This is our latest article on the new coronavirus as it impacts Rio de Janeiro’s favelas and part of our partnership with The Rio Times. For the article as published in The Rio Times click here.

On June 15, the state of Rio de Janeiro exceeded 80,000 confirmed Covid-19 cases and nearly 8,000 deaths, according to the State Health Secretariat. 5,090 of these deaths occurred within the state’s capital city, Rio de Janeiro.

Due to widespread underreporting of the disease, especially in the city’s favelas, the number is undoubtedly much higher. A survey conducted by Voz das Comunidades lists 15 areas monitored by the favela-based newspaper through publicly-available data. According to that conservative account, 1,832 residents have been infected with 397 cumulative deaths. Rio de Janeiro has 1018 favelas, according to the city’s Pereira Passos research institute. Very few are being monitored.

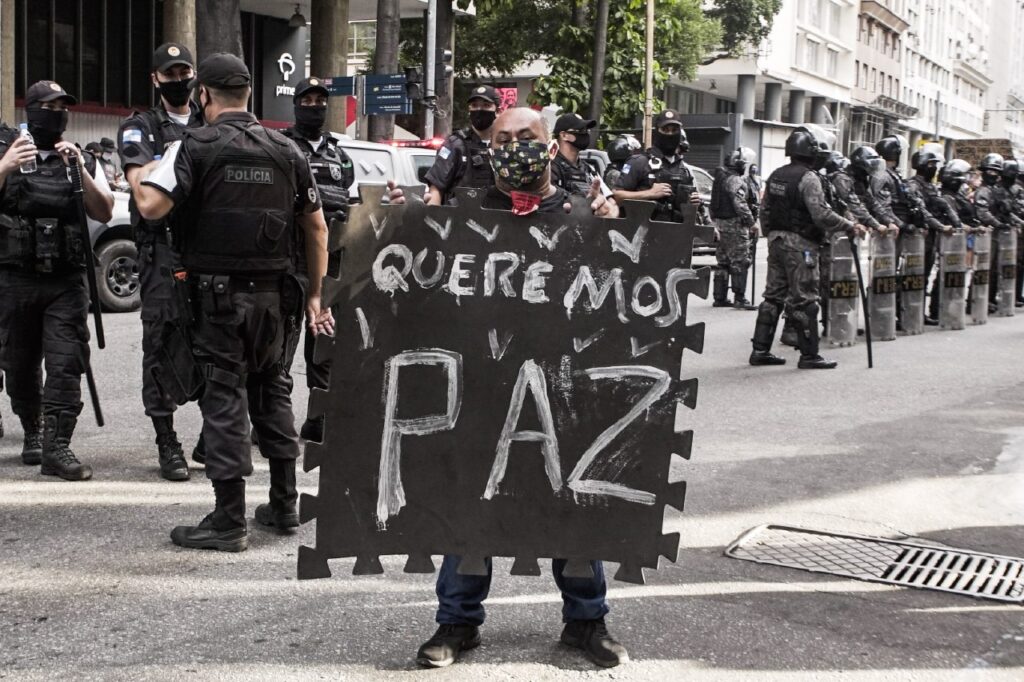

Despite facing this scenario of mourning and infection by the virus, black, poor, favela and peripheral residents of Rio occupied the streets for two consecutive Sundays to protest against racism. On May 31, protestors gathered in front of the Palácio da Guanabara, the official residence of the governor, and shouted “Black Lives Matter!” and “Favela Lives Matter!”

On June 7, another antiracist protest organized by the Favela na Luta Movement—with the participation of associations from the peripheries and the black community—again gathered nearly a thousand people to march down the city’s central Avenida Presidente Vargas. But, why risk infection from coronavirus at physical, in-person protests?

Voices of favela residents heard by RioOnWatch were emphatic. Protestors were forced to the streets by outrage, but also as part of a combination of factors: social vulnerability exacerbated by the public health and economic crises caused by the new coronavirus, in addition to unrelenting police violence in the favelas, even amid the pandemic.

Renata Trajano of Coletivo Papo Reto and the Complexo do Alemão Crisis Cabinet said there is no such thing as “the favela not going to the streets” when “the only certainty is death. We went to the streets because if you don’t knock the system down, it ends up knocking you down.” Rio favelas have experienced an increase, not a decrease, in police violence during the pandemic.

In April, police operations increased by 27.9%, according to a report by the Security Observatories Network. The number of deaths due to intervention by State agents increased by 43% as compared to the same period in 2019, leaving 177 dead in a single month, according to the Public Safety Institute.

Brazil, and in particular Rio de Janeiro, has one of the most lethal police forces in the world. It is within this context of choosing between death by hunger, the virus, or police rifles, that the favelas face an impasse amid the Covid-19 pandemic. In this equation of fear, pain, and mourning, not occupying the streets due to the risk of infection is not an option, said community leaders.

“What’s important today is to stay alive so that my favela can have rice and beans, because the State is not here, as usual,” explained Trajano. “The only thing that reaches the favela [coming] from the government is police firepower. If we’re not out on the streets telling them to stop killing us, we’ll be carting away bodies every day! Does the pandemic factor in my thinking? It does, but I have to think about how I’m going to survive first, about staying alive… so that afterward I can say I survived the pandemic.”

A mother and head of household, a black woman, a human rights activist, and a resident of Complexo do Alemão, in the North Zone, Trajano feels that “being on the frontline of the fight against Covid-19” is gratifying but also “extremely painful.”

Trajano leaves her house every day in order to register families for basic food stuffs donated by companies and civil society to the Complexo do Alemão Crisis Cabinet. “We have a State that tells us to stay at home, but doesn’t provide any assistance. And most of my favela is comprised of black women who are heads of households. The State is doing nothing… and still asks us to carry on at home while getting shot and killed. It is collective negligence.”

On June 9, two days after participating in the antiracism protest in Rio, Trajano was stopped at a police checkpoint just as she was on her way to distribute food baskets in Morro dos Mineiros, one of the favelas of Complexo do Alemão.

Estava com minha bolsa portanto minhas armas, máscaras, álcool, planilhas impressas e canetas, estavamos com a camisa do @gabinetealemao e devidamente equipados. Passei nossa localização pro restante da equipe que já estava no nosso ponto de encontro

— Nega Rê 🏴 (@RenataTrajano1) June 9, 2020

Estava visivelmente irritada com toda aquela situação, fuzis e pistolas apontados como se fôssemos criminosos. Nosso único crime sair de casa pra fazer o bem pra nossa gente. Depois de quase 20 minutos de revistas fomos liberados

— Nega Rê 🏴 (@RenataTrajano1) June 9, 2020

Heading out today for another day of food and hygiene kit distribution, I was stopped by the Military Police with pistols and rifles pointed at our heads. We waited for the order to step out of the car, and then the police’s order for everyone to “have their documents in their hands.”

I was carrying my purse and therefore my weapons: masks, hand sanitizer, printed spreadsheets, and pens. We were wearing the @gabinetealemao t-shirt and with the correct equipment. I sent our location to the rest of the team, already at our meeting point.

I was visibly irritated with the whole situation, rifles and pistols aimed at us as if we were criminals. Our only crime was leaving the house to do good for our people. After almost 20 minutes of them searching us, we were released.

Trajano said that surviving the government’s systemic racism doesn’t allow for physical isolation or social distancing in the day-to-day lives of favelas. “You can’t just come here and execute 13 people and then tell me there was a shootout, because all the dead were shot in the back, in the head, or were stabbed to death. We are on the streets because there is a buildup of outrage,” she declared. On May 15, State security forces killed 13 people in Complexo do Alemão, in an operation that lasted two hours.

The Favela’s Fight for Justice is Racial

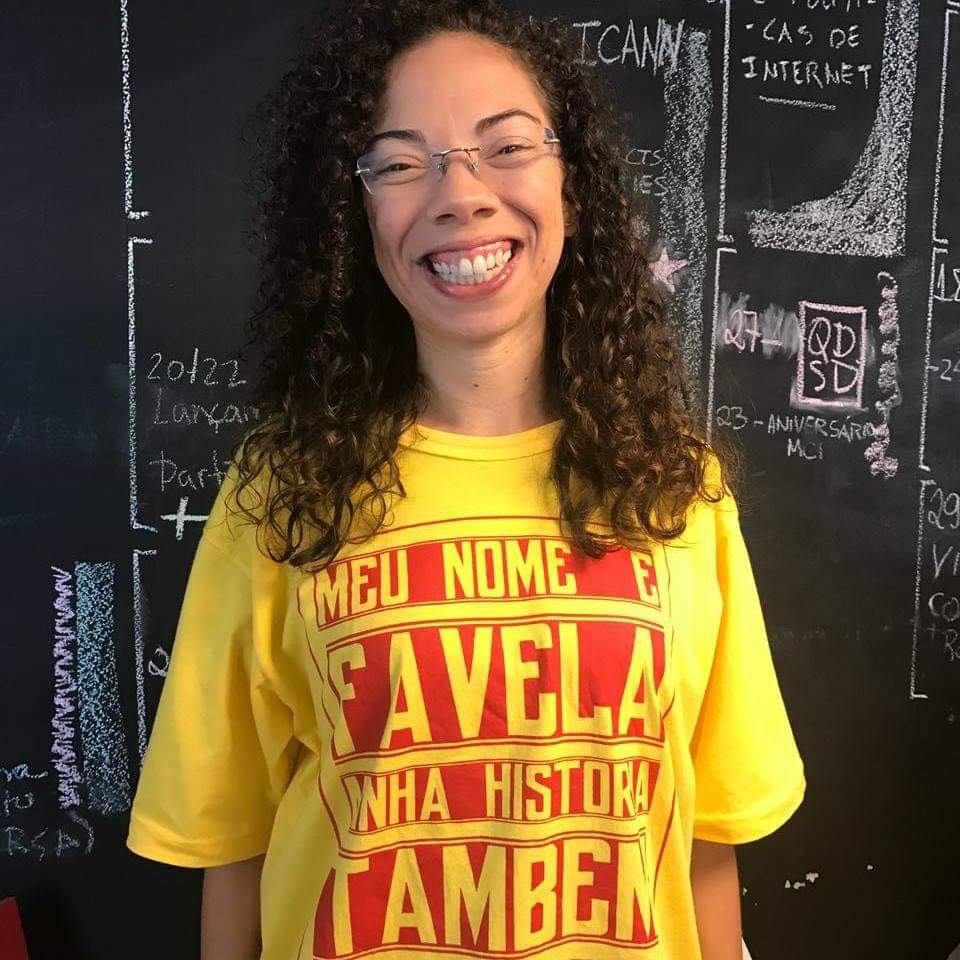

Gizele Martins, journalist and member of the Frente de Mobilização da Maré (Maré Mobilization Front), explained that the favela movement is fighting and protesting against racism, because the Covid-19 pandemic has shown just how little the government cares about the favela population. On the contrary, instead of looking after and providing assistance, a death sentence is handed to the favelas and peripheries in the form of a security policy.

“It’s our people who have died and have been most infected with the new coronavirus precisely because this population doesn’t have a choice: they must go to work, they must expose themselves, because otherwise, they go hungry. Their employers prefer that they work instead of protecting their lives at home,” Martins highlighted.

“Even so, the state government with this so-called ‘security’ policy has not stopped killing our people from shooting towers, from helicopters, from armored vehicles and other weapons of war. This is a policy of genocide: where there is a black body, the gunshots of this racist and fascist State, come to kill,” protested Martins.

She explained that movements combating Covid-19 in the favelas have not changed their campaign. The request made by leaders, collectives, community communicators, and residents continues to be that people follow the World Health Organization’s (WHO) recommendations: stay at home, if you can. At the antiracism protests, a committee from the organization, aside from instructing everyone to wear masks and use hand sanitizer, also took care to ensure that protestors kept 1-2 meters apart from each other.

The issue is that: “The police want to kill us! Our population has no medical assistance, no tests, no food, no gas, no supplies, no homes because there’s no money to pay rent. So we ask: How are we going to stay at home if we don’t have one anymore? How are we supposed to wear masks if there are people who don’t have money to buy food? We’re experiencing complete chaos in the favelas and the peripheries. Not going to the streets was not an option. We had to go,” said Martins.

Black Lives Matter Because Favela Lives Matter

The journalist’s declaration points to the State’s management of death, indicative of racism evident in the State’s necropolitics. According to an analysis by Professor Silvio Almeida, author of the book What Is Structural Racism?, the pandemic has made visible and revealed to all how racism organizes life in society. The favelas went to the streets, despite fear of infection, because they could no longer stand the lethal violence of the State compounded by the daily racism in the midst of the pandemic.

“The death rates have intensified even more. One life is not worth more than another. No one has to die, but they’re dying. These deaths are not in the wealthy buildings, they are mainly in the favelas, where there are black people,” said Naldinho Lourenço, a photographer and resident of Maré in the North Zone. He feels it’s unsustainable for the State to further increase the lack of structure and the inequalities in areas whose existence is already denied.

“Due to the lack of government action even in the face of the pandemic, the favela is creating survival strategies: distributing food baskets, masks, and water to people, things that are denied to the favela, because the only right that is given to us [by the State] is the rifle constantly aimed at us. We’re on the streets because we must be, because the biggest complicating factor in the favela’s struggle during the pandemic are these endless police operations,” complained Lourenço.

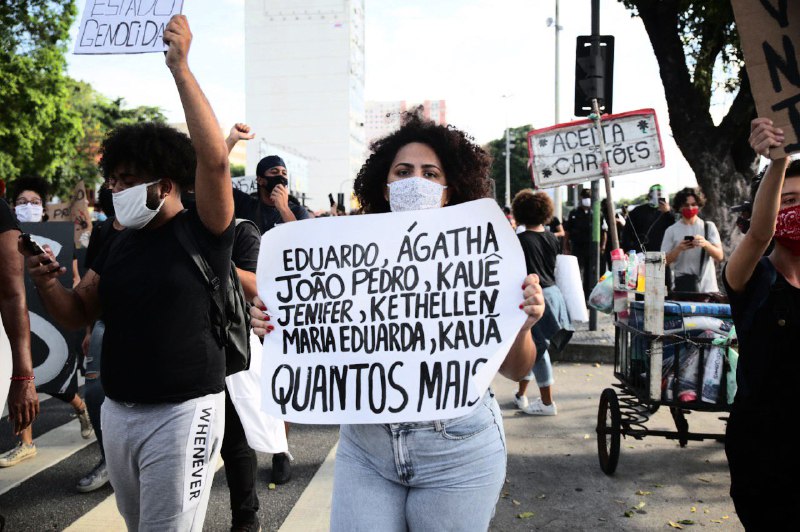

The pandemic created a chess game of survival that has left the black, poor residents of the favelas and peripheries with no choice. The first antiracism march in Rio de Janeiro took place after a series of cases of young black people being killed in police operations in the favelas, including: teenager João Pedro Pinto Matos, age 14, in Complexo do Salgueiro, São Gonçalo; the massacre in Complexo do Alemão that left 13 young people dead; the case of Rodrigo Cerqueira, killed during the distribution of basic food baskets in Morro da Providência; and the death of another young adult, João Vitor Gomes da Rocha, which occurred in a police shootout during another food basket distribution campaign in City of God.

“We decided to assemble this protest with all the security measures in mind, meeting the WHO’s recommendations and [ensuring it was] peaceful, because what we want is to externalize our indignation with the number of people murdered in the favelas by Covid-19 or by gunshots. During these past few weeks, we’ve seen many people die, even people who were delivering food to our people, delivering basic food baskets. We had to cry out! We had to say enough! And what else could we have done? We needed to be on the street, because the street is still a tool that creates more strength,” said Lourenço.

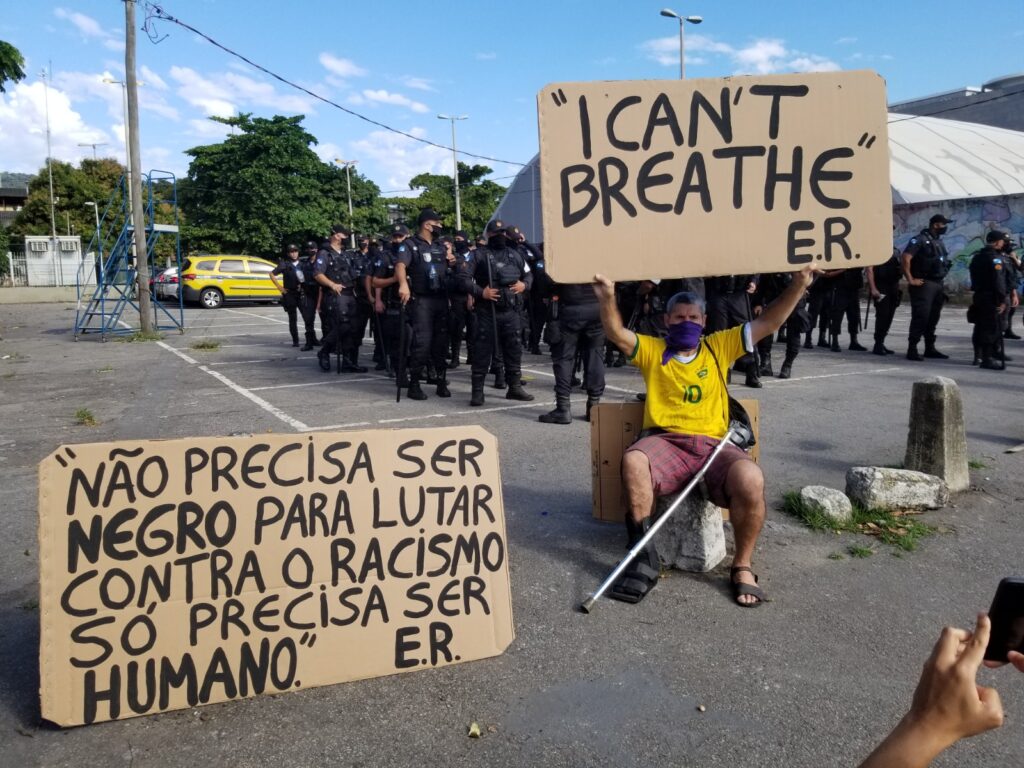

Mônica Cunha, coordinator and founder of Movimento Moleque, who lost her son to police violence, said that in Brazil, like in the United States, “black people also can’t breathe,” in reference to the murder of George Floyd. “I can’t breathe” were Floyd’s last words as he begged Minneapolis police officers for his life. His death caused the insurgence of a black uprising via the Black Lives Matter movement and antiracism protests, quickly spreading around the world.

A black woman and former domestic worker, Cunha joined the antiracism protests in Rio de Janeiro despite being part of the risk group due to her age and her high blood pressure. She has been participating since the first #BlackLivesMatter antiracism protest on May 31.

“The situation in the favelas and for black people because of the pandemic alone is total pandemonium in Rio. The case of George Floyd was just a catalyst, because the feeling here is the same: nobody in the favela can breathe because the State does not allow black people to grow and live,” she explained. Also a participant of the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence—her son was murdered by the police in 2006—she said that black women can’t bear to cry anymore.

“They’re killing our men regardless of their age,” protested Cunha. “The 5-year-olds like Miguel, who fell from the ninth floor because his black mother was unable to self-isolate at home and had to go to work; the 23-year-olds like the young people from Complexo do Alemão; the 18 and 19-year-olds like those killed while distributing food baskets; our elderly are dying at the hospital due to the shortage of ventilators; our teenagers like João Pedro are being killed at home. We went to the streets to scream because we want our black people alive! We talk about the youth, because we feel instinctively that our young people are those most often mowed down by police rifles, but generally speaking, black men are dying and black women are getting sick.”

Considered a griot by young people in favelas—a living manifestation of memories passed from generation to generation—she highlights that “The quilombo we want to rebuild doesn’t only need black women, but also black men, alive, and of all ages.”

On Social Media and in the Streets

Virtual manifestations and protests across social media, for these voices heard by RioOnWatch, are insufficient. Despite the visibility and mobilization promoted by networks such as Twitter, the space on the streets must not be abandoned. Social media and the streets need to unite to expand their impact.

“We tried. We held a virtual protest where we were able to mobilize the entire country, but it wasn’t enough. We were wearing gloves and masks and using hand sanitizer, trying to protect ourselves by staying home, but we were forced to fight for our lives outside our homes to try to save our lives inside our homes, because the bullets and Covid-19 kept coming! And this is why we’re in the streets shouting ‘Black Lives Matter!’”, Cunha emphasized.

Lourenço agrees. For him, the street is the stage for claiming rights and shining the spotlight on the importance of the struggle. “This is why we went, during the first protest, where the governor lives, or supposedly lives. We had to go there to send a message. To say that we were there, but that we don’t want to die. We live in the favela, but we don’t want to die, man. If the governor doesn’t listen to social media, we’ll go to his doorstep and shout it. That’s it!”