror that reflects all its evils. And the only hope that is possible as a counterpoint to this white, old, rich, heterosexual, cisgender face that occupies the top of the social pyramid and most spaces of power is in the transformative potential of women, men, youth and LGBTQI +, favela residents and people from the peripheries, quilombolas and ribeirinhos (river communities), imprisoned and homeless people, who are black, who make up the majority of the Brazilian people,” declares the Coalition on its online platform for principles and agenda, on November 28, 2019.

Given Brazil’s police violence, which kills a black person every 23 minutes—according to a Senate committee’s investigative report on the Murder of Youth based on data from the Map of Violence—for months, the Coalition has denounced that as long as there is racism, there will be no democracy. “There are sectors in society that have distanced themselves from this reality all their lives, and so it is not obvious to them… that this democracy is not a reality for most. And I say that even including the progressives that are concerned with reality in a more general sense,” emphasizes Belchior.

Black Genocide: 75% of Murders in Brazil

Agatha Felix, Eduardo de Jesus, Maria Eduarda, Jonathan Oliveira, Maicon de Souza, João Pedro, João Vitor, Iago Cesar, Rodrigo Cerqueira, Carlos Alberto, Carlos Magno, Everson Gonçalves, Thiago da Costa, Viviane Rocha, Cristiane Souza Leite, Rosana Lima de Souza. What do all these names have in common? All of these people were murdered in police operations in Rio de Janeiro’s favelas, and make up part of the statistics on the Brazilian black genocide.

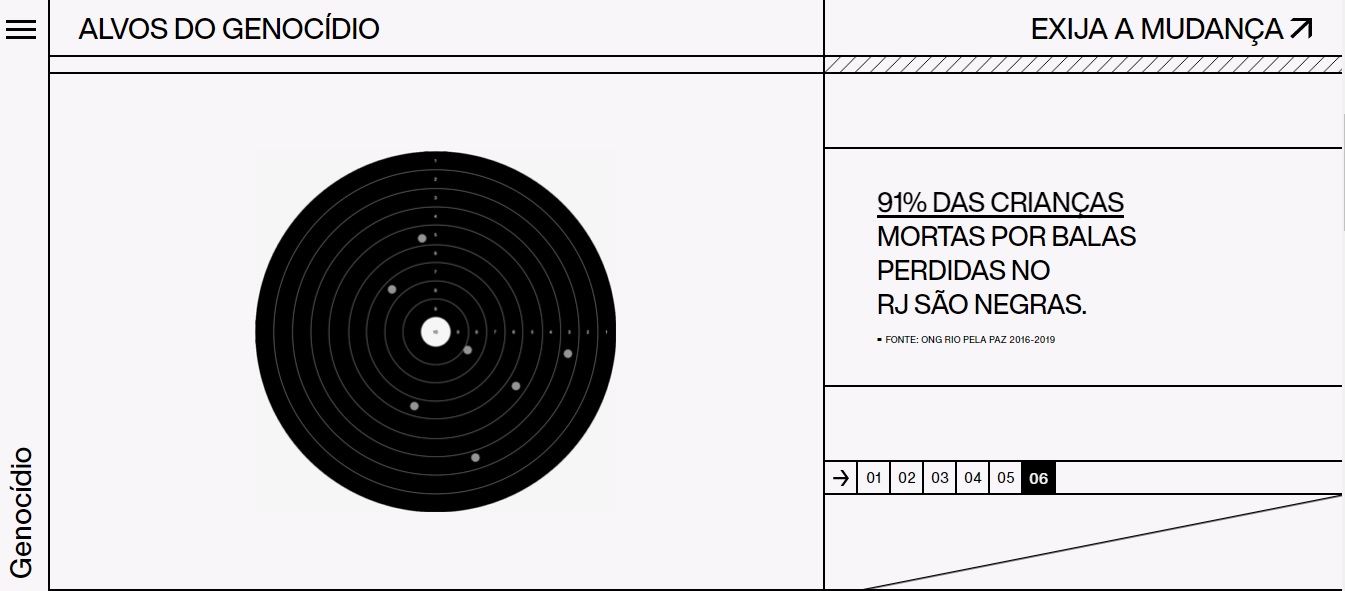

Among those murdered in Brazil, 75.5% are black, according to the Atlas of Violence. Research by Rio de Paz shows that between 2016 and 2019, 91% of children killed by “stray bullets” in Rio de Janeiro were black.

“GENOCIDE is the deliberate extermination of people, motivated by ethnic, national, racial, religious and, sometimes, socio-political differences. In Brazil, it is the result of the racism that shapes the State and society, which affects the police, corporations, political institutions, and the population as a whole,” the Coalition campaign denounced.

As part of the Brazilian black genocide, black lives are also interrupted every day in the necropolitical games that curtail access to rights, without us ever knowing their names. These realities are reinforced by the economic and social inequalities of the coronavirus pandemic. While newspapers asked people to sanitize their hands, favela residents, who are mostly black, denounced the lack of access to water and lack of ability to self-isolate in order to prevent the disease’s contagion.

“Brazil is a country with a historical and current debt to its black people. Therefore, any project toward or attempt at democracy in the country requires a firm and real commitment to fighting racism. We call on the democratic sectors of Brazilian society, the institutions and people that today say they are disgusted by the evils of racism and who claim to be anti-racist: be consistent. Practice what you preach. Join us in this manifesto, in our historic and permanent resistance initiatives, and in the proposals we defend in order to build democracy, organized in our platform,” says the manifesto As Long As There is Racism, There Will Be No Democracy.

The manifesto was launched in June 2020, in the context of increasing anti-racist struggle worldwide, after the murder of George Floyd by a white police officer kneeling on his neck. It includes signatures of prominent Brazilian artists, intellectuals, activists, and public figures, in addition to 150 other institutions within the black movement including Uneafro, Criola, Movimento Moleque, Justiça Global, Rede Contra a Violência, Voz da Baixada and the Marielle Franco Institute.

“The most conservative elite knows that democracy does not exist for everyone, and that the system oppresses black people, but they maintain this false logic of democracy as a strategic project. Our manifesto is a reclaiming of the obvious, because in Brazil, the obvious needs to be fought for. That’s why we organize ourselves so strikingly, in a coalition, to demand coherence from those who say they care about democracy, because whoever cares about democracy needs to be concerned with the racism that objectively impedes the exercise of democracy,” says Belchior, a member of the Black Coalition for Rights, which has forty-six active WhatsApp groups.

According to Google, searches for “the persistence of racism in Brazil” grew more than 5,000% from 2019 to 2020. Furthermore, “privilege” was searched at an all-time high in June 2020, followed by the search for “what is racism?”, which received the most searches of any point in the last five years. The number of searches for “Vidas Negras Importam,” “Vidas Pretas Importam,” “what is Black Lives Matter,” and “Black Lives Matter translation” was greater than ever. The data are part of a survey by Google Trends.

In light of these figures, and racism scandals across the United States, Google launched the film “Searching for Racial Justice” along with a letter pledging to combat racism within the company itself:

The Black Coalition has been working for two years to respond to the increasing erasure of rights by the current federal government. Nationwide organizing and mobilization by the black movement is not new in Brazil. At key moments in the country’s history emerged the Unified Black Movement in 1978, the Black Pro-Constitution Movement in 1988, the Zumbi dos Palmares March in 1995, and Black Women’s March in 2015, for example.

“In key moments of great crises and change, the black movement organizes nationally. The election of Bolsonaro marks one such crucial moment. We had imagined that the Bolsonaro government would be cruel to black people, and it was confirmed in the first months of his government,” explains Belchior. The first meeting of the Black Coalition took place in November 2019, at the July Ninth occupation, where more than 100 people attended, representing dozens of collectives and institutions of the organized black movement.

This is the first article in a series of three on Brazil’s Black Coalition for Rights.