The possibility of forcibly evicting the Maracajás, Rádio Sonda, and Estrada do Galeão No. 92 favelas, located near the Tom Jobim (Galeão) International Airport where tourists visiting Rio land each day, is once again haunting residents. The threat comes from the Brazilian Air Force Command (COMAER), which gained administrative control over the area, on Ilha do Governador (Governor’s Island) in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone, five years ago, effectively becoming its new owner.

Situated along Estrada do Galeão, the main expressway on the island that connects the neighborhood of Galeão to the airport itself and Praia do São Bento, these communities are home to approximately 160 low-income families, totaling over 800 residents. The land was occupied over 100 years ago, back when it belonged to the Secretary of Federal Heritage (SPU).

Although they have lived with gradual evictions and attempts at forced expropriation for over 20 years, the fear of losing everything overnight has intensified over the past two years. Since COMAER obtained the official concession to administer the area on Ilha do Governador, the threat of eviction has loomed over families.

‘That’s it, Get Out’

The land that houses these communities today was first occupied 100 years ago by migrant families from different parts of Brazil. Initially, the area was under federal administration, but in 2020 it was transferred to the control of the Air Force Command (COMAER). The three communities border the housing complex for Air Force noncommissioned officers and sergeants.

The first eviction notices were issued in the 1990s, and actual removals began in the 2000s. Despite the community’s ongoing struggle to remain, to date around 15 families from Maracajás and Rádio Sonda have been forcibly evicted from their homes.

Cristina Santos,* 62, a homemaker, has lived in Maracajás—the oldest of the three communities—for the past 35 years. Alongside her husband and daughter, she shares the fear of losing everything and recalls the last violent forced eviction she witnessed less than ten years ago.

“It’s been seven or eight years since they started sending letters saying we’d have to leave. But some [families] have been here for 100 years. My own family is already in its fifth generation [living here]. One day they just showed up out of nowhere, went to the neighbors next door and threw their furniture out the window—no mercy, no warning, no time. It was basically: ‘That’s it. Get out!’ They started saying this land belonged to them. When my mother-in-law came here, she was still a kid—her father worked on the construction of the [old] bridge on Ilha do Governador. These plots of land were given to workers on those projects. The place where the Air Force administration is today used to be a chicken farm. There was nothing here! When my father was around, there wasn’t even an Air Force yet! They don’t need this land. The day they came to kick people out, they blocked off the street, came in with trucks, the Military Police and the Municipal Guard, pushing residents around, even the elderly. They beat people up… They said they were going to store everyone’s belongings in a warehouse, but to this day no one knows where anything ended up. Many went to live with relatives. Some died because of it, from heartbreak. It’s sad. They’re cowards. There was no need for that. There are drug users living in the abandoned houses now. They beat people up and evicted them for nothing.” — Cristina Santos

Ana Maria Goulart,* 47, a saleswoman and mother of two, has lived in Rádio Sonda, in Vila Juaniza, for 23 years. She said the struggle has been long and that it’s even made it hard for her to sleep.

“My mother-in-law, the first resident here, told me she used to receive text messages and emails from the Public Defenders’ Office about the eviction order. She appealed, and then everyone else [other residents] joined her, but there has never been a final decision or any kind of agreement. After she passed, my partner and I were left to face this situation ourselves. It’s been distressing because we have nowhere else to go. We have a daughter with special needs, and it’s very hard to live with this uncertainty. You can never relax or sleep properly. We’re always thinking about it. It’s really difficult. I never imagined going through a situation like this, suddenly being without a home. It’s truly unbearable. My children grew up in this house. All we want is permission to keep living here.” — Ana Maria Goulart

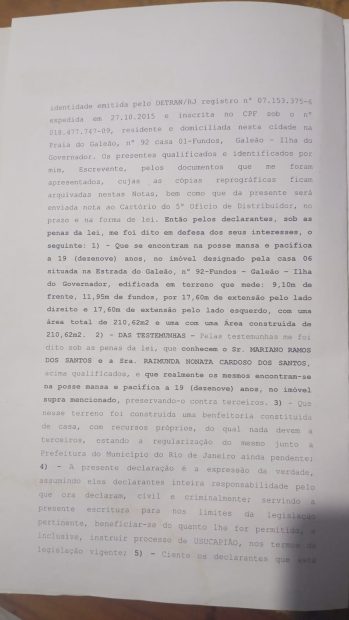

Although Estrada do Galeão No. 92 has not yet experienced any forced evictions, it is now also at risk. The land where the community is currently established was donated in the 1990s by a former Air Force colonel from Ilha do Governador to an employee who performed repair work at the site. Since the plot of land was so large, the employee—and new owner—granted small portions to other people living in vulnerable situations. However, according to Jeferson Almeida,* a resident of Estrada do Galeão No. 92, the respite lasted only six years. In 2003, they received their first eviction notice.

Years later, in 2016, the new residents filed a request with the notary office to register the land. However, although they obtained a notarized declaration, the eviction notices never stopped. To date, ten notices have been issued to this community.

“They [court officers] came here to talk to my father and said we had to leave. At the time, my father sought help from the Public Defenders’ Office, and from then on, the lawsuits just kept pouring in. Every time a lawsuit came, he’d appeal, and that would be the end of it. In 2017, another one was filed, this time requesting the return of the land. They [the Air Force] evicted the residents from another area [the Maracajás community], located behind ours, and left the plots of land abandoned. Some houses have been empty and falling apart for seven to ten years.” — Jeferson Almeida

Almeida said that, in his opinion, the only possible explanation for this persistent push for removal is the plan to build a waterway terminal that would turn the area into part of Rio de Janeiro’s tourist infrastructure. From this terminal, ferries would connect Galeão Airport to Santos Dumont Airport, across Guanabara Bay, in the city’s downtown area.

“They want to kick us out because they want to profit from the land. [They want to build] a ferry station here. The federal government and the Air Force want to take over land they never cared about, that was abandoned, to claim ownership and make money. There are houses that have been sealed off, with gates bricked up.” — Jeferson Almeida

The pressure has intensified over the past two years. After four meetings with COMAER, residents were offered no fair compensation or alternatives, nor was there any concern for proper relocation or fair and proportional indemnification.

‘Where Will We Go?’

Silvia Santos* opened up about the lack of respect and humanity shown toward residents.

“There are children here, elderly people, sick people, you know? All we want is for them to have some conscience, right? To understand that we are human beings. Where are our human rights, that we don’t seem to have? To them, we have none. We’re here fighting, everyone worried, with our heads in our hands, [asking ourselves: at the] end of the year, where will we go?” — Silvia Santos

Roberto Nascimento,* 43, a dispatch worker and resident of Estrada do Galeão No. 92, explained that there have not been any attempts at a peaceful agreement between the parties, and that the conditions imposed would put residents in an even more vulnerable situation.

“Everyone here earns a salary, works, has a job. The only asset we have is the house we live in. Either they let us stay, compensate us, or relocate each family to a suitable place. And don’t give us any of that social rent stuff, because that doesn’t work. They start out paying for a month, as I’ve heard, and then they stop. Plus, the amount isn’t enough—you start out paying rent, and then what about the rest? Electricity, water, all that? It’s the workers who end up suffering, leaving home in the morning not knowing if, when they return, their house will be locked up or broken into. If you look at the project… [the motivation for the forced evictions] it’s commercial… since they can invest billions [in this project], what would it cost them to compensate each resident here? Nothing.” — Roberto Nascimento

‘The Government Doesn’t Care About the People’

Luzia Alves,* 45, a hairdresser and resident of Estrada do Galeão 92, shared her concerns.

“Why did they let these 17 families build here in the first place? Just to do this injustice to us now? I really hope they find a solution to our situation so we do not end up like the other residents back there in Maracajás, who were evicted seven years ago. I still cry when I think about it. It traumatized me to see a woman over 90 years old in a wheelchair, [being forced out of her home] under the blazing sun. It was horrifying, there were all sorts of [armed] forces there to drag people out by force. They didn’t give those residents any other kind of home: that was that. I mean, [these people] have their homes, a safe house to sleep in, right? A place to come home to and see their families. And what about us? We have nothing. The truth is, no one really thinks about poor people. They don’t care about the poor.” — Luzia Alves

Conceição Batista,* 72, a retiree, spoke about the lack of dialogue and concern for residents, which makes resolving the issue even more difficult.

“It cannot be like last time, when they showed up with a truck, wanting to shove everyone inside like pigs and throw our furniture out. No one here has the money to buy new things. So they need to come up with a solution. What do they want? To create more problems for us? That’s why there are so many favelas in Rio de Janeiro, so much crime—that’s the reason. Because they, the government, don’t care about the people. No one here stole anything. Everyone worked really hard, and everything here is the result of each person’s sweat.” — Conceição Batista

Maria Augusta,* 53, homemaker, Rádio Sonda resident, emphasized the importance of obtaining support during this very delicate moment for the residents.

“We are seeking solutions in Brasília because we have not been able to achieve anything with the Air Force in Rio. Other parliamentarians have tried to negotiate an agreement with them, but we got nowhere and, now, even with the involvement of the Conflict Mediation Commission, we still haven’t found a solution. These families didn’t get here yesterday, they’ve lived here for many years. They give no explanation for why they want this area. There are plenty of abandoned barracks left unmaintained. If they don’t even take care of their own areas, why are they demanding our homes and leaving everything behind? If that’s the case, then they should compensate and relocate us. We have poor families here. These are working families with children. We want our right to housing. That’s what we want.” — Maria Augusta

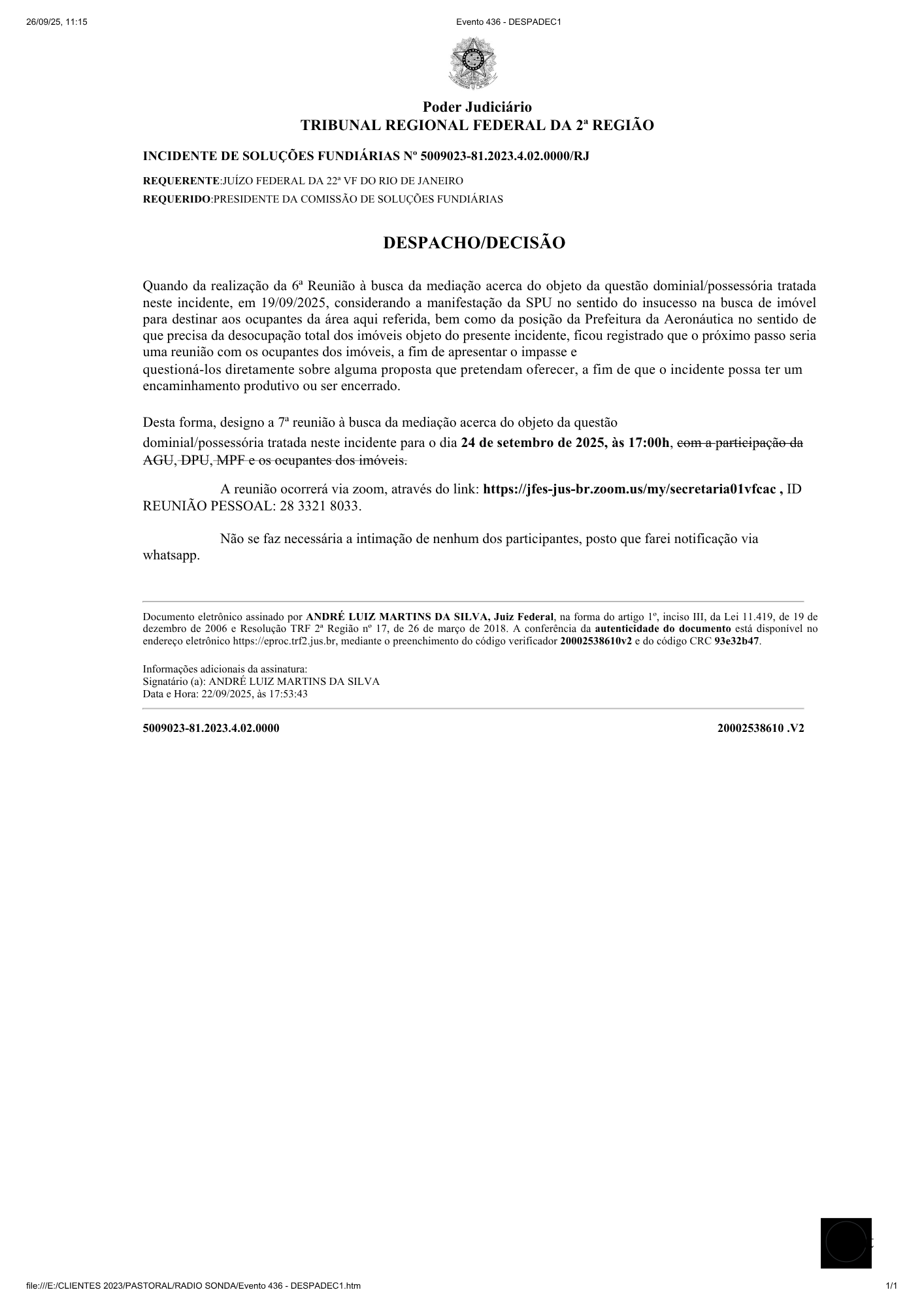

At the moment, the communities continue their struggle as they await the possibility of reaching an agreement with COMAER, in a session of the Land Affairs Commission at the Federal Regional Court of the 2nd Region, scheduled for October 15, 2025. Meanwhile, residents live in a constant state of anxiety, fearing their homes may be demolished—places where they built memories, raised families, and lived their lives—erased by the State’s inability to guarantee the right to housing for these three communities from Ilha do Governador.

Note: At the time of publication of this English version, RioOnWatch was informed that the forced eviction has been postponed by 90 days. Residents continue their fight for the right to remain.

*All names in this article have been changed to protect the safety of residents interviewed by RioOnWatch.